David Hsu, an author and social scientist, believes that food is the way to fight back against America’s growing social isolation.

I began following David Hsu (pronounced “shoo”) on Instagram about a year ago, mesmerized by the incredible and impeccably styled meals he cooked in his downtown Los Angeles apartment: fried chicken sandos cooked crisp and browned to restaurant perfection; lush green salads jeweled with slivers of California citrus and avocados; fizzy, blush-pink cocktails that would look perfect set next to any rooftop pool in the city.

A few months after we began following each other, Hsu invited me to have coffee with him so we could meet “outside of the screen.” A few weeks after that, he hosted a small happy hour at his apartment; his guests included an anthropologist, some food-justice friends, and even a few of my own creative friends whom I had no idea knew Hsu.

In an age where food feels more like social currency and less like a reason to find common ground, Hsu’s genuine hospitality is sincere and open-hearted. A Princeton- and Duke-educated social scientist who currently works as the director of business innovation at Propper Daley, a social-impact agency, he is deeply curious about what it means to live in a society where social isolation touches all groups of people.

This curiosity lead to Hsu to write Untethered, a book that explores how people become isolated from one another. His initial goal was to create a primer for community leaders, philanthropists, and entrepreneurs who have the resources to help steer people away from social isolation and toward connection and community. David sees and participates in this kind of work as a board member at LA Kitchen, a nonprofit organization that teaches culinary skills to the formerly incarcerated, who in turn use them to provide meals to aging and impoverished Angelenos.

What makes Untethered remarkable is the way it uses a mix of sociological language, statistics, and analyses of different kinds of social isolation to illustrate that while we are more connected than ever before, our connections are tenuous at best because they are largely digital and not in-person, real-life connections. According to the book, 40 percent of American adults have reported feeling lonely on a regular basis.

I feel anything but lonely when I visit Hsu on Easter as one of three guests at a gathering that also includes Hsu’s partner, Pete, and a close friend of theirs (also named David, who lives far enough west that they don’t see each other often—a very Los Angeles phenomenon that usually contributes to a deepening sense of isolation). We chat about the challenges of having friends who live on opposite sides of the city, the moments in which we’ve all felt the scourge of isolation due to those invisible but felt borders, and how these meetings over food make us all feel supported, seen, less alone.

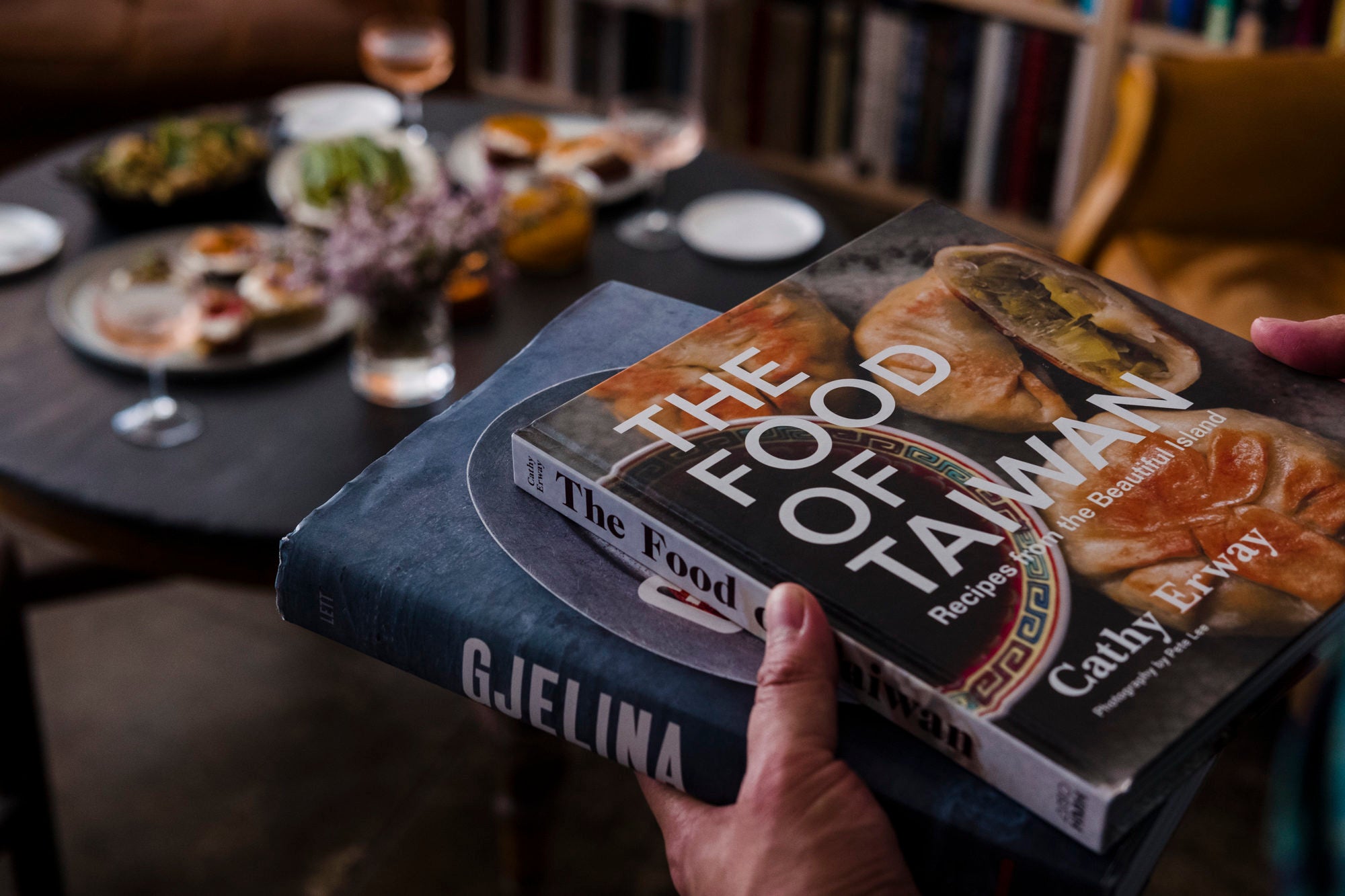

After Hsu deftly seasons and breads chicken, he uses chopsticks to transfer it to a smoking-hot cast-iron pan, giving it a quick sizzle as he adds fresh basil for additional flavor. This particular dish is adapted from one of his favorite cookbooks, Cathy Erway’s The Food of Taiwan, which has helped him to learn to cook with the flavors from his childhood in the San Gabriel Valley as the first-generation son of Chinese immigrants via Taiwan.

But Hsu wasn’t always adept in the kitchen. “I learned to cook after college when I was just eating, like, grocery store rotisserie chicken and frozen dumplings constantly, so I just started reading [cookbooks]. I love backwards-engineering things I have had at restaurants or bars,” he says, leaving the chicken to drain and moving onto a lovely blush cocktail inspired by a drink he once had at Gjelina, a hip restaurant-bakery just a short walk from the Venice Beach boardwalk.

Sitting around a circular wooden table, surrounded by books stacked on the floor and crammed into bookshelves, we set about the business of catching up and begin to lament “hospitality,” or the lack of understanding of what it means to be hospitable. “[Hospitality] is not about going out to restaurants. It’s not about fancy food, per se,” Hsu says. “It’s about using food to bring people together, so that’s part of my work.”

He sees hospitality as the solution to a lot of our social ills, particularly in the potential of food to support not only our sustenance but also that of our neighbors, especially those who have been marked as outcasts or unworthy of our time and concern. “I read this study where if two people eat the same thing, they instantly feel better about each other,” Hsu says. “Turns out ordering the same thing as the other person on a business meeting is a great strategy for building a bridge. The way of cooking that I have come to love is very much connected with movement-building. We often underestimate the power of food in community-building for people of color, the LGBT community, people in the margins.”

When it comes to creating his own gatherings, Hsu thinks about how to build deeper ties rooted in face-to-face interaction, shared over meals: This, he says, is hospitality. As such, he’s kept every menu he’s ever created over the last 15 years. “Part of it is I have archival impulse, so I like marking moments from a simple cocktail party to a chocolate-themed birthday party to Shared Plates,” he explains. “The most memorable points of my life are from around a table.”

Many of us would agree that the moments worth remembering in our lives have been largely punctuated by food shared with a group of loved ones, seated at a table where we feel less like strangers and more like kin. What I appreciate most about Hsu’s cooking and his use of Instagram to document those meals is the reminder that images of food without context don’t tell the whole story, and because they don’t, it’s important to reach out to strangers to share both meals and stories.

“Making strangers feel less strange: that’s what hospitality really means to me,” Hsu says. “Food just happens to be a really powerful and easy way to do that every day.”

Do the foods we pack into our pantries and refrigerators give us insight into what it means to be American? We think so. In this series we visit home kitchens in Los Angeles to explore the nuances of home cooking in 2018.