The internet’s favorite baker shows us how to improvise with confidence.

Claire Saffitz is a breakout video star of the home cooking internet, but deep down, she might not love video all that much. Perhaps this—a total lack of thirst and a humble indifference for the format—is the secret to her incredible rise from Bon Appétit Test Kitchen worker bee to the magazine’s senior food editor to the host of “Gourmet Makes,” the insanely popular series on said magazine’s YouTube channel that re-creates well-known grocery store items like Cadbury Creme Eggs, Cheetos, and Twizzlers in a home kitchen. The episodes, running 15-45 minutes, are mostly upbeat, straight-faced cooking demos, but with a wink at the (mostly male) food-science wonkery—and tired food TV in general. This endearing combination of cooking wit and mild snark, rolled up like a Little Debbie Honey Bun, has made Saffitz a star and a go-to voice for all things dessert.

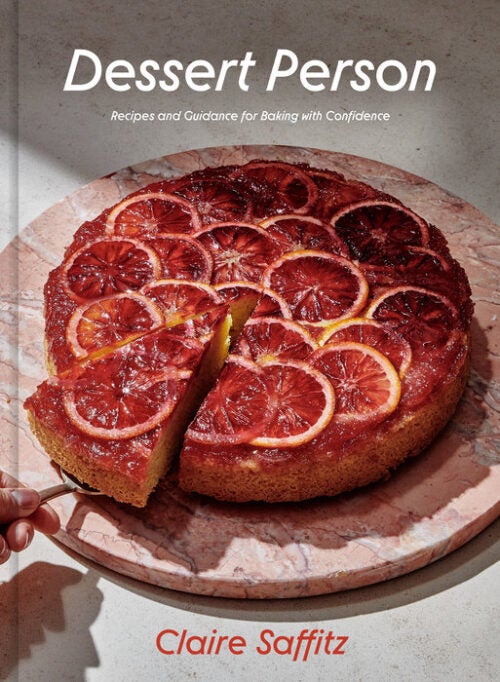

So it’s fitting that all of this has culminated in a debut cookbook like Dessert Person, which has been several years—and several pounds of sugar—in the making, and which syncs up more with Saffitz the scholar. Cookbooks are important to the Harvard and McGill–educated New Yorker, and in this long and lively conversation from mid-September, we talk about some of her favorites, as well as what drove her to perfect an English muffin recipe that she believes all of her nearly 1 million Instagram followers need to make. We talk about the turbulent events at Bon Appétit this summer, her own status at the publication, and why her next book will have a lot more gelatin in it.

You are about to put out a cookbook!

Yeah [laughs]. It’s very exciting. It’s been such a long time in the making, and then, all of a sudden, I wake up, and it’s like a month away. So, in some ways, it snuck up on me, which is crazy because I’ve been planning it for so long, but here we are. I’m very excited.

You put the work in, and I think it shows. Your readers will really appreciate that. And, I have to ask—there are a lot of baking books, and there are a lot of good baking books. It’s not like there are a lack of those. So, when you started writing, what were you setting out to do that was different?

This very much is a baking book. I would certainly characterize it that way. And the title is “Dessert Person,” but it is not literally a book of all desserts. I’m very quick to point out that there is a whole chapter on savory baking. So, when I signed the contract and I started to talk to my editor about what kind of book I was going to write, I knew it was going to be baking. And I really wanted the book to be, in many ways, about how creative and all-encompassing and even improvisational baking could be, because—and I say this in the introduction—I wanted this book to be an explicit defense of baking. Because, as a baker, I feel like I encounter anti-baking bias a lot from people who like food and like to cook but don’t like to bake, and who somehow find it to be a lesser art than cooking.

It’s like cooking gets to be improvisational and creative, and you have high heat, and you can kind of make it up as you go along, and baking is rigid and exacting and—of course there are rules; there are rules in baking, and you have to follow a certain process. But I really wanted the book to be about how abundant and beautiful and fun and expressive baking could be. So that was my mission statement, and part of putting the savory chapter in was explaining that baking can be dinner. Baking can be snacks. Baking can be, you know, not just dessert. Even though I love dessert, and I’m a dessert person, and that’s how I identify.

I fully agree with you when you say that people think savory is creative and baking is science—and I disagree with that sentiment, so thank you for saying that. But tell me—give me just an example of an improvisational baking recipe.

I mean, for me, inspiration comes from the market and from produce. And another similarity to me between baking and cooking is that baking is seasonal. You know, people are used to the idea of seasonal cooking, but baking isn’t just brownies and chocolate chip cookies—which, by the way, still have a season, too, because cocoa is a plant-based product. These things that we often think of as pantry ingredients, they’re still plant-based. I talk about that with flour. There’s still a seasonality to all baking ingredients, but particularly produce, and the desserts I like best are fruit-forward desserts. So, for me, improvisational baking is about going to the farmers’ market, seeing that “Oh my God, Italian plums are in season”—which they are right now; I was at the farmers’ market in my neighborhood this morning—

Which neighborhood are you in?

I’m on the Upper West Side. There’s one every Friday morning at 97th Street, so it’s a couple blocks away from me. I was there this morning, and I love this time of the year so much, and I saw a huge crate of gorgeous-looking Italian plums, and I bought a pound of them, and I took them home. Plums to me are enhanced when they’re baked. It not only intensifies the flavor, but it intensifies the tartness, which I love, because I love sour flavors. So, that’s what inspires me, and it’s like, “Okay, so I have some rolled oats at home, I have some butter, I always have cinnamon, I can bake a crumble.” So that’s what I mean by improvisational. I can be driven by the ingredient and by the time of year, and baking can allow that. It’s just that you have to sort of understand how to combine flavors and some foundational techniques, and that’s why I have that foundations chapter.

I encounter anti-baking bias a lot from people who like food and like to cook but don’t like to bake, and who somehow find it to be a lesser art than cooking.

You attended Harvard and studied humanities. How much was food in your world when you were attending university? Were you working in restaurants, were you baking, cooking? Or did that come later?

It came later. In my undergraduate years, food was not at the center of what I was doing at all. Certainly, writing was at the center of what I was doing, and that was the significant experience that I gained at that time in my life, that I benefit from now. And I’ve always loved to write. But at Harvard, it’s most common for students to live on campus all four years, and so there’s no kitchens, and no one is cooking—it’s unlike other undergraduate experiences where people live off-campus and they’re cooking for themselves and have a kitchen. We didn’t have that; we ate in the dining halls, you know, all four years.

I grew up in St. Louis, but around the same time that I started college, my parents moved to the Boston area. So I could still take a 20-minute car ride and go home to their house and cook when I wanted to, and I did that occasionally. But it was just not at all at the fore of what I was doing. That came really after college, when I did move into an apartment on my own, and I didn’t really know what I wanted to do. I was like, “How the hell am I going to use this humanities degree?”

Always the question with humanities.

Right. And it just became true that the one and only thing I wanted to do was cook.

And you studied French culinary history, is that correct?

That was post–culinary school. Around age 24, I had been out of college for a couple years, and I was like, “This cooking thing is not a phase. This is just all I want to do.” In hindsight, it was the culmination and the intersection of everything I love to do. Because I could incorporate writing—although, at that point, I wasn’t totally aware that food media was a thing.

Yeah. Thank God. You came in with an open mind.

I came from an educational background where, if you wanted to be a lawyer or work in finance or go to med school, there was lots of support. If you wanted to do something artistic, not so much. I decided that I should go to culinary school sooner rather than later, because I figured that the older I got, the harder it would be. And I decided, after looking at some programs in New York and seeing how incredibly expensive they were, on culinary school in Paris—because, you know, the movie Julie & Julia had come out, and I was so enraptured with this idea of living in France.

I started to explore schools in France, and I found a much less expensive, English-based international program at a school in Paris, so I moved to Paris for a year. And I had a job as a busser in a restaurant after high school, but I had never cooked professionally, and that program included a required externship in a restaurant—which was appealing to me. I was like, “I really feel like I should get some restaurant experience.” So I did my culinary program, which was about eight months, and four months in a restaurant. I did not enjoy working in a restaurant—I enjoyed the work itself, but I hated the pace of the schedule.

And there’s gotta be some element of machismo in the kitchen. Was there anything like that, that was really off-putting to you? Someone who’s very cultured and worldly, and you were just like “this is not fucking right”?

I mean, I had wonderful cooks that I worked with. I liked the people a lot, but what I really chafed against was the hierarchy. In France, you get that classical brigade system, with the hierarchy, and I really did not like that. And I also felt like I did not respond to the kind of feedback that was entrenched in that culture, which was negative feedback. It was like, I’m someone that is very type A—I’m very hard on myself, and I am my own worst critic—so it’s like, I don’t need someone else to yell at me if I mess up. I know when I messed up, you know? You’re just sort of irritating me at that point. And I hated the idea that I didn’t feel that I could be very analytical. I was just like a machine.

Yeah, they were like, “Do this, robot person.”

Yeah. Pick these herbs—and I also ended up doing all the pastry for that restaurant, so I felt like I did not sign up for this amount of responsibility. I was actually okay with being a machine in that amount of time, but then I realized that this was more than I had bargained for. I wouldn’t trade it for anything; I learned so much. But I was just like, “This isn’t for me.”

And so, while I was in culinary school, I was applying to graduate programs. And I knew I could study this thing called food history. I wasn’t quite sure what it was, and I got into a program at McGill, and I went there because there’s a professor there named Brian Cowan who does some really interesting cultural studies and intellectual history around food. I loved living in France, I was like, “I can study all this,” which was great—and then halfway through that program, I was like, “I love this, I love learning about this, I love reading old cookbooks, it’s so rewarding and intellectually stimulating,” but it was the opposite end of the spectrum from working at a restaurant. I needed something a little more in the middle, where I could cook and write and think.

Enter food media!

Right, exactly. I was like, “Oh my God! There’s food magazines, I wonder if I could work at one of those.”

Take me back to that first restaurant in Paris. What was the first dessert pastry that you got on the menu during your time there. Do you remember?

The restaurant was Spring, which has since closed. But it’s a Daniel Rose restaurant—

Yeah, of course! A very famous place, dang! And an American!

Yeah. An American in Paris doing classical French food. I was there, and the pastry chef working was sort of part-time, so she didn’t work service; she did a lot of pastry prep and kind of set everyone else up for dessert service in the evenings. And there were parts of her job that were a little redundant, and so I think she decided to leave, and then Daniel was sort of like, “You like pastry . . .” And that was very true, I had told him I really liked doing pastry—and he was like, “You’re gonna take over that prep role.”

And the desserts at Spring were very interesting. They were not at all composed. It was really a series of sweet bites; it was its own kind of service. It would be things like a mini pavlova with beautiful macerated strawberries and crème fleurette driven down from Normandy the day before with pure vanilla—just the absolute superlative ingredients, featured very beautifully, but in the least fussy way possible. It could be a little quenelle of olive oil ganache, with beautiful olive oil drizzled on it. Or there was this recipe that I had to make that I probably got wrong 50 percent of the time. It was an Alain Ducasse recipe for a toasted almond chocolate caramel. That would be minardies at the end of the meal. I was always doing these individual, very simple preparations and then putting them out as a series of courses.

Wow. What a crazy responsibility for a very well-regarded restaurant. You had the keys!

I would get there at 9:00 in the morning, start my prep, then I would work lunch service, and then I would clean up from lunch, do more prep in the afternoon, set up for dinner service, work dinner service. I would do what he called aperitif courses, the amuse. And then I would switch to dessert, and would run dessert service, and then go home at like 1 a.m.

Switching gears—and this is important; I want to know. We’ve written about this a lot, but can you just remind people about why it’s important to buy a $20 digital scale? Because I think people need to be continually reminded. Your recipes are probably better with a digital scale, right?

Yes, absolutely. I mean, I was very careful, and from the beginning, I had intended to provide, of course, volume measurements—because that’s how everyone works, and sometimes I still work that way. But to provide metric and standard measurements for every ingredient—that mattered, in a sense. Like, I don’t need to give [metric weight] for a teaspoon of vanilla extract, because a little more or a little less makes no difference. But for every functional ingredient, I thought it was so important. It is certainly an efficient and accurate way to work, and overall, it’s just much more seamless, especially for bread making. Anytime you’re really measuring flour for anything, weighing it is so much better—and it’s amazing to see the variations in weight by volume; like, my cup of flour is always 130 grams, for the most part. But it could be 25 percent more or less, depending.

Yeah, people are packing things down like crazy; it’s just a natural tendency.

Yes. I think people are scooping flour in a measuring cup inside of the bag the flour comes in, which is just going to lead you to a very, very dense cup of flour. And so, in the book, I talk about how you should bring the flour home, put it into a container with a tight-fitting lid, scoop it into the cup, and then level it. All of these things really matter, and so that’s what I mean when I say that baking has rules and principles that you have to follow, but other than that, it’s not that scary. You just kind of have to know these things. And using a scale is a big part of that. It’s just to set yourself up for success.

Yeah, and they’re not expensive. They’re very, very affordable.

Right.

What was your biggest recipe conquest in the book? The recipe you set out to articulate, and it just did not work several times. The thing that you just felt like, at the end of it, we dialed it in, but it was a war getting there.

I mean, [my editor] Raquel was incredibly—I don’t want to say “permissive,” because that’s the wrong connotation. But she gave me incredible freedom to write the book that I wanted to write, and I got my first physical copy in the mail a week ago, and I was looking at it, having not seen it now for several months, and I was like, “Wow—I really wrote the book I wanted to write.” It felt like there was nothing mediated between what I set out to do and what the final product was. And that’s a big reflection of Raquel and her editing. But there were several recipes that she encouraged me to cut. And she was 100 percent right about it. I had a lot of much more savory recipes that she was like, “I just don’t quite think these go.” I had a lamb pot pie with olive oil pastry, and I had a sort of braised chicken under biscuits that was like a chicken pot pie. I ended up cutting things that were sort of free-standing recipes and that didn’t, to me, seem to fit in this world that was “Dessert Person.”

And I want to ask you about the English muffins. Raquel told me that was probably the one recipe that you worked on [the most]. She said that you were very, very stoked about doing English muffins. So, for me, I’m like, Bays makes some pretty good English muffins! I’m into industrial English muffins, so I’m not necessarily inclined to make them myself. But tell me why I want to make yours, because it makes sense that you should probably make English muffins.

Yes. So, I’m with you—a Thomas’ English muffin is a pretty tasty thing.

Yeah, it’s a better brand than Bays. I prefer Thomas’ as well.

Okay. But after you make homemade English muffins, you are going to open up a pack of Thomas’ English muffins, and you’re going to smell kind of a funky smell; it’s going to smell a little bit off, a little bit chemical, and then you’re going to realize that the fresh version of this thing is ten times better. It is hard to convince people that they should be making they own English muffin when there is a perfectly serviceable option that comes out of a bag. But I hope that people find recipes like that to be just sort of a fun project—and, actually, that might be the one recipe in the book that is not technically baked. It is griddled on a stovetop.

Oh, that makes sense! Some people don’t want to turn on their ovens, you know? For a variety of reasons.

Right, right. And I had previously done an English muffin recipe at Bon Appétit that was good, but I was like, “These can be better, and I can get more nooks and crannies.” So that was a recipe that I just had so much fun working on. I could kind of pull in knowledge from other recipes, it was like, “I know that in order to get that really open, whole structure; to get those nooks and crannies, you want a wetter dough.” So it was almost like I was moving that recipe further down the spectrum toward crumpets, which is really a batter, and I came up with what I think is a cool, relatively easy technique for really impressive English muffins that come out miraculously well, and that look eerily like the stuff out of the package.

Yeah, and that’s the key, because I think if you don’t get that right look, it’s like, “Okay, this is not an English muffin.” Those crevices inside are super important.

Yeah. I think it’s one of those things where it’s like, “Oh, I didn’t even know you could make this.” But they’re just really fun, you know? So I do hope people try them.

What’s book two?

I told Raquel I would have a table of contents to her like two months ago, you know? It’s been a weird summer, but book two is going to be, I think, the inverse of the first book. I’m really thinking of it as book two of a set of two, I guess. So, book one is all baking but not all dessert. Book two is going to be all dessert but not all baking. The first book has my favorite kinds of desserts, but it also totally ignores huge categories of other desserts that I still love, like frozen desserts, chilled desserts, desserts that are made on the stovetop. The second book is going to focus on the core concept of simplicity. Because book number one has some simple recipes, but it has some really complicated recipes, too.

Will Jell-O make an appearance? I know it’s making a comeback, as some people say.

Yeah! There are some kinds of gelled or jelly desserts that I really like, but it’s going to be less in the vein of 1970s Americana, and more in the vein of Taiwanese jelly kind of things.

Yeah, good. I appreciate that you’re not totally leaning into that trend.

It’s more like panna cottas and puddings and mousses, and stuff like that—which sounds complicated, and it can be, but it can also be so simple.

Do you have a savory book in you, too? Are you interested in that kind of world as well? I mean, not just as a diner, but as an educator and author.

Yeah. I mean, absolutely, and I look at myself first and foremost as a baker, but that does not define me. For years and years and years, I primarily did savory recipe development at Bon Appétit, and it’s like, I don’t just love sweets, I love all food. I just have a particular affinity for sweets.

Who do you look up to in pastry? Who are some of the industry members you really admire?

Many. I have long idolized Claudia Fleming, and her book is just such a north star for me in my career. Her style really embodies what I aspire to as a developer. There’s a real soulful quality to her cooking and her recipes. And same with Lindsey Shere and the whole history of Chez Panisse desserts; that book is so formative to me. Same ideas—it’s so driven by the seasons, and it’s rooted in a kind of European sensibility, but it’s also very American. And it isn’t limited by that. So those are two major ones. I’m looking over here at my cookbooks . . .

Your stack!

What else? Oh, and then there’s lots of bread bakers who really—I’m a bread baker hobbyist, but not by profession, so I’m a good home bread baker, but the pros are doing things that I can’t even imagine from my kitchen. People like Richard Hart, who is doing the most incredible-looking pastry and bread at Hart Bageri. The titans of the industry, I think.

And in terms of Bon Appétit stuff, have you met the new editor in chief, Dawn Davis, and are you involved in BA stuff right now? And I know you said it’s been an interesting summer; going forward, a lot of folks have left for various reasons. What’s your role there?

The summer’s been very challenging, but I think it’s been very necessary. And I have a lot of hope for the future of the brand. I’ve never met Dawn—a friend of mine is a former colleague of hers, and I’ve heard from other people in the industry that she is phenomenal. And I sincerely hope, on the editorial side, that I get to work with her and Sonia Chopra, who is a recent hire there. I’ve spoken to her a couple times. I don’t have a formal relationship with Condé Nast, neither with video nor with editorial. My video contract ended this past May. [Note: See Claire’s Instagram post from October 7, after this interview was conducted, that addresses her relationship with Condé Nast and Bon Appétit.] I’m taking some time right now to figure out what I want to do going forward, and I have the book coming out, and I’m starting the second book—and video was never for me and never my raison d’être in food.

You’re great at it, and I hope you do more of it. I mean it! You’re really great.

Thank you! I’ve found video can be really fun, which is something I discovered by doing it, and it also can afford me the opportunity to do the kinds of things that I love to do, like continue to write. I think that there are many reasons to be very hopeful for the future of the brand; I think having new leadership come in is going to be huge, and I’m really excited to see what kind of changes are made. And I do hope to continue some kind of relationship with the magazine, and with the brand, because I have a lot of loyalty toward it; that’s where I came up, and I think that this past summer pointed out some extremely salient and important flaws, and weaknesses, and serious shortcomings. And I do think they’re being addressed in important ways, and I feel like I’m a little bit in the same position as readers—as a longtime fan of the brand, I want to see that change. So I’m really in a wait-and-see kind of place.

Well, you have a lot of fans, and they want you to do more of your video series. They really do. But you’re saying maybe not, because you’ve got a lot of other things going on, and you clearly are an academic at heart, an instructor at heart, which I respect; I admire that you do both.

Thanks. Yeah, I think going forward, I would look at video as an opportunity to do more of those things that I really like, like the research and the learning. And video is a vehicle for that, so that’s the extent to which I would pursue it in the future, and that’s really how I want to orient myself in that space. Gourmet Makes is so fun, and I love doing it, because I love the crew, and the environment was so fun, but I never woke up in the morning being like, “I can’t wait to reverse engineer Skittles.”

I mean, what about Rolos?

For me, video is a great means to have an incredible opportunity to learn, because I always look at my job as an editor as being a translator—to take professional knowledge from chefs and other food professionals and translate it for a popular audience. And that’s what I want to keep doing; I think I’m always going to think like an editor in that way.

Democratizing food is really important to me, personally, and you’ve done that with your series. Because snobbery is the death of food media. And, along with many other things, snobbery is one of the worst parts.

Absolutely. And I hope that one of the things people saw in the Bon Appétit video was that everybody in the kitchen has their opinion, and likes what they like, and we kind of squabble over it, but I like to think that we’re not snobs. We’re opinionated, but I love Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups. There’s just no place for snobbery, I think.

I agree. And are you a pumpkin, tree, or egg person—for seasonal Reese’s?

None of the above! Classic only!

Classic only! Okay. We’re entering the pumpkin season, which I think is the best, personally.

I truly didn’t even know that was a thing.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

FOUR RECIPES WE LOVE FROM DESSERT PERSON

Flourless Chocolate Wave Cake

Claire openly admits to not really loving the overpowering rich and cloying nature of this popular cake, but this light version—which is also dairy-free—is her flourless magnum opus.

Apple and Concord Grape Crumble Pie

This pie is pure fall and early winter. It’s a unique flavor combination and a great way to use up the apples and grapes from the farmers’ market. The buckwheat crumble on top is a nice upgrade.

Buckwheat Blueberry Pancake

While the book is titled “Dessert Person,” the definition of dessert stretches beyond the classic cakes, pies, and cookies. This is a hearty pancake that the author calls “pancake adjacent.” The texture isn’t fluffy but rich and custardy, similar to the French clafoutis.

Classic English Muffins

Surprise! You can make your own English muffins. So, okay, this isn’t a classic dessert, but it’s a recipe the author worked on for months, and we really believe that there is nothing like a homemade version of the package of Thomas’ you have in your fridge.

MORE BOOKS TO BUY, READ, AND COOK FROM

Last week we talked to Yotam Ottolenghi and Ixta Belfrage about their newest vegetable-centric book, Ottolenghi Flavor.

In Coconut & Sambal, Lara Lee invites us into the Indonesian kitchen and teaches us that there’s a whole world of sambals out there.

In The Flavor Equation, Nik Sharma explains some of the science behind flavor, and why factors like memory and aroma affect the way we experience food. Check out some of his previous writing for TASTE here.

Martha Stewart knows her cakes.

Chaat, by Maneet Chauhan, proves that chaat is much more than just a snack.