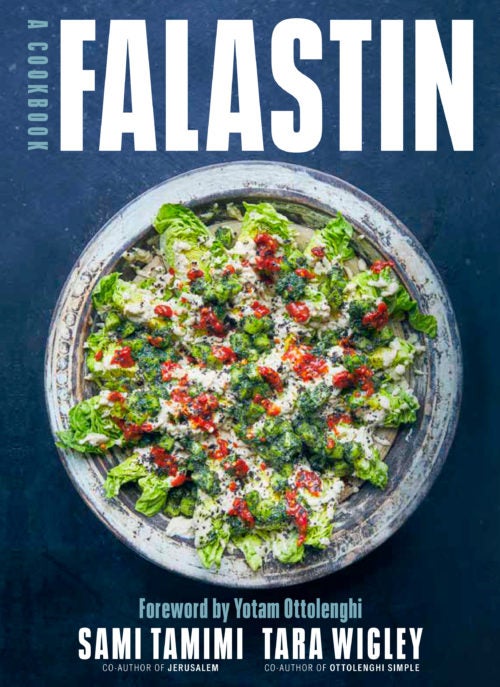

A new book, Falastin, brings one of the world’s great cooking traditions into focus through smartly reported essays, documentary photography, and 120 recipes.

When Sami Tamimi was coauthoring the cookbook Jerusalem with his creative partner Yotam Ottolenghi over a decade ago, a follow-up was already in the back of his head. “The success took everybody by surprise,” Tamimi says, smiling over Zoom from his London apartment. “We didn’t expect it to be this huge.” Jerusalem would end up an international best seller and help transform the way home cooks viewed the foods of a converging Muslim, Jewish, and Christian population in the holy city, ushering in the rise of now-common ingredients like za’atar, tahini, and pomegranate molasses in mainstream food culture. As the years passed, though, Tamini stayed busy building the Ottolenghi business—opening delis and working on other projects—and the idea remained stuck on the back burner.

Eventually, the time arrived and Tamimi teamed up with Tara Wigley, a trusted Ottolenghi recipe developer for over a decade, and it was agreed that the duo would travel to Palestinian communities, during several visits, to meet with local cooks, farmers, distant family members, and all kinds of restaurant cooks. The result is Falastin, a remarkable collection of essays and 120 recipes published this week.

With a population of over 130,000, Nablus is one of Palestine’s largest cities.

The trips—more than half a dozen in total—would form the heart of the text, which is broken into recipes (exacting and suited for the home kitchen) and reported essays featuring a group of yogurt makers in Bethlehem, plates of pastry at Majdi Abu Hamidi’s Al-Aqsa bakery in Nablus, or a meditation on hawader—meaning “ready to eat”—and the practical and poetic uses of freezers. “Time kind of stopped when Sami had these moments with the dishes he grew up with, the shish barak or the knafeh,” recalls Wigley, who anchored the book’s writing and recipe development and seems like a pretty great hang.

These smartly reported stories are as inviting as the recipes, like the one for winter tabbouleh with blood orange dressing or peas, spinach, and za’atar fritters. “It was hustling and bustling and the people selling falafels and butchering the meat—it all brought me back home to the home I remembered,” Tamimi says of his reporting trip to Nablus in the northern West Bank. I spoke with Tamimi about his journey a few weeks ago about transporting readers to a place more people should visit in person and capturing one of the world’s great, and lesser-known, culinary traditions.

How did your many reporting trips inform the recipes and the essays?

The point of the trips was to meet people and be inspired. We decided from the beginning that it wasn’t going to be my story, but many stories. We kept meeting people and meeting people, and eventually had to make a selection of who we would profile and which recipes would have photos and not. It was difficult to pick with our overall goal of illustrating what is modern Palestine.

You travel throughout the West Bank and beyond, and it feels like you are capturing many sides of this complex story.

It used to be a bigger place, and now it is shrinking with time for a lot of reasons. And each region had its own specialty and cuisine, from a specific cheesemaker to a lady making this specific type of couscous by hand to a specific tahini guy. But because of the smaller size, a lot of it is overlapping. I’ll say this: When we visited with the photographer, people were really excited to pose for the camera and talk to us.

Why should people visit cities like Nablus and Nazareth, where you write about chef Daher Zeidani and his salsiccia, long beef and pork sausages soaked in white wine and spices? (People should visit.)

That is the hope and certainly what we wanted to achieve from all of these profiles. You hear a lot of bad press around the situation, and people are scared to visit. But once you do go, it’s really great. There are people who organize food tours, which is a really positive thing, and we simply want people to eat the food.

You write about the book treading a fine line between paying heed to the region’s relationship with Israel and making the book a celebration of the food and people. How did you strike this balance?

This was something we were quite cautious with. Words are loaded when you talk about this part of the world. You have to be careful because at the end of the day, it’s a cookery book with recipes, but with real stories about real people. We didn’t make up any of that. Also, I think people will always choose a side: if they want to see it as a political book or a cookery book. Some people will probably have a problem with it, but most people have absolutely fallen in love with it.

The idea of hawader is really interesting, keeping around “ready to eat” foods in large freezers that might not be in season. How does that work exactly?

Palestinians love to eat seasonal foods, and when certain foods come into season, there are large celebrations—often with extra food that can be frozen and then eaten later to continue the celebration. This is also why drying and preserving are also very common. When you visit a Palestinian home, they don’t just offer you a salad and a meat. They want to make you feel so welcome that they want to offer you the best they have. In an hour there will be a large feast ready, with all these foods from the freezer.

What makes your take on lemon chicken with za’atar so special? This is such a popular dish you see in magazines and on websites. How do you do yours? What is the Sami Tamimi stamp?

It’s a few ingredients and just delivers on all the levels. There’s a really good amount of za’atar, and raw garlic that has been cooking slowly, so it’s sweet. And lots of lemon. You can make it the night before as well.

You eloquently note how there is no “p” in the Arabic language. Did you have to fight your publisher to make Falastin the title?

It was that way from the beginning, from the pitch, and the publisher agreed. When we started testing recipes in the kitchen, there was some debate if people would get it. People get it.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

RECIPES TO TRY FROM FALASTIN

Peas, spinach, za’atar, and preserved lemon fritters

What an amazing combination of flavors for a quick-fry fritter snack or a larger main course.

Bulgar mejadra

According to Tamimi, for many Arabs and Palestinians, mejadra is the ultimate comfort food. Always with crispy onions.

Pulled lamb shawarma sandwiches

Have you thought about slow-cooking a lamb shoulder today? You should.

Knafeh

According to the authors, knafeh—and philo dough pastry made with salty cheese—is a national institution and a particular favorite in Nablus.

MORE COOKBOOKS TO READ, BUY, AND COOK FROM

Everybody should buy Easy Eatings: The Book for Kids Whose Parents Don’t Cook (even if you aren’t a kid, don’t have kids, or don’t need a cookbook). Makes a great gift. All profits will be donated to Save the Children, a charity providing food to children impacted by the COVID-19 outbreak.

Troop 6000 details the remarkable story of the first Girl Scout troop, founded for and by girls living in a shelter in Queens, New York.

Rebel Chef: In Search of What Matters is a new memoir from San Francisco chef Dominique Crenn.

We recently caught up with Andrew Chau and Bin Chen, the authors of The Boba Book, for a cool interview about their current business model during Covid-19, and the boba (and non-boba) recipes you should be making.

The World Eats Here brings home recipes and stories of the immigrant vendor-chefs of NYC’s most popular night market in Queens.