Crack open any cookbook and you are confronted with a dizzying collection of recipes. If you are actually going to make something for dinner (and it’s OK if you’re not!), choices need to be made. In BREAKING IN, we prepare a few interesting recipes to get a feel for the book. This is not a review, but rather a firsthand experience of cracking the spine of a new cookbook.

Twenty-five years ago, when I was a teenager living in Williamsburg, Virginia, I ate my first bowl of pho—at a small, chic, family-run restaurant called Chez Trinh. That Vietnamese beef noodle soup—it is no exaggeration to say—changed my life.

Pho seemed to me the perfect food. The broth was at once deeply meaty yet light and clear, perfumed with star anise and cinnamon and sweetened with charred onions. I loved how pho could be customized to my individual taste: I could pile the bowl with bean sprouts and Thai basil, douse it with spicy saté or Sriracha, or keep it plain. Perhaps most of all, I craved the noodles, slippery and slurpable.

I became smitten with Vietnamese food. A few years later, finishing college, I started making plans to move to Ho Chi Minh City, where I dreamed I would eat pho and all kinds of other theretofore-inaccessible delights every single day. And that’s pretty much what I did for the year after college. I ate bánh mì and fried spring rolls stuffed with crab; I assembled rice paper rolls with grilled pork and star fruit and herbs whose names I still don’t know; I ate buttery croissants and oily coffee, and grilled mussels doused with coconut cream and sprinkled with crushed peanuts. And yes, I ate a whole lot of pho, for breakfast, for lunch, and sometimes late, late, late at night.

My love affair with Vietnamese food did not end when I returned to the United States. I continued to eat pho whenever possible, particularly when I left home in New York (where it’s pitiable) to visit California (where it’s incredible). But over the past couple of decades, as I’ve raised a family and learned to feed them, I’ve almost never cooked Vietnamese food myself. In fact, since that first revelatory bowl at Chez Trinh, I’d made pho at home a total of three times in 25 years.

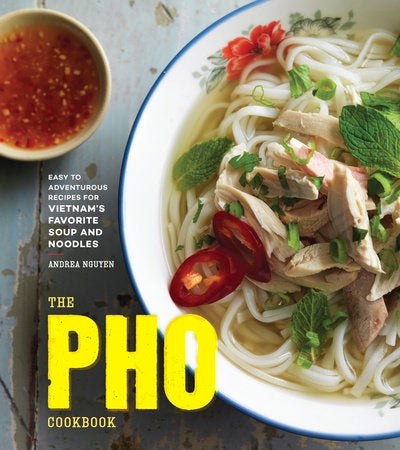

That is, until The Pho Cookbook landed in my kitchen. The sixth cookbook from California-based Andrea Nguyen—whose well-regarded previous cookbooks have covered tofu, dumplings, bánh mì, and Vietnamese cooking in general (and who is, full disclosure, a friend of mine)—sets out to be a complete manual for making Vietnam’s national dish. Which, given pho’s popularity, is a novelty: Though it gets pages of attention in other cookbooks, few writers in English have devoted an entire volume to the noodle soup. Even Nguyen herself was surprised when her publisher suggested a pho cookbook—until, she writes, she realized “the world of pho was unusually rich with culinary and cultural gems.”

Her approach is admirably clear: Identify pho-making styles that range from traditional (Hanoi vs. Saigon) to “quick” to “adventurous” (Wok-Kissed Beef Pho, Lamb Pho, and so on), and in about 150 pages show readers the ingredients, techniques, and specific recipes they need to make them (along with some snacks and drinks). Nguyen makes no grand claims for what pho should be—she’s a researcher and an analyst (an opinionated analyst). Her essay on the history of pho, for example, traces its origins not to pot au feu (as many assume), but to the early 20th-century intermingling of French, Chinese, and Vietnamese peoples and dishes in the city of Nam Dinh, south of Hanoi. Read it, memorize it, amaze your pals over noodles!

As I scanned the book, I began to feel nervous. Was I seriously going to attempt this? For so long I’d avoided making pho, telling myself I didn’t really know the right balance of meats to use for the stock, or that I only knew one store in Manhattan’s Chinatown that carried all the herbs I’d need as accoutrements, or that I could only find two brands of vacuum-wrapped fresh pho noodles, and who knew if either was any good?

I mean, I understood what was behind my reluctance. I loved pho, and I didn’t want to spend half a day and a decent amount of money completely fucking up something about which I had such powerful feelings. To fail at something you like is a disappointment; to fail when love is on the line is soul-crushing.

But what is love without risk? Which is why, in mid-February, I set about collecting ingredients in Chinatown. The first recipe I was attempting was not the classic noodles-in-soup pho but pho xao ga, or Saté Chicken, Celery, and Pho Noodles, a straightforward stir-fry of the titular ingredients. Well, fairly straightforward: Nguyen’s recipe called for homemade saté, an intense blend of dried shrimp, lemongrass, garlic, shallots, and fish sauce that is, in Nguyen’s words, “addictively good.” (Bottled versions are readily available, often with slightly different ingredients.) And it also asked for something that should have been basic, but in my mind suddenly wasn’t. Dark soy sauce. A mere half teaspoon was all I’d need for this recipe, but it felt like a gallon of anxiety.

Because WTF did Nguyen mean by “dark soy sauce”? That is, if you examine the soy sauce shelves of any decently stocked Asian supermarket, you’ll find not only light soy sauce and dark soy sauce but also dark, sweet soy sauce (I had a faint memory of using this thicker version in a Thai or Malaysian stir-fried noodle dish), not to mention soy paste (thick and a little sweet, it goes in my Taiwanese lu rou fan), seasoned soy sauce for seafood (which I don’t understand), and wheat-free tamari. Some of these are labeled “superior” as well, and there are Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and other national and regional varieties. (Taiwan, for example, doesn’t distinguish between light and dark soy.) Also, in the bottle, they all look perfectly identical.

Rushing around Grand Street, I was almost paralyzed by my knowledge of the options, which included, per the cookbook, substituting “a big pinch of fine sea salt” plus dark molasses, neither of which I had at home anyway.

So I texted Andrea Nguyen—and in my fluster tapped “soybsauce” instead of “soy sauce,” leading her to think I meant a totally different, thicker type of hoisin-like soy-based sauce. (Oh, God, kill me now.) Finally, after much back and forth, she figured out what I meant and sent me a photo of Pearl River Bridge brand superior dark soy sauce, whose Chinese label translates as “aged soy sauce king,” the idea being that aging darkens and sweetens. And since I couldn’t find that, I just bought the first bottle I saw that was labeled “dark soy sauce.” Victory!

Then I went home, blended up the saté, marinated the chicken thighs, and sloppily stir-fried everything together, neglecting to clean out the wok between stages (as directed) because my kitchen sink is small and my daughters were hungry. The thick, ribbony rice noodles got a little stuck to the pan, and therefore chopped up and uglified, but my family seemed to like it, even if the kids picked out all the celery and I needed to mix in extra saté to give it a stronger punch of garlic and lemongrass. It was so easy to make (chop, marinate, stir-fry, serve) that I don’t know why I haven’t yet put it in regular rotation—minus the finicky noodles, to serve over rice.

Easy stuff out of the way, it was time to stop stalling. It was pho time.

Except, actually, pho is easy, too. From my three previous attempts (and many years of eating it), I knew the basic process: Parboil a bunch of beef bones. Char onions and ginger over an open flame. Simmer them all along with Chinese rock sugar and a panoply of spices—star anise, cinnamon (or cassia bark), fennel, cloves, coriander, and Chinese black cardamom (a.k.a. red cardamom, or cao guo). Honestly, that’s about it. There’s your pho broth. All you have to do is cook some noodles, plop everything in a bowl, and serve with the proper garnish.

Except there are ways to obsess. What I’d always wanted on my few pho-making occasions was an expert guide. Which cuts of beef to use, and in what ratio, and why, and with how much water? Which of the spices to deploy, and in what proportions? These are the fundamental questions of pho-making, and if I’d been making the dish weekly for 25 years, I might’ve figured out the answers already.

And that’s where The Pho Cookbook shines. In a section called “Blending Bones,” Nguyen writes, in her refreshingly direct style, of what to use and why. Marrowbones, she suggests, are “superb” but often costly, and so one should use a 1:1:1 ratio of marrow, knuckle, and neck—“which, respectively, lend fat, body, and meatiness.” What about oxtail, so often recommended? Nguyen calls it “a pricey option that often dampens flavor and yields dull broth lacking dimension.” Select bones with some meat still on them. Have a butcher cut the bones into three-inch sections. Leave exotic cuts like “crunchy flank” to restaurants. For Hanoi-style pho, include a pig’s foot. “Adding pizzle to the bowl,” she notes, “does not increase potency.”

Good to know—all of it! From there, it was a mere four hours or so till dinner. I charred my onions and ginger over a gas flame, sending ash all over the stove in just the way my wife loves. I parboiled six pounds of marrow, knuckle, and neck, then rinsed off impurities and returned them to the pot along with the aromatics, dried spices, and a slab of brisket. And while it all simmered (“gently,” per the book), I prepared the ultimate garnish platter: bean sprouts, lime wedges, scallions sliced on a sharp bias, chopped bird’s-eye chiles, Thai basil, mint, soapy sawtooth leaf, citrusy rice paddy herb, and my own homemade Sriracha-style hot sauce.

The sun went down. My stomach groaned. The children whined. Had the broth gently simmered enough? It didn’t matter now. I strained the broth into a fresh pot and plucked meat from the bones. I set water to boil for noodles and thinly sliced a semifrozen chunk of cartoonishly marbled tri-tip (one of Nguyen’s recommended cuts). I arranged the bowls for assembly-line production. I cooked noodles and ladled, cooked and ladled.

Everything looked right. Everything smelled right. Everything tasted…

Does it matter? After all the shopping, the cooking, the assembling, the effort, does it really matter? “How did it taste?” is the wrong question here. What matters to me—and what I think should matter to you—is: Did this change anything? Did having all of Andrea Nguyen’s impeccably researched and tested cooking advice transform pho from a restaurant treat into an everyday meal? Will this book make a difference?

The answers to those questions depend less on the book than on the reader. If you crave pho, don’t have access to Vietnamese restaurants, and can get ahold of the necessary meats, spices, and herbs, this book will vastly improve your noodle-soup-eating existence.

For me, however, I don’t know that it turned me into a committed pho cook. The batch I made—and the batch of chicken pho I prepared a week later—was pretty decent. The mouthfeel was incredible, but the broth wasn’t as beefy as I’d hoped. More neck bones next time, I guess, or maybe I need to simmer longer, or maybe when Nguyen writes “simmer gently,” her sense of “gently” is rougher than mine. But next time may be a long time coming. The special ingredients (particularly the herbs, which I consider essential) are a pain to acquire, and my freezer is too small to hold quarts of broth in reserve. My home will not become a pho home. As much as I love pho, I cannot marry it.

But you know, I’m okay with that—thanks again to Nguyen, who begins the book by pointing out that the romantic language of pho is a part of Vietnamese culture. “Rice,” she writes, “is the dutiful wife you can rely on, we say. Pho is the flirty mistress that you slip away to visit.”

And so slip away I shall, as often as my wife will let me, for bowls of pho, from New York to San Jose to Nam Dinh, slurping lustily and without a care, leaving the prep and cleanup to someone else, and paying proudly for the privilege. Pho may now find its place in my home kitchen a little more often—let’s call it an annual project—but for the most part, I’ll be down with OPP: other people’s pho.