![ARTICLE[63]](https://tastecooking.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/ARTICLE63-2000x1123.jpg)

A visit to the hus that René built presents 18 meticulous plates of food, with a few lingering questions to wash it all down.

I saw a tweet recently that stuck with me. “If smoking weed makes you paranoid and anxious, that’s because you approached the joint with impure thoughts and a heavy karmic debt,” it read. You could say the same thing about Noma. Its five-hour tasting menu will not cheer you up like a basket of hot garlic bread or a Tito’s martini will. And if you walk through those greenhouse doors and wince a bit while ducking under a nine-inch cucumber ripening on the vine above your head, the next five hours of your life aren’t going to be happy unless you really like getting drunk on cloudy orange wine and creating content. Lucky for me, I like all three. You can’t manipulate an evening at Noma, the legendary Copenhagen restaurant that is set to close at the end of 2024; all you can do is prepare yourself to be manipulated.

I never thought I’d have the opportunity to visit the hus that René Redzepi built. The price (for two, the Amex statement hits $1,541.77 and comes with some wine, but not pairings), the location, and the waiting list (more than 10,000 names) make most people resent the place without ever visiting—including me. As I walked past the wood-grained induction kitchen on a recent summer evening, the entire staff, Redzepi included, stood en garde and yelled out a greeting not unlike a sushi chef’s “Irasshaimase,” the first of many Japanese-influenced touchpoints to come.

This is where I had my first conspiratorial thought, likely tinted by watching the 2022 film The Menu. As René looked into my eyes upon my arrival, I wondered what role I would play in this production, how much space I’d take up in the dining room. Have they done any research on me—my name, my mug shot, and my extracurricular activities on a page in the night’s dossier? Do they know how many times I’ve made pine cone jokes on my show, or how many reindeer-penis-related memes I’ve double-tapped on social media? You assume he has no idea who you are, but part of you hopes he does.

In reality, I’m just one of 84 forgettable diners per sitting, eating 18 meticulous plates and washing them down with hundreds of dollars’ worth of plum wines, lemongrass teas, and house-poured waters. Like with any exclusive club, the general rule is that the crowd worsens as the years tick by, and it’s no surprise that René is shutting down next year; I’d pull the rip cord too, mate.

I imagine the edimental salad days, back when gourmand freaks with open minds and food writers craving the next big thing lined the reservation book. I got a feel for the evening’s clientele with a welcoming cider: crypto bros, ponytailed tech virgins with bottles of añejo for the chef, and their TikToking wives along for the clout-chasing ride. I’m sure these folks like eating food, but do they really deserve to eat here, the Vatican for the global food bro?

Exclusivity isn’t always bad, so long as you can exclude the right people.

René wore Yeezy slides and an understated post-rave bracelet as he chatted up a few VIP tables longer than necessary. I tried taking a photo of the first of our 18 vegetarian courses, delicate sashimi rectangles of a king oyster mushroom’s tenderloin, crosshatched like a squid steak and served with a dipping sauce of hazelnut milk and droplets of some cool oil. But the exposed lightbulb above our table seemed to interfere with my iPhone’s camera, confusing its focus. I had hoped the dining room would be outfitted with a photo-blocking sonar signal, forcing everyone to focus on the meal and not document it, but it worked fine in 0.5 mm mode.

You can’t manipulate an evening at Noma, the legendary Copenhagen restaurant that is set to close at the end of 2024; all you can do is prepare yourself to be manipulated.

My wife was convinced that each rectangle of mushroom had an ant underneath, like how a dot of wasabi would be hidden under nigiri. I thought our server would have to disclose that the first bite of our vegetarian meal contained insects, but I hoped she was right.

Next came the best seeded cracker I’ve ever eaten. The “miso crisp” almost tasted fried, but I knew it wasn’t. On top was a flower of golden beet petals, which crumbled to a mess with one bite due to user error. A brunoise of beet would probably eat much better, but that wouldn’t be very Michelin. This cracker from the heavens was served in tandem with a rosebud filled with some cream and a sliver of raspberry, cut on the bias. The sliced berry reminded me of a tiny salmon steak, and the flavor of rose took the back seat, as it should. I thought of how we typically taste rose in liquid forms, like truffle and truffle oil. I reminded myself to savor the rose while it was still alive and breathing, just as I would with fresh truffle.

Next was another two-parter, a long dark husk of ramson, the European cousin of the ramp, that looked like a drawing of a razor clam. Inside was a kojied barley cake, cooked on the grill and basted with various umami-rich sauces. I enjoyed how our server simply named this dramatically altered gothic husk of a dish a “barley cake.” It looked like one of those prehistoric fish you only find in the ocean’s abyss. Some food runners are more long-winded than others. When a dish’s description feels too cryptic, I pester them for more information. We’d never know if they’re hurrying back to their station as they gladly shower me with nerdy details after some prodding.

The chef comes closest to mimicking meat with this dish, which tastes like the most extraordinary barbecue tempeh slider I’ve ever had. I slowly savored each tiny bite, fantasizing about a proper-size patty of this cake, basted in fennel pollen barbecue sauce over Japanese coals and plopped on a Martin’s potato roll with Kewpie coleslaw. (Chef, please run a special at POPL.) Alongside this stunner was the infamous pine cone. It was an adorable cone, one of the thousands I saw while walking around Frederiksberg, skewered on a pruned pine twig with medicinal leaves on the kebab. It tasted like . . . a pine cone, and the leaves tasted like the A5 wagyu of cactus, a flavor I have never enjoyed. It’s probably fun to prep these twigs with a pair of bonsai scissors.

Next, a whole potted onion hits the table—that is, an onion serving as a soup’s vessel. Remove the allium’s top, and you’ll find an onion soup portioned into two extraordinary spoonfuls of congealed caramel. Imagine a French onion soup, with its deep flavor, suspended in a gel, maybe agar, with five beechnuts and a dollop of loosely whipped cream. The rich flavors of reduced onion, balanced with the restrained brightness of plain cream, were just stunning—it was my wife’s favorite savory course of the night.

Our server encouraged us to avoid eating the onion vessel, and I wondered why. Surely it was sanitary; this was the most perfect onion I’d seen. Maybe a bite of raw onion could disrupt the delicate dance so far. Nevertheless, I took a small taste from one of the protruding scallion tops; it was good.

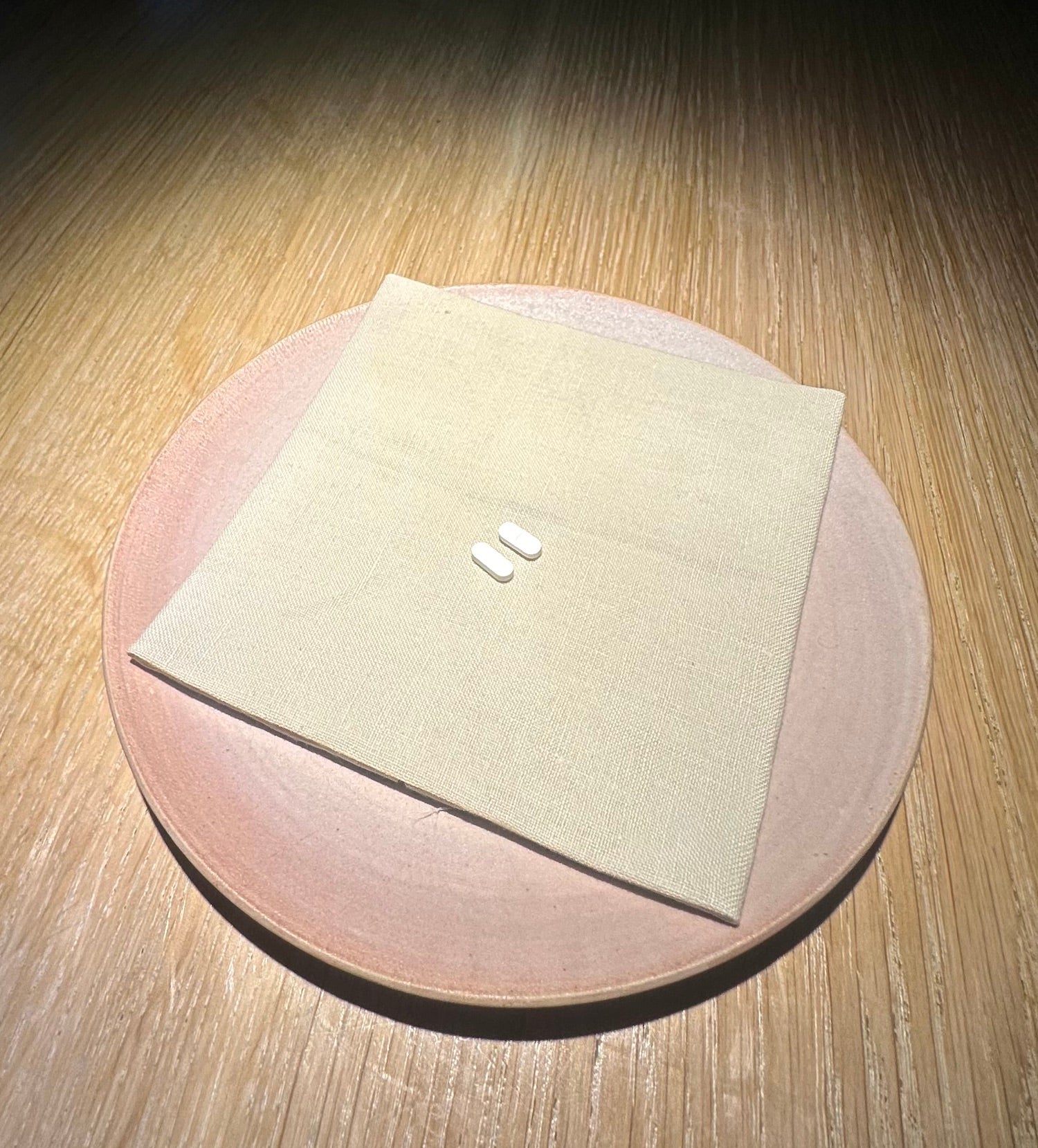

My wife began showing allergy symptoms, and I asked our server if they had anything to help. Less than a minute later, he produced two pills, thoughtfully plated. I had the opportunity to post a cryptic photo of Noma serving drugs on my Instagram, which was nearly worth the price of admission. The Zyrtec course came at the perfect time, just before Noma’s most pollen-forward offering: the flower soup. This was the first point in the meal where I tried to understand a dish’s goal beyond the fact that looking at a kaleidoscope of various local flowers is nice. The dish relied heavily on the “tomato water” that served as the soup’s base, probably because tomatoes taste better than most flowers. Nobody’s eaten a jackfruit banh mi and thought, “You know what would knock this hoagie out of the park? A purple flower that tastes like unripe water.” This is my logic.

I’d like to think Noma considered this a challenge: making a photogenic but flavorless garnish taste not only excellent but essential to the overall dish. Some flowers were chewy, and some dissolved instantly. Each bite was not wholly different, but it was different enough. Tails of moving flavor lasted long after swallowing.

At this point in the meal, I realized they knew I was left-handed. That delight carried me through our two least favorite courses. One was a spoonful of perfect peas and pumpkin seeds held together by a blackcurrant leather wall, the way you’d wrap urchins in seaweed. The other was a charred eggplant pile with a fun Japanese peppercorn that had a subtle Sichuan-like numbing effect. Some foamed Danish cheese and jade tea surrounded it all. The taste of the cheese was lost, but I loved how the jade flavors panned long and wide while the peppercorn sat up front. Maybe I don’t love eggplant. I understood why these two plates went together, but they didn’t progress what was happening in our mouths so far.

Next came a clove of young confit garlic wrapped in a half-moon dumpling-like millet parcel. This was served atop a sauce resembling semen in both color and viscosity, rained upon beautifully with snipped marigold leaves. I loved the millet skin dumpling. The garlic inside tasted raw, unlike a typical confit, where it’s melted down and sweet with oil. After asking for more preparation details, our helper said the garlic was actually “confited” in milk. If this clove was indeed milk-poached, it must have been done for ten seconds, tops. I made a joke about them cooking the clove “rare” that landed as well as a pine cone on the palate. Regardless of the semantics, I enjoyed the dish.

“Nordic yuba and beach greens,” or milk skin and green pepper, came and left without much excitement. A Scotch quail egg tempura with pumpkin paste and something like a fennel XO sauce impressed us with how amazingly brittle the bread-crumb-less crust was that shattered in our mouths while keeping the tiny yolk soft and light. Next was another standout dish, young green rice from Japan with green tofu made from mostly soy but a little cow’s milk. How much cow’s milk can you add before tofu turns into cheese? Wasabi blossom added the perfect gentle kick, and it all sat lightly soaked in the same dashi found in the gift shop.

Next, a crudités of the day’s best leaves, berries, vegetables, and other bits, all sliced uniformly thin by hand with a “special knife from Japan.” This was a master class in knife work sitting atop a puddle of more tomato water and miso. Watch for glimmers of “tomato water and miso” next month on your local safe-space dinette’s menu.

I loved that this course tasted like everything, which set us up for the flavor-honed final savory course, grilled king oyster mushroom—the outside part this time. It was a call back to course one, basted with enough umami to turn an engine over and covered in black truffle. These slices weren’t shaved from above in a “make it rain”–style tableside show, with its inevitable anticlimactic clumping, but instead purposefully placed in a way I found to resemble a handful of butterflies on a log—fundamental meat mimicry at its highest level while still keeping it natty.

After this, our server brought a bottle of Japanese plum wine we were meant to drink with our dessert courses. In this seventh-inning stretch between savory and sweet, I spied the VIC two-top next to us slathering butter on bread and having a great time doing so. This reminded me of a message someone had sent me on Instagram the day before, telling me there are free refills on Noma’s bread and butter—something we had not yet taken advantage of once. Was it an earnest tip or an easy DM joke?

Riding high off a glass of cloudy orange wine, I flagged our runner and asked if the bread course our neighbors were loving was in the cards for us, and this inquiry seemed to alter the future of our evening. I felt like Violet after grabbing a sample of gum from Wonka’s factory, about to be sung out the door by Danish Oompa-Loompas. To break the three-second-long awkward silence, I asked, “Did I just ruin the flow?” Is it an amateur move to ask for some bread after eating 14 courses of the best food on earth while awaiting the dessert climax? Was this the Danish version of asking for a side of ranch in Naples? He thought about it momentarily and said something polite and perfect as he quickly evaporated. Seconds later, two ninjas silently removed our dessert course spoons. I looked at my wife and said, “We’re fucked.”

Sourdough hit the table with softened, salted, and perfectly yellow butter. Our person brought Champagne to pair it with. Were these bubbles a gift from the somm, or a pound of flesh from the kitchen for the bread-and-butterfly effect we had inflicted on an already complicated dance? Our server asked how we liked our bread. I said, “Of course, it’s amazing. Bread, butter, and Champagne, how could anything compare?” I then realized how this could have been taken negatively by a restaurant staff that had spent days growing mold for me. Imagination brought to life thanks to the tireless work of a hundred geniuses, bested by something that comes complimentary at the Cheesecake Factory.

Worrying that I had struck an off-key note, I asked how they made the bread. He said they don’t make it in-house. It’s from Hart, the bakery of former baker Richard Hart—recently lusted over by Marcus on The Bear. I said, okay, but the butter is undoubtedly churned on-site, yes, chef? A brief pause, followed by a no. I had told this lovely server that our favorite thing we ate all night at the world’s greatest restaurant was the one thing their chefs didn’t make. Does asking for bread at Noma wake you up from the dream, or does asking for bread unlock the next level of Noma? The answer was yes.

Our big bottle of plum wine returned, and dessert began with berries and cream. The blue, black, and red currants all looked nice, with some familiar friends and some Scandinavian offerings yet to make it stateside. The cream is flavored with woodruff, giving a forest-like undertone to the dish, perhaps inspired by the branches and leaves from which these berries were plucked.

After that came the plate that broke my wife’s brain. It was an ice cream sandwich mimicking onigiri, the handheld Japanese rice ball swaddled in a seaweed sheet. The triangularly molded ice cream is flavored with a fernet-like Danish bitters and wrapped in a white sheet. The fitted sheet is grown in this specific triangle shape in a temperature-controlled incubation cabinet. The nori diaper had been replaced by blackcurrant leather. I wished they had found something with the crispy snap of toasted seaweed rather than the sweet, chewy fruit leather. I suppose blackcurrant leather is fine, but I was surprised by how often such a 2009 ingredient appeared on my plate. This dessert, however, still haunts my wife a week later.

Much like our drinking water, a beautifully floral digestive tea is suggested to us as if it’s a gift that won’t appear on our bill. It was nice. Our final bite was a marigold flower, broken down and reconstructed with chocolate underneath and a gel on top with dried and powdered berries. I liked how elegant the top of the colorful flower was and how rough the chocolate was beneath it. Now, off to the parlor for six tiny glasses of schnapps to prepare for the sting of the final bill. Our server was kind enough to give us a tour of the kitchens while we waited for the cab he called for us to arrive.

Is it an amateur move to ask for some bread after eating fourteen courses of the best food on earth while awaiting the dessert climax? Was this the Danish version of asking for a side of ranch in Naples?

A few closing thoughts: The Venn diagram of people who can afford to eat at Noma and the people who deserve to eat at Noma is small. Did they make the trek because they were dying to go or simply because they could? You can’t judge a book by its cover, but Noma’s elite setting pushed me to try. Or maybe that is the whole point of the meal—that high is what you pay for. Well, that and spending hours tasting things you’ve never tasted before. Anyone can smash a burger.

I found it challenging to be present at Noma because the anticipation of going to Noma is sweeter than any fruit leather you’ll eat while you’re there. And you don’t know it while you’re in the restaurant, but to me, the natural gift of Noma is how you feel after ingesting a perfectly calibrated tasting menu full of hundreds of ingredients all grown from the earth very near where you’ll sleep that night. It’s like earthing with your mouth instead of with your feet. You feel an electric connection to the world around you for those brief hours of digestion. Like a psychedelic journey, it’s never perfect, but if you approach it with pure thought and overflowing with karmic credit, it’s a trip worth taking.