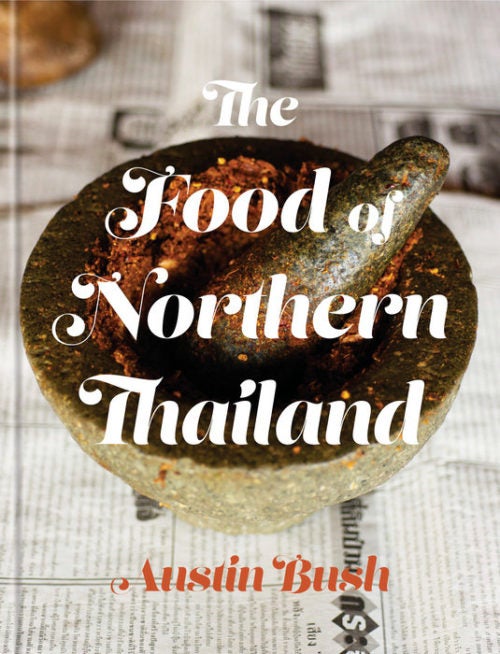

After 13 years and 66,000 miles driven a cookbook—The Food of Northern Thailand—has arrived.

The first thing I did was buy a truck. Why a truck? I suspected that I might have to go off-road, and I also wanted a place to toss my bicycle on long research trips. So I went to a dealership in Bangkok, exchanged cash for a new Toyota Hilux, loaded it up with light stands, tripods, a softbox, reflectors, cameras, notepads, a laptop, and my bike, and the next day I was off; I was going to write and photograph a book about the food of Northern Thailand.

This was not a rash decision. I’d had the desire to write a book about Thailand’s regional cuisines since I started working as a Bangkok-based writer and photographer around 2005. Indeed, I began work on it then, but in looking at those photos and text today, the stuff is cringe-worthy and amateur. I quietly put the project aside, and it took almost exactly a full decade of writing, photographing, traveling, making contacts, learning the language, and assimilating knowledge before I felt ready to approach it again.

So I drove. Northern Thailand, with a core roughly the same size as Indiana, borders Myanmar to the west and north, and Laos to the east. From Bangkok it takes about 12 hours to get to Chiang Mai, the region’s largest city and its cultural capital—if, like I did, you get lost. And it’s there that I began. I’ve been writing guidebooks for Lonely Planet since 2007, and Northern Thailand was my turf, so I already knew many of the dishes I wanted to feature. It was simply a matter of getting my foot in the door.

Two friends’ moms showing me how it’s done in Nan Province (left) and Chiang Rai Province (right)

You see, to make a cookbook, you need recipes. And I wanted these recipes to come directly from the people of Northern Thailand. To that end, I employed a variety of techniques. If I was approaching a restaurant, I would eat there a few times, show interest and ask a lot of questions. As a white guy from Oregon who speaks fluent Thai, I had an inherent advantage: I was clearly an outsider, but one who could communicate, and people were chuffed that someone like me showed an interest in their noodles, their grilled dishes, their curries. When I felt that I’d established a relationship, I’d reveal my intentions in a conversation that usually went like this:

“I’m a writer and photographer doing a book about food in Northern Thailand. I really love dish X. Would it be possible for me to see how it’s made, and to take some photos for my book?”

“Why? Are you opening a restaurant?”

“No. I’m a writer and photographer doing a book about food in Northern Thailand.”

“So you’re going to take my recipes and open a restaurant?”

“No. I’m writing a book.”

“Do I have to pay you?”

“No. Of course not. I’m just writing a book.”

“Sure. Whatever.”

The vast majority of restaurateurs and vendors were fine with me crashing their kitchens, blasting photos, and asking my stupid questions. And it’s from them that I sourced some of the more refined recipes in my book, such as the tofu-tender chicken laap that was, unusually, seasoned with fennel and dill seed, or a noodle soup that gets its deeply savory flavor from minced pork belly simmered with natto-like fermented soybeans.

Northern Thai–style chicken laap and natto-like fermented soybeans, both in Chiang Rai Province

Another source of recipes was homestays. In remote rural Thailand, in communities too small to have a hotel, locals come together to open their homes to guests. For a fee of $10 or so, you get a mattress on the floor and a meal or two. I would research these online and call ahead, making it very clear what I was doing and requesting to stay with the family that had the strongest reputation for cooking. Homestays proved to be one of my best resources, as home-based cooks and housewives had no qualms about sharing their recipes.

Some of the most unique recipes in my book, from a slightly astringent soup of free-range chicken and banana blossom to savory mushroom- and tomato-flavored balls of rice, came from homestays. But having such an intimate view of people’s lives can, occasionally, be a sobering reality check. While I was driving around the country in my fancy new truck on my frivolous pursuit, I encountered people dealing with serious poverty, health problems, lack of infrastructure, and corruption. I was occasionally hit up for money. And more than once, my homestay fee ended up in the local liquor shop, something I didn’t feel great about.

Fellow photographer Christopher Wise in our bed at a homestay in Mae Hong Son Province (left); a typically wild homestay evening in Nan Province (right)

When I finally got in a kitchen, I started by taking furious notes, scribbled both in English and Thai. My iPhone became an invaluable research tool: I used it to snap photos of ingredients and to videotape the more complicated cooking techniques (in particular, video is the only way I’d ever be able to recall the complicated and beautiful ways Northern Thais fold banana leaf to wrap ingredients and dishes). And of course, I took photos with my DSLR (a Nikon D800, typically mounted with a 16- to 35-mm wide-angle zoom, or a 90-mm macro lens).

I would take casual photos of people cooking—when I remembered to and/or when my hands were free—followed by more composed images of the finished dishes. One thing I’m particularly proud of is the fact that all the dish shots—“beauty shots,” as they’re known in the cookbook industry—in my book were shot on location, where the dishes were made, not in a studio in New York City. Folks would slap a dish down and stare at me impatiently while I fiddled with my portable studio (a SB-900 strobe mounted on a light stand and shot through a softbox; natural light is a rare commodity in Northern Thailand’s kitchens), stood on chairs and bumped my head into things to get the right angle. Other than tweaking a garnish here and there or shifting the orientation of a plate, I did no food styling at all—what you see in the book is exactly how the dishes were served in Northern Thailand.

Attempting write a cookbook at Andy Ricker’s house in Chiang Mai

Indeed, the approach that I stuck to throughout the making of this book was that of a journalist. I’m not a journalist, but I hoped that this approach might shield me from the inevitable critiques of being a white guy taking a deep dive into a culture that isn’t his own. In following the tenets of journalism, I hoped that this would emphasize my neutrality, my role as an observer rather than an expert, and would also keep me aware of certain ethical standards; I had no desire to profess ownership over this cuisine. I simply wanted to record it as accurately as possible. In the end, the recipes in my book came from homes, stalls, restaurants, academics, housewives, home cooks, government officials, writers, and agriculturalists. Being able to peek behind the curtain was always revealing, but it wasn’t always pretty.

Not-unusual kitchen scenarios in northern Thailand, both in Chiang Mai Province

Some stats. Miles driven: 66,000. Accidents: 0 (but lots of dents and scratches). Words I was meant to submit: between 55,000 and 65,000. Words I ultimately submitted: 98,204. Weird things consumed: raw blood, pig teat (it has a milky flavor that’s even more unpleasant than that sounds), a dip of pounded tadpoles, ant eggs, raw buffalo, beef bile, bitter greens that sucked the moisture out of my mouth. Times I got sick from eating weird shit: 0 (no lie). Places where the book was written: Mae Hong Son, New York City, Macau, Lisbon, and Bangkok.

In all, it took more than a year of research to obtain everything I needed; I spent more than half of 2016 on the road in Northern Thailand, driving the truck, tracking down leads, taking notes, and shooting photos. At one point during the year, my relationship fell apart, in part, I suspect, due to my emphasis on professional over personal life. What had previously felt like freedom began to shift to isolation and loneliness: day after day, week after week, month after month alone, at shitty hotels in small towns. The work, when I was in the thick of it, was fulfilling and engaging, and everything outside of it was a chore.

One of the dreariest hotel rooms I stayed in, near the border with Laos in Nan Province (left); getting a haircut on the road for about $1.50 in Lampang (right)

And then this summer, in New York City, almost exactly three years since I’d proposed it, after roughly two years of research and a year of writing, I was holding it in my hands: my book. I had imagined this moment many times during the course of my research and thought I would feel some sense of profound fulfillment, a new Austin Bush in a new place in the universe: I wrote and photographed an entire fucking book. But I was the same person. In my more cynical moments, I felt bitter that I’d sacrificed my personal life for this pile of paper. Yet within days of having held that very first copy, I’d already started drafting a proposal for what I hope will be my second title, The Food of Southern Thailand. Because that book hasn’t been written yet, and I certainly don’t want anybody else to do it.

Recipe testing with Andy Ricker at his home kitchen in Chiang Mai (left); recipe testing in Mae Hong Son (right)

Road stubble (left); my hideous but trusty research sandals (right)