Remembering New York City restaurants of the 1980s through the dishes of the times.

I just watched American Psycho the other night and could not get that Phil Collins voice out of my head. He is one of my favorite singers of all time, and, indeed, Invisible Touch was Genesis’s undisputed masterpiece. But my biggest takeaway from that movie, and the Bret Easton Ellis book it’s based on, is always going to be Dorsia. In late-1980s New York, Dorsia is the city’s hottest restaurant. “Dorsia. Great sea urchin ceviche,” goes the line in a movie with many memorable food lines.

In the novel, the restaurant serves as a key backdrop for the author’s dark satire of an age of conspicuous consumption, including the swiftly emerging foodie movement. In 1985, restaurant reservations served as a new form of cultural currency, not unlike a Rolex Explorer or Ferrari 288 GTO. At the time of the book’s publication (1991), New York City was entering the dawn of the celebrity-chef age, a few short years before People named David Bouley as one of the 50 Most Beautiful People (1994) and the launch of the Food Network (1993). But Dorsia is pure 1980s, when chefs were more anonymous and partied nearly as hard as their customers winding down an 80-hour week at Solly.

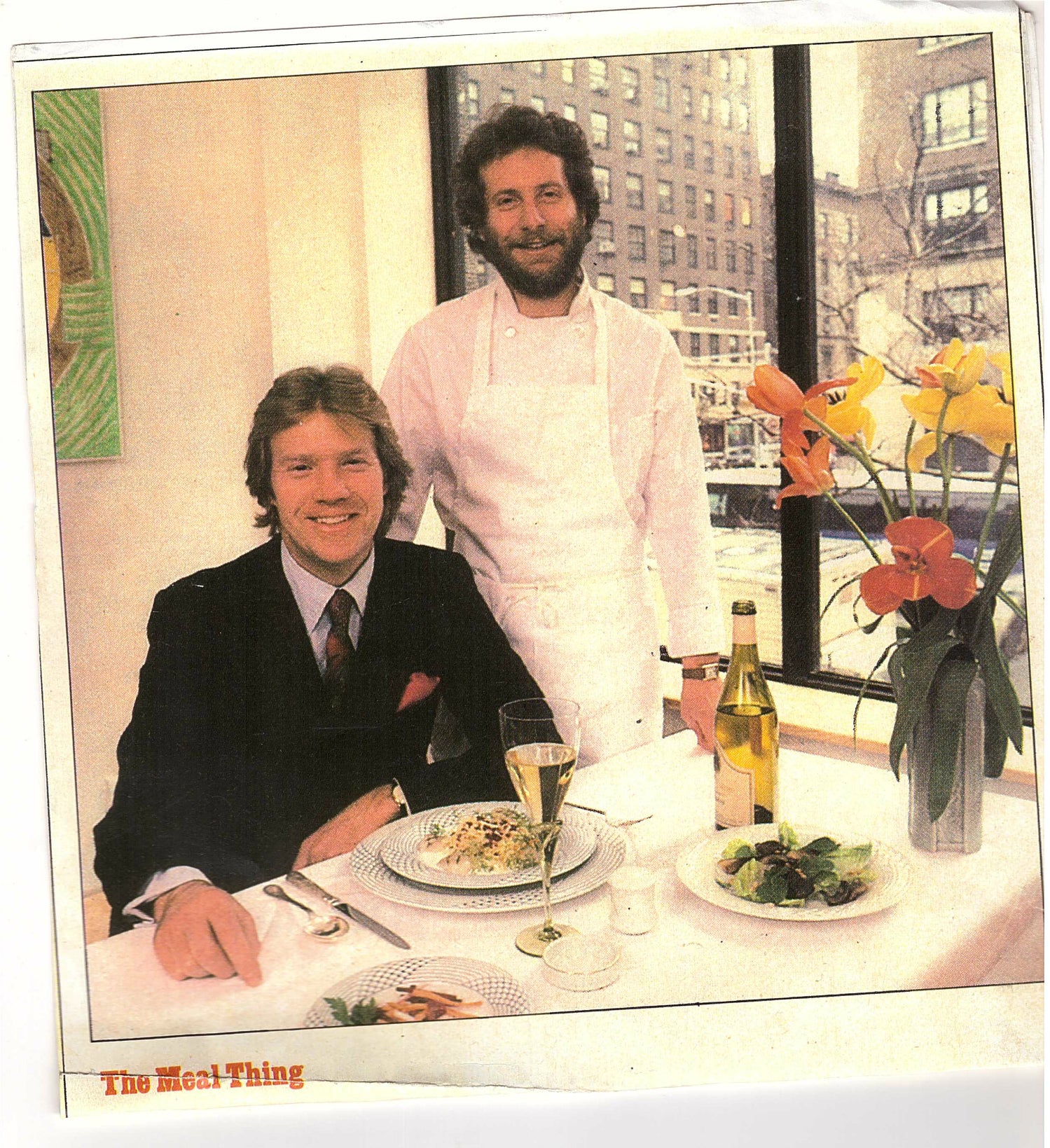

Jonathan Waxman (far left), Ralph Tingle (right), and Ed Fertig (far right) with staff in the kitchen at Jams.

But I was born in a small Midwestern town in 1980! What was I to know about this universe? For a little background, I called chef Jonathan Waxman. While Waxman was born in Berkeley in 1950 and is considered one of the elder statesmen of California Cuisine—lighter vegetable cooking with inspiration from Italy and Mexico—he brought his style east in 1984 to open Jams Restaurant on East 79th street, which critic Gael Greene colorfully detailed in the September 24, 1984, issue of New York:

“Jams opened noisily. Highly touted. A Best Bet. Not an acoustic tile anywhere. Those gastronomic virtuosos who can divine the scent of success even before Con Ed hooks up the gas were huddled at Jams’ tables from day one, screaming to be heard above their own din, delighting in the exquisite salads and mesquite-infused flesh of fish and bird…choking in the runaway smoke of the grill.”

Sounds a little familiar. “That’s not one of my favorite films,” says Waxman, laughing, when I phone him to talk about the era of Dorsia. I ask if he recalls having the mergers and acquisitions guys in the place, dining with models and bottles of Château Pétrus. “I had this woman working the front who called herself the most high-powered host in New York,” he recalls with a laugh. “Mike Nichols proposed to his wife at Jams. Andy Warhol used to come uptown for Jams. It was a hectic and amazing time. You would have loved it.”

Indeed, I would have loved it. But in the year 2018, and until very recently, all I’ve got are some hazy chef stories and old magazine articles. But that was before Andrew Friedman, a journalist and collaborator on over 20 cookbooks, published his latest work, Chefs, Drugs and Rock & Roll: How Food Lovers, Free Spirits, Misfits and Wanderers Created a New American Profession. As the title suggests, the book—colorful, with bursts of clarity from a pretty opaque time—features reporting from over 200 interviews and describes the rise of restaurants like New York’s Le Cirque, the Quilted Giraffe, Chanterelle, Ma Maison in Los Angeles, Chez Panisse in the Bay Area, and of course Jams.

“Jams was a perfect storm of a cutting-edge style of American food—so-called California Cuisine—a white-hot American chef migrating from the West Coast, and a new design aesthetic,” says Friedman. “Its arrival in New York City arguably marked the moment when the different cultures and chef communities of the two coasts first cross-pollinated.”

This convergence of styles, and increased media attention on restaurant chefs, carried over into home cooking—with pesto and pasta salad going from restaurant menus to kitchens around the country. Here’s a brief look at some of the dishes the era inspired.

The urban pasta salad

In 1982, six words changed the course of culinary history. “The pasta salad is here to stay,” wrote New York Times columnist Florence Fabricant in a prophetic story. It is pretty hilarious to think about a world without chilled noodles tossed with vegetables, leftover meat, and an acid-meets-oil dressing, but pasta salad is truly more American than Italian—with upscale grocers like Dean & DeLuca selling boxes of it to the newly named yuppies by the Volvo load.

Paul Prudhomme’s blackened redfish

Many assume that blackening fish is a long-followed Louisiana tradition, passed on from family to family in the bayou backwaters. But the style of cooking heavily seasoned flaky fish over extremely high temperature was the brainchild of the late chef Paul Prudhomme. People went crazy for it, and in 1985, Prudhomme—who was by then a cookbook and television star rivaling the celebrity of Julia Child—traveled to New York City to open a pop-up of his popular K-Paul’s Louisiana Kitchen. It was a sensation, and when city health officials tried to put a stop to the unauthorized restaurant, mayor Ed Koch stepped in to resolve the matter and put an end to the “gumbo war” that would lead to a permanent Nolita restaurant and a certified blackened craze.

Pesto unchains from Little Italy

Pesto, a specialty of Liguria, exploded on the New York City scene as Americans started to think about regional Italian cooking (also see: polenta, bruschetta) while simultaneously chefs placed their own creative stamp on the cooking by incorporating seasonal ingredients into the traditional preparations (see: substituting cilantro for basil). “By definition, the cooking was very ingredient driven,” says Waxman of an era when friends like Larry Forgione and André Soltner were telling him where to find the best rabbits or huckleberries in the New York City region. Pesto was like a great stage for a performance. “For many Americans basil and other condiments entered the lexicon only recently, but with a vengeance signaling a major shift in culinary tastes from the provincial to the cosmopolitan,” wrote Craig Claiborne in 1986 in a story documenting the new movement of food fascination. And indeed, by the end of the decade, pesto had supplanted itself as “the quiche of the ’80s.”

Microwave madness

While the rise of fresh, seasonal cooking was an undisputed facet of the era, the 1980s also ushered in an era of workaholism where time truly did equal money. And with the proliferation of frozen foods, coupled with a fast-food arms race, getting dinner to your table fast was more important than ever. Enter the now long-forgotten, often made fun of, microwave-cookbook genre. The Mastering the Art of French Cooking of the category is Microwave Cooking for One. It was written by a newspaper columnist named Marie T. Smith (1933-1987), a homemaker turned Melissa Clark of nuke cookery who was an expert in the field, attending microwave symposiums while writing regularly for the Plant City Post. I purchased the book, now in its fourth printing, because who doesn’t want a five-minute chicken Marengo? Also, microwave chocolate chip cookies? That’s as ’80s as Zubaz and the Dennis Eckersley mullet.