As early as the 1940s, Lawry’s seasoned salt had an important place in the spice racks of black families. But as home cooks become more health conscious and interested in fresh ingredients, are its days numbered?

“Don’t mess up my meat!” my mother used to say to me with a mixture of jest and admonishment. When I first started experimenting in the kitchen around age 10 or 11, I would grab spices from the cupboard willy-nilly, shaking and sprinkling away to see what flavors I could concoct. At the time, African-American home kitchens used seasoned salt—the Lawry’s brand in particular—as the starring flavoring for meat, starches, and vegetables, and my young taste buds were eager to challenge that.

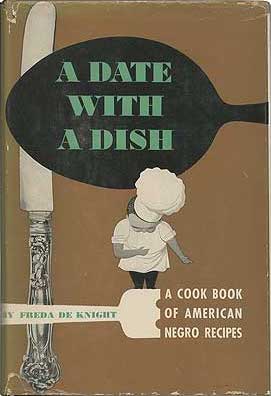

Beginning in 1938—and connected to the opening of Lawry’s The Prime Rib, a restaurant in Beverly Hills—the mixture of salt, sugar, paprika, turmeric, onion, and garlic became available in grocery stores nationwide. It’s unclear how soon after the seasoned salt made its way into the black culinary canon, but Ebony food editor Freda DeKnight’s 1948 cookbook A Date With a Dish: A Cook Book of American Negro Recipes includes “season salt” as one of the “Basic Spices and Herbs” in its “On Your Pantry Shelf” chapter.

The original Beverly Hills location of Lawry’s The Prime Rib

When it comes to the question of why seasoned salt came to be so popular within my community, there are no concrete answers. “One of the hallmarks of African-American cooking is more intense seasoning, so I can see the appeal of a flavored salt,” says Adrian Miller, the author of Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine One Plate at a Time. As for retail products, Charla Draper, Ebony’s food editor in the mid ’80s and a past contributor to a Lawry’s cookbook, told me that “the blend of herbs and spices in one jar gave African-American cooks the opportunity to buy one item containing several herbs and spices, thus being both convenient and economical.”

Lawry’s, somehow, enjoys a special status within the African-American community. Play Kanye West’s “Good Life” at any cookout, house party, or family reunion and listen to the crowd of voices rap “Lawry’s!” in unison when the song reaches the bridge. “They were an early advertiser in Ebony magazine, which gave a boost to Lawry’s popularity,” reasons Draper. More recently in pop culture, after exclaiming her preference for the brand while teaching Ellen and Oprah how to make her collard greens recipe, Tiffany Haddish was gifted a personalized bottle from the parent company of Lawry’s with her picture and signature “She ready!” tagline printed on the label.

Freda De Knight’s 1948 book, A Date With a Dish

Growing up, almost everything my family cooked was seasoned with the orange-hued spice blend—home fries, pork chops, green beans, barbecue, you name it. “Seasoned salt goes on just about everything that isn’t sweet,” says my mother. I associate that distinct salty, garlicky, oniony, and peppery taste with the classic soul food flavors I know and love.

Although Beyonce’s “hot sauce in my bag” might be the more famous refrain when it comes to salvaging flavorless plates, seasoned salt is another tool for adding color to beige meals while on the go. “Our palates are trained toward flavor, deliciousness, and savoriness, so when we’re out in these bland flavor streets we are always trying to compensate,” says Therese Nelson, founder of Black Culinary History and a TASTE Resident. “In lots of ways we’re always in search of home.” My mother adds, “Just because you’re traveling doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t be comforted.”

However, this quest for comfort and home may be charting a new course. Given the high prevalence of hypertension within the black community, many are seeking to reduce their sodium intake. “As my grandparents were aging and their health became an issue, they moved away from seasoned salt and went to a lower-sodium diet,” says Nelson.

Another health consideration is sugar, which is used in most commercial seasoned salts. It is contained in both Lawry’s—as the second ingredient listed—and Morton Season-All, which together account for approximately 80 percent of seasoned salt sales in the U.S. “The sugar is that addictive element people don’t think about,” says Nelson. I remember a cousin during our youth who would cover her plate with it, so much so that even at a young age I was concerned for her arteries.

These days I have all but eliminated the use of seasoned salt in my cooking. Not because of any particular health concern, but simply because ditching the preportioned spice blend in favor of individual containers of its components gives me more control over how peppery my ribs are, or how much garlic is in my green beans. All the same, Lawry’s still occupies a spot on my mother’s spice rack. Vestiges of this culinary upbringing show themselves from time to time—mostly during trips home while preparing fried chicken or boiled cabbage for my family—when I’m seeking the comfort of that familiar taste that’s so linked to my roots.

Between a growing interest in health and becoming more adept cooks who want a broader spectrum of and more control over flavor, I wonder how long Lawry’s hold over the African-American palate at large will continue to endure. But Miller offers a potential caveat to the shifting culture: “Veganism is one of the hottest trends in soul food, and from personal conversations with chefs, they’re using more flavored salts.” African-Americans’ relationship with seasoned salt may still have a good amount of life left in it after all.