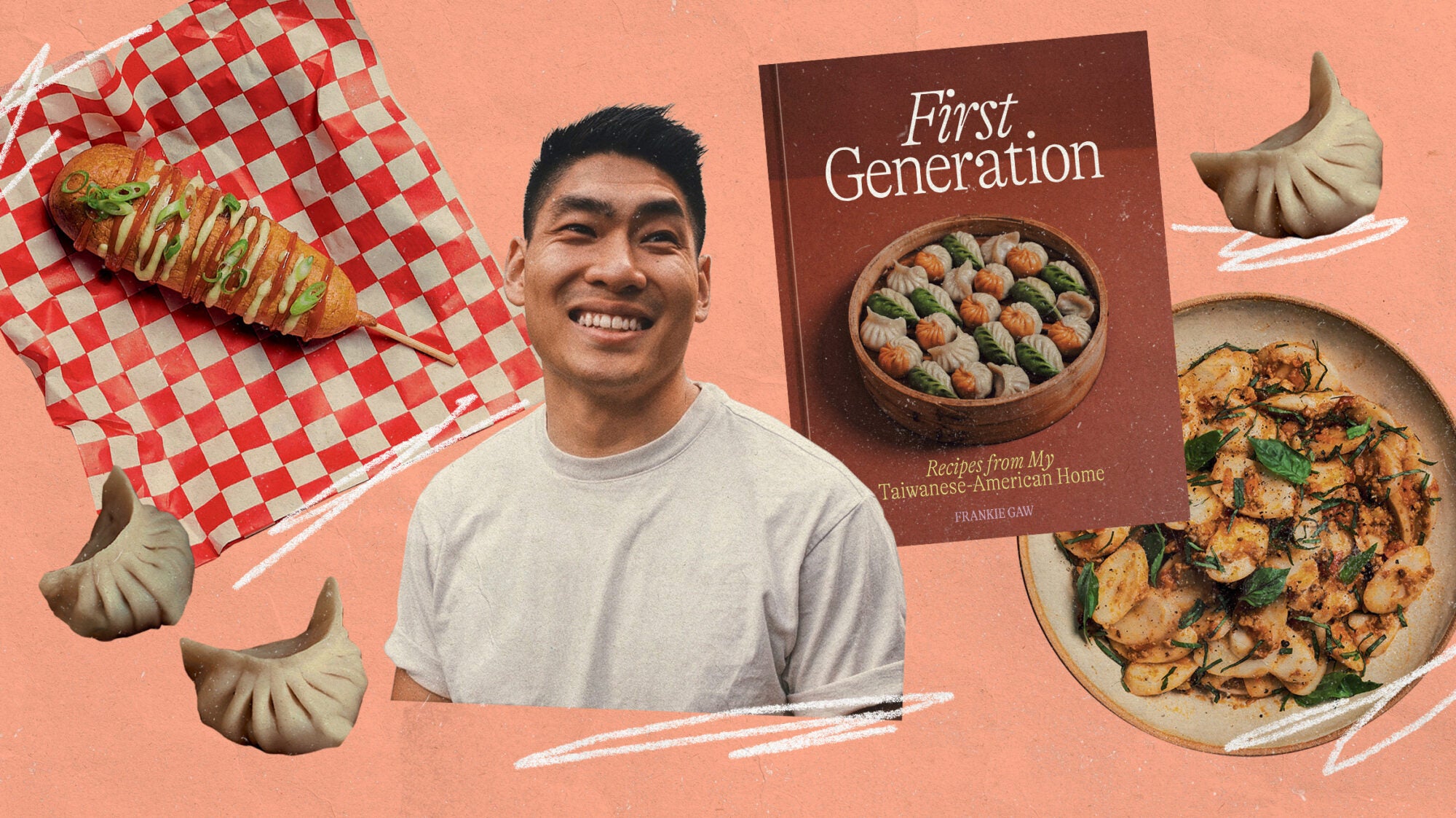

His debut cookbook, First Generation, celebrates Taiwanese-American cooking with a heavy dose of Y2K nostalgia.

“I am Taiwanese American.” The first line in Frankie Gaw’s debut cookbook, First Generation: Recipes from My Taiwanese-American Home, is simple and declarative, a statement of fact that feels like it might roll effortlessly off Gaw’s tongue if you met him in person. But Gaw, whose parents emigrated from Taiwan to the United States in 1985, admits that figuring out how to feel confident stating his identity as Taiwanese American—not as two distinct, separate identities—was a learning process.

Gaw grew up in suburban Ohio, eating his grandmother’s steamed baos and chicken nuggets from McDonald’s. It wasn’t until he was working as a product designer in his early twenties that he began asking his grandmother to teach him the recipes he grew up loving, like liang mian (a cold ramen salad with ginger and garlic peanut sauce), braised peanuts, and pork dumplings. As he writes in the book, learning his grandmother’s recipes proved to be a way for Gaw to process his emotions as he struggled to come out as gay after his father’s recent death. It also became a creative outlet as he began to give family recipes his own spin, heavy on the Doritos and sugary breakfast cereal.

Gaw began documenting his recipes with radiant photos on his website, Little Fat Boy, which won Blog of the Year from Saveur magazine in 2019. His cookbook, shot by Gaw in his attic and designed to evoke vintage Chinese cookbooks, is an extension of the blog, initially started to document his grandmother’s recipes. Gaw’s book not only inspires you to want to re-create his observant, absurdly fun, and nostalgic recipes—think Cincinnati chili with hand-pulled noodles, red pepper scallion pancakes designed to mimic game day nachos with a cashew crema and accompanying red pepper dip, or brownies made with Reese’s Puffs cereal—but to be unafraid to tell your story. Through his highly personal stories and occasional essays, often presented as interludes between chapters, Gaw encourages readers to capture their history and live fully in whatever identity they wish to encompass. And if you’re not sure where it will lead, don’t worry: Gaw is still figuring things out as well.

You use a lot of foods from the late ’90s and early 2000s as inspiration or as ingredients in your recipes, especially in the dessert section, where many of the recipes use popular cereals—Reese’s Puffs, Cinnamon Toast Crunch, Cap’n Crunch. How did you think about incorporating these particular touchpoints into your recipes?

I knew I wanted to do a cookbook that represented my background specifically, and I had never seen an Asian cookbook represent the experience of a first-generation person. So I thought, “How do I capture that and represent that in a way that feels authentic?”

I grew up with these very distinct cultures, and it’s always been this balance between the two: I’m Taiwanese by heritage, but I grew up in the Midwest, and I’ve struggled with both. I think there’s something super interesting about celebrating that messiness and figuring that identity out. My American side, my Ohio side, is all those foods: Gushers and Fruit Roll-Ups and all these things that kids used to eat.

There’s something very nostalgic about those foods, and they capture a specific period in time. I wanted the book to be nostalgic and sentimental; those foods were part of that, and I intentionally tried to capture this moment in time.

Many recipes in First Generation are riffs on things you learned from your grandmother. When did learning these family recipes become vital to you?

Around 2015 or 2016. It was this weird time when I was sort of having an existential crisis. My dad had recently passed away, and it was just that early-twenties period when I was trying to figure myself out as an adult. I was also trying to figure out how to come out; I hadn’t come out at that point yet. I just had all these questions about identity—who I was and what my purpose was. So I wanted to start with something I know brings me joy and comfort: the food I grew up with.

I started going to my grandma’s house every few months to learn the dishes that brought me comfort, because I was going through so much. I would record her making the steamed buns and dumplings I loved so much so I could make them later at home. I started documenting it on social media, partly because I was finding so much joy in making something that brought me a lot of comfort and being able to re-create that nostalgia and that memory of my childhood for myself as an adult.

Gradually, I started putting my spin on things as I became more familiar with ingredients. I’ve always loved doing things creatively and doing things with my hands. So I started trying things out, figuring out what I like to cook, and using my grandma’s recipes as a base.

You said you love doing things with your hands, which feels very apparent in the book. There’s a physicality to the way you write recipes, and you visually represent how to make many of your base recipes using drawings and step-by-step photos. Did you intend for the recipes to feel so visceral?

I’ve always been very visual, and I’ve always learned best with visual metaphors and being able to describe the physicality of something. But I think it’s just how I’ve watched my family cook.

I think this is similar to other families, but whenever my grandma talked about cooking, it was always about physical movements. She never measured anything, and things were done by feel. For example, when I write about kneading dough for dumplings, she’d say that the dough has to feel like a butt [laughs]. I don’t know how else to describe it.

So now, I don’t even need to say how long to knead—as long as it’s like a butt! That always stuck with me and translated to how I described the food in the cookbook.

In highlighting the physicality of your recipe writing, we also need to discuss how you drew all the illustrations and photographed the entire book.

Yeah, I did. I shot it all in my attic. I’ve always loved photography, and I studied industrial design, so I knew I wanted to be the book’s creative director. I think there was just something about being able to represent that food and shoot the food that I grew up with, to have that control over the creative direction and the styling that was important to me.

But if I ever did this again, I would definitely hire somebody—because it was so much work!

You describe the process of writing the cookbook as a form of time travel. Is there a memory you stumbled upon that you looked at differently or that carries new weight as an adult?

I feel like the cookbook itself was a way to process my feelings about my identity. Writing the recipe blurb for the scallion pancakes, for example, sparked a memory of camping when I was a kid. My dad made these scallion pancakes to take with me, and I tossed them out as soon as I got to the camp. I didn’t want to bring attention to my Asianness in front of all my white friends.

That’s a memory I didn’t necessarily forget, but I never really reflected on the impact of my actions. At the time, I was just a kid in Ohio and one of the only Asians. Writing these recipes made me dissect how I dealt with my identity, and I discovered that I treated my dual identities as separate, which I hadn’t thought much about. It was like my home life was my Taiwanese identity, and anytime I stepped out of the house, it was a switch. That’s something I never thought through until I was thinking about the actual recipes that sparked those memories.

“When I write about kneading dough for dumplings, she’d say that the dough has to feel like a butt. I don’t know how else to describe it.”

When did it start feeling okay to mix the two identities?

It took me a minute. I don’t think I was fully comfortable with it until I came out in my early twenties, and I feel like coming out was a massive step for me in the sense that it was the most vulnerable I had ever been, and I think that experience unlocked a lot of other things for me.

It allowed me to look at other parts of my life and be like, “Okay, what are the things that I’ve suppressed that, in the end, don’t matter? It’s about what I care about and who I am as a person that matters first. I have to focus on myself before I think about what others think of me.”

Whether it’s me being gay or me being Taiwanese or American, I think all these things are equally of value, and they’re all worthy of being celebrated.

You’ve built multiple points of connection in the book while remaining highly personal. What would you hope a reader takes from First Generation?

First and foremost, I hope people feel represented by this book and encouraged to tell their own stories. I wouldn’t have written this type of book had I not seen writers like Eric Kim. He had this column called Table for One at Food52 where he talked about being single and gay. Had I not seen that, I might never have mentioned my gay identity in a cookbook. Or even beyond food, reading books from Asian authors about immigrant families, like Pachinko. It’s fiction, but it is about a Korean family through multiple generations, inspiring and empowering me to write my own family history.

I also want people to connect with the humor and the nostalgia, because I feel like it does capture a moment in time, especially for millennials. I hope it brings some joy to people who lived through that same period. But I want people to know that I am also figuring things out with my food and myself. The book isn’t a canonical encyclopedia of Taiwanese food, and I’m not a Taiwanese food expert. I know what I know from personal experiences and what I’ve gone through with my family. I’m a work in progress, and the food is very much a representation of that perspective.

3 EXCITING RECIPES TO TRY FROM FIRST GENERATION: