Tea is consumed all over the world, but only in the U.S. has it been so equated with femininity that some companies try to profit from the idea that drinking it makes you less of a man.

The website for Ekön, “the first ever functional tea line designed for men,” is built on a premise and a promise.

The premise, according to its About Us page, is that prior to 2017, the year of Ekön’s founding, “there weren’t any teas designed for men. Their palate, their lifestyles, and their image were left alone to suffer.” Tea, it states, “isn’t considered manly in the U.S.”

The Ekön promise? Loose-leaf tea that provides men with the hitherto unavailable option of drinking loose-leaf tea “without the stigma, the embarrassment, or the feeling that you’re less of a man.” Ekön’s five teas come with butch names like Clean Machine, Pound Hacker, and Dayholic, ingredients “that benefit the male body,” and flavors designed for “the man’s palate.” The company’s Instagram feed is populated with pictures of virile male humans exercising, staring at mountain ranges, doing this, and meditating.

The jokes more or less write themselves. But even if Ekön’s messaging leaves something to be desired, the impetus behind it isn’t all wrong. In the U.S., tea has been coded as feminine for the better part of the last 150 years, despite the fact that in just about every other part of the world where it is consumed, it’s simply another beverage to be enjoyed by men and women alike. The question of why this is, exactly, is one that has preoccupied tea importers and salespeople going all the way back to the latter part of the 19th century; Ekön is just the latest in a long line of companies trying to answer it through gender-based marketing.

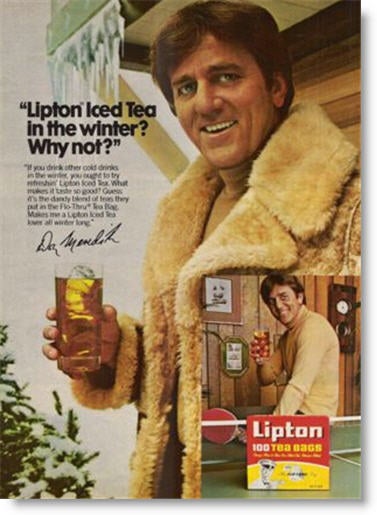

“Every generation would say, ‘Now we’re going to capture the male market,’” says Erika Rappaport, a history professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who has written extensively about the history of tea. “They’d have lumberjacks or football players drinking tea, and it never changed anything. And then the next generation would do the same.” Iced tea, she adds, was actually born of the industry’s frustration with tea’s feminine image; during the first half of the 20th century, it was marketed to men as a refreshing drink to enjoy on summer weekends. “They said, ‘Obviously this hot tea thing isn’t working—we need to try something else,’” Rappaport says.

One theory behind the American gendering of tea lies in the early-20th-century proliferation of tea rooms, which were run by and largely for women, often sported doilies and pink decor, and served the kind of dainty, sugary foods that were likewise coded as feminine. Another theory points to the female-led temperance movement, which promoted coffee as an alternative to alcohol for working men, helping to brand it as masculine. Around the same time, during World War I, tea producers in India and Ceylon (now known as Sri Lanka) pushed for contracts to have tea served in schools and factories in different parts of the world; they weren’t successful in doing so in the U.S., but the coffee industry was.

“Ultimately, if you don’t have working men drinking a beverage, it has this funny class connotation,” says Rappoport. “There was market research in the U.S. in the 1950s that said not only is [tea] feminine, it’s snobby and aristocratic.” In 1951, as she writes in her book A Thirst for Empire: How Tea Shaped the Modern World, a market researcher named Ernst Dichter surveyed men and women of all ages and reported that 72 percent of them “believed tea was for women.”

If coffee in the U.S. became known as a working man’s drink, complete with the manly nickname of joe, then tea continued to be commonly associated with tea parties, the English, and gossiping women, no matter its complexity or, for that matter, the comparative strength of its flavor or caffeine content. This is, admittedly, an extremely broad characterization, but it’s one that has made it possible for a company like Ekön to exist and also inspired some American men to question why their compatriots write off tea as “wimp juice” or subscribe to the notion that “real men don’t drink tea.”

The inspiration for Ekön came from all of the functional teas being marketed to women. “There was nothing talking to men,” says Jose Benacerraf, who founded the company with David Lustgarten. “If women can talk to women, why can’t men talk to men? You’re not excluding anyone; you’re saying to a segment of the population who hasn’t been formally invited, ‘Hey, come and drink.’”

But do men really require a formal invitation to drink tea any more than women require one to drink coffee? “You don’t,” Benacerraf concedes. “But it’s like when you get a flyer that says come to a store. Kmart and Walmart have always been there; if you get a flyer, you consider going. The fact I’m inviting you doesn’t do anything bad. I don’t see anything wrong with it.”

Maybe there is a population of men that does need an invitation to feel that it’s OK to drink tea. And maybe it’s all as meaningless as Ekön’s name, which Benacerraf and Lustgarten made up because they wanted something that would sound “masculine and modern,” Benacerraf admits, and Ekön “sounded OK and was available.”

For her part, Elena Liao has never really looked at tea through the lens of gender. As the co-owner, with her husband, Frederico Ribeiro, of New York’s Té & Company, she spends much of her days watching men and women drink tea. She’s seen plenty of men geek out about it, and plenty of women use her tea room as what she calls a “forum for conversation.” But for Liao, our attitudes about tea aren’t a function of gender. Instead, she sees a larger issue. “American culture,” she says, “doesn’t really celebrate tea like the rest of the world does.”