Bouncy, savory, and sometimes sweet, fish balls can shape shift from a creative filling to a crispy fried snack.

My love for fish balls hardened at a Passover seder. I was in elementary school, and my best friend’s family had invited me to their holiday meal. When it came time to serve the infamous gefilte fish, my friend and her brother put on their annual gagging faces in protest.

That year, in anticipation of this, my friend’s mother had spent hours chopping the carp and making a light soup for a homemade version of the holiday specialty, in order to avoid serving the jarred stuff that she knew her kids reviled. The results were mixed: They still hated the homemade version just as much, it turned out. I, on the other hand, loved it. I was embarrassed to love it at first, as my friend and her brother were so vocal in their disdain for the matzo-meal-bound morsels. In the end, encouraged by my friend’s mom, whom I felt bad for, I eagerly ate seconds. The spongy balls in a clear broth, eggy and rich with barely a hint of oceanic funk, were like enlarged and softer versions of the fish balls I ate regularly at home.

Squishy, mild-tasting, and soft—this is the fish ball epitome for those who worship at its altar. Current fashions might place crisp and golden-brown exteriors on a pedestal, but smooth and supple—preferably with a bit of bounce, so as to spring back when poked—is another textural ideal all its own. (In Taiwan, this texture is called “Q” or “QQ,” which best translates as “bouncy.”) As a quick meal or snack, my mother would pop a couple fish balls out of their freezer package and boil them with chicken broth. Once thawed, the ping-pong-size balls were like soft rubber, leaving teeth marks when bitten into, so smooth was their interior. Equal parts salty and sweet, their flavor seemed beside the point of their texture.

Like meatballs and meatloaf, fish balls and fish cake are traditional ways of using up animal protein scraps while stretching them farther with the addition of starch. These foods break into roughly two categories: the rustic, chopped type, such as loosely formed crab cakes one might order on the Maryland shore, and the uniformly textured, often industrially processed (at least nowadays) type that are sometimes described as “hot dogs of the sea.” There is plenty of gray area in between—think homemade terrines and mousses. In America, where the ideal meatloaf might be as chunky as a pint of Ben & Jerry’s, smoothly pureed fish balls and fish cakes don’t get much love. But elsewhere, this texture is more of an archetype. Foods formed from puréed fish paste–often fishmongers’ scraps–can be found in many parts of the world, where they are widely accepted as a snack, lunch, or dinner staple. They’re ordinary. From Bundt cakes of fiskepudding in Norway to Hello Kitty–shaped kamaboko in Japan, pulverized seafood bound with starch has long been a practical way of preserving fish and using up all its parts.

It’s often a familiar kids’ food that nobody grows out of. “Little kids will eat them cold as a snack,” says Nevada Berg, a Norwegian food writer and author of North Wild Kitchen, of fiskekaker and fiskeboller, or fish cakes and fish balls, in Norway. They derive from the same fish paste mixture, which is commonly purchased in the supermarket. The recipe for it in Berg’s cookbook calls for white fish such as cod, blended with milk, onion, potato starch, salt, and pepper in a food processor.

“The common texture is smooth and spongy,” she says. “When you press down on them, they should bounce back up.”

Söstrene Hagelin (“Hagelin Sisters”) is a famous fast-casual restaurant in Bergen, Norway, based on its founding sisters’ superlative recipe for fish cakes. The same batter is shaped into loaves, rounds, or heart-shaped cakes; it can be rolled into wraps or tucked into burger buns. Often, it’s griddled on both sides and served with brown gravy and a side of cubed potatoes and carrots topped with fresh chopped leeks. Any way you slice it, the fish paste it’s based on is a smooth and fluffy mixture of haddock and minimal spices, a sort of bologna of the sea. While fresh fish cakes are a coastal tradition, refrigerated, frozen, or canned fish cakes and balls are accessible throughout the region.

“All fishmongers sell them, often three to four kinds . . . with different herbs, and some with salmon, or white fish mixed with smoked salmon,” says Trine Hahnemann, author of Scandinavian Comfort Food, of premade fish cakes, or fiskefrikadeller, in Denmark.

In much of Asia, fish cakes are just as ubiquitous. They may vary from chunky and heavily spiced, like Sri Lankan fish “cutlets,” to airy and almost neutral tasting, as in Japan’s kamaboko. Narutomaki, the pink-and-white pinwheel slices of fish cake often found floating atop a bowl of ramen, is a classic of the more industrial variety. These fish cakes start with surimi, a forcemeat of fish and starch not dissimilar to that of the Hagelin sisters. The fact that one of its many manifestations is imitation crab, or crab stick, should not lead one to conclude that it’s a subpar stand-in for other seafood, but rather that it has a remarkable chameleonlike quality. For example, oden, a soup often slurped up as a late-night convenience-store food throughout Japan, highlights that diversity by featuring variously shaped and sized fish balls.

Fish balls may not be your idea of fodder for cultlike fetishization (nor an obvious subject for gushing appreciation pieces in food magazines). But there is a glimmer of renewed interest in fish cakes, balls, and loaves in the United States, where they have never been particularly loved outside of immigrant cultures that cherish them.

Calvin Eng, chef and co-owner of Bonnie’s, a restaurant in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, that honors the Cantonese food of his family, is an unabashed fish ball aficionado: “Fish balls and fish cakes are some of the most comforting, nostalgic things for me,” he says. Growing up in New York City’s Chinatown, Eng would often get them on a stick drenched in curry from a cart near the Grand Street subway station at the corner of Chrystie Street in Manhattan.

Eng has fashioned a fish paste according to his discerning principles, using a proportion of about 80 percent fish to 20 percent shrimp—the latter a must, he says, to give the final product more bounce. He prefers to use rainbow trout, although the classic Cantonese fish for fish paste is dace (read Leela Punyaratabandhu writing in TASTE on the cult of dace). It’s whipped up with Chinese flat garlic chives, ginger, garlic, cornstarch, and water chestnuts, along with salt, white pepper, and MSG for seasoning. For a limited-run takeout menu, while Bonnie’s closed its dining room due to the Omicron wave, the mixture was formed into thick patties and deep-fried to serve on a bun with American cheese as a variation on a Filet-O-Fish sandwich.

The formula makes for an exquisite fish cake for connoisseurs. The garlic chives lend an oniony funk and water chestnuts a delicate crunch, like sprinkles in a sundae. The deep-frying step imbues tiny, uniform air bubbles into its fluffy interior. Taking the concept to fish ball territory, it can be rolled into balls and fried or boiled for a superlative snack—see our adapted recipe.

For Bonnie’s dine-in menu, the same fish paste makes its way into a whole fish that has been completely hollowed out; the entire thing is then shallow-fried in a wok until the skin is crispy and the filling cooked through, then sliced cleanly along its length to reveal the fish cake–filled midsections. It’s served as a large-format entree for $52, and with lettuce and condiments to roll it up with, it easily feeds six in a multicourse meal.

Eng isn’t sure where his family got the idea from, but he says that once or twice a year, his mother and aunt would carefully debone a whole fish while keeping its skin intact, then puree the flesh with seasonings and starch and stuff it back inside the skin. Eng has scoured Chinese-language YouTube and found a couple videos that assured him the dish exists in China, too, though its origins remain somewhat a mystery. “I’ve been searching for this dish in restaurants and online for years, and I could barely find anything on it. Friends have told me a woman in Manhattan’s Chinatown used to sell this on the street out of her shopping cart,” he says.

A whole fish that has been surgically removed of its contents and restuffed is indeed not singular to Eng’s family, nor to China. This is the original method of making gefilte fish (which translates to “stuffed fish”). And poisson farci, a specialty of Saint-Louis, a coastal city in Senegal, follows the same method to a T. It’s included in Yolele! Recipes From the Heart of Senegal by Pierre Thiam.

“To my knowledge, the Saint-Louisian stuffed fish is a traditional recipe. However, food has the particularity to transcend borders,” says Thiam.

But what could be the reasoning for deconstructing and restuffing a whole fish? According to Leah Koenig, author of, most recently, The Jewish Cookbook, gefilte fish came about because of prohibitions in Jewish law against certain activities on Shabbat, or the sabbath. One of them pertains to sorting: “When you’re eating fish, you’re not supposed to separate the bones from the fish, because you’re not supposed to separate the undesirable from the desirable,” says Koenig. To get around that, families would buy fish and debone it before the sabbath, stuffing it with an entirely edible, boneless filling.

This laborious procedure is no longer the de facto one for gefilte fish in America, where the dish has evolved and become industrialized. Instead, gefilte fish is now more recognizable as precooked, football-shaped fish balls preserved with a clear gel in a jar. While convenient, these jarred versions—with all that wiggle—have seared gefilte fish’s reputation as a less-than-great dish during the Jewish holiday of Passover.

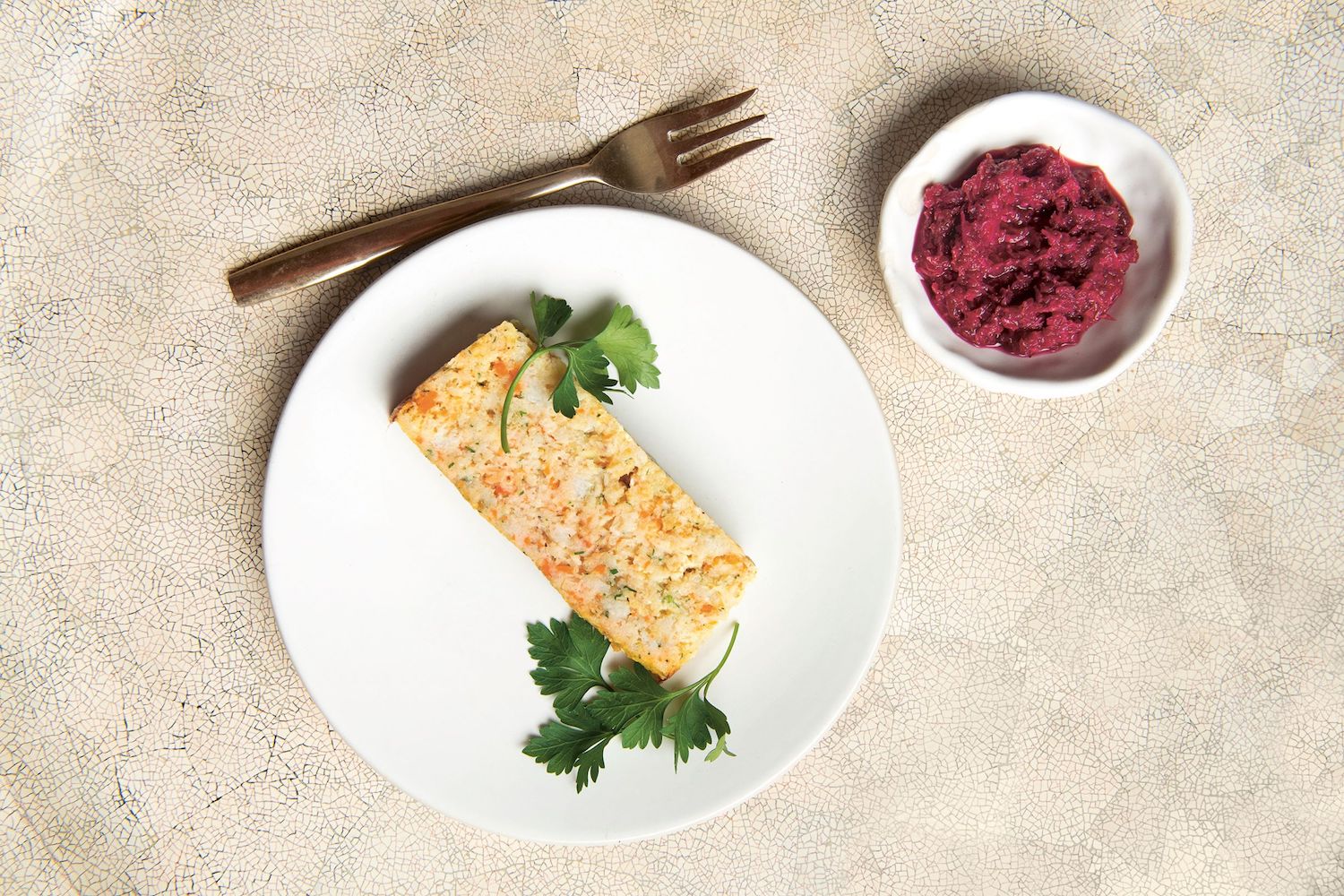

“There is a lot of media in TV and movies where gefilte fish is made fun of by Jewish writers, and it’s almost a part of cultural Judaism that laughs at its own culture, which is its own internalized anti-Semitism or xenophobia,” says Jeffrey Yoskowitz, cofounder, along with Liz Alpern, of the Gefilteria, which sells artisanal gefilte fish through online retailers and in fish stores in New York City. Made with responsibly sourced steelhead trout, salmon, and whitefish, its namesake product features two layers of pastel peach and off-white fish paste formed in a neat, rectangular terrine. It’s sold frozen, ready to thaw and slice.

“I like to whip it up before baking so that it’s very smooth—not quite a mousse but very fine,” says Yoskowitz of his ideal texture.

It has, he says, upended the image of gefilte fish for many in his generation who grew up wary of anything with clear gel in it. But gefilte fish has many more dimensions. As Koenig points out, there is a world of gefilte fish from Jews with more colorful food traditions, such as gefilte fish à la Veracruzana in Mexico. And it has inspired other food traditions as well—England’s fish and chips tradition may have originated with fried gefilte fish balls introduced by Sephardic Jews in the 18th century.

Fish balls may never be as popular as meatballs in the United States. But the care and attention being paid to these traditional foods by some chefs and writers today underscores just how well-loved they really are, when prepared according to certain ideals. As reimagined versions of fish cakes and balls are introduced to new audiences, their associations and reputation may change. But one thing is for sure: a good fish ball will always bounce back.

Shelve It explores the world of groceries, from the fluorescent-lit aisles to the nooks and crannies of your cupboard. We dive into why certain ingredients got pantry staple status, the connection between cookbooks and buying habits, the online-ification of grocery shopping, and what gets shelved along the way.