Activist and Soul Fire Farm founder Leah Penniman believes that our food system can learn a lot from the historic innovations of Black farmers.

Early last year, when COVID-19 began to tear through the United States, creating fissures in our food systems and wreaking havoc on our grocery stores, Leah Penniman knew exactly what to do. The founding codirector of Soul Fire Farms, located in Petersburg, New York, had spent the past decade developing sustainable ways to produce and deliver fresh fruits, vegetables, eggs, and other groceries directly to the doorsteps of communities in nearby Albany.

For many of the people who receive these Solidarity Shares (Soul Fire Farms’ sliding-scale version of a CSA box), the deliveries already filled in the gaps in a defunct system that left their neighborhoods in a state of food apartheid—a population devoid of nutritious, fresh, accessible food. These shares offered an alternative to our existing framework for getting groceries, while paying tribute to Black innovators like Dr. Booker T. Whatley, the Tuskegee University professor who was an early advocate for community-supported agriculture in the early 1900s.

As Penniman is quick to point out, white people are often credited for inventing progressive-minded farming practices that prioritize sustainability and equity. Unsurprisingly, there’s much more to the story. In her 2018 book, Farming While Black, she sets the record straight on some of these movements. Organic farming wasn’t invented by 1960s environmentalists in California—it’s a millennia-old African-Indigenous system. Regenerative agriculture isn’t an invention of the 21st century. Dr. George Washington Carver started advocating for it in the late 1800s. Recently, Penniman and I had a conversation about what else can be learned from the legacy of Black farming, in a future where climate change will increasingly collide with racial inequality, refugee crises, and, yes, pandemics.

You’ve had quite the year. How different has 2020 been at Soul Fire Farm from the last couple years?

Oh my goodness! Well, in some ways, we were really blessed to be in a position where the offerings we had for community were and are right in alignment with community need, even through multiple pandemics. We do doorstep delivery of fresh food. We build gardens for people in urban spaces. We give access to that food sovereignty. We train folks in how to grow their own food, and we train farmers who had already planned to do some of this online through a video series and a webinar series. So, in some ways, it was a continuation of the sacred work we already do—with even more need, and even more folks who needed that food and needed those gardens. And even more folks who wanted to learn to grow food.

And in other ways, things certainly changed. Most notably, kind of the pivot point of our year are these weeklong farming immersions where people come and learn everything from soil to seed to harvest to market in these cohorts—and, needless to say, we couldn’t gather folks from all across the country and have them snuggle together on the land in a time of a pandemic. So we postponed, and the accepted cohort will come in the following year, fingers crossed. And then, additionally, we did a series of these bilingual how-to farming classes online, so that was a pretty big shift. We had to learn quickly how to make it work, and how to make it right. And we found the blessing in it, in terms of, for one, its compatibility with farm life (you can pop in on a Zoom and pop back out to the strawberry patch without a lot of travel), but also accessibility. And we have alumni in the UK, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Canada, and they were able to come to our programs that would have been really difficult in the past. So that’s a summary of 2020 being different.

COVID obviously shed some light on all of the ways that the food systems are broken in our country. Reading your book, I can’t help but think that Soul Fire Farm was pretty ahead of the curve when it comes to this, especially when it comes to your philosophy about accessibility of food, and the importance of delivering to people’s doorsteps. What can the rest of the United States, and the rest of our food systems, learn from COVID going forward?

Well, something really powerful about COVID is that it laid bare the cracks in the industrial food system. What I mean by that is, we get a lot of criticism as small, regenerative agriculture, that “It’s not efficient, how can you scale it up?” But one of the downfalls of a super-efficient food system is that it is not resilient or flexible when, suddenly, the schools are closed, and the restaurants are closed, and distributors are used to serving that particular market. They don’t have the distribution channels, the containers, or the relationships to pivot that food to where it needs to go. Whereas what we saw with our local food community was that all of the farmers, almost overnight (within 48 hours) had set up online stores, no-contact drop-offs, CSAs, people bringing food to elders who needed it.

So there really is a resiliency within the local food system that I think we need to pay attention to—because these natural and unnatural disasters are not going to lessen as we go forward. We’re in a time of climate chaos, where we can expect wildfires and hurricanes and disruptions. We’re in a time of population growth, and we can expect pandemics, and we can expect refugee crises. All of this will increasingly be part of life. So we need to have food systems that are resilient. I think that was one of the big lessons.

The work is essential, but not the worker, is the viewpoint of mainstream society.

I think another big lesson is that we need to pay attention to what we mean when we say “essential.” Because there’s a lot of talk about “essential” workers, but does that really mean that the lives of the people who do that essential work are considered sacred and valuable and worthy of protection? I don’t think so. When you look at the number of COVID outbreaks at meatpacking plants, food processing plants, and among farmworkers, and the fact that undocumented farmworkers weren’t even eligible for many of these relief programs—and sometimes not even for COVID testing paid for by the government—it really shows where the priorities lie. The work is essential, but not the worker, is the viewpoint of mainstream society.

Has your proximity to New York’s state capitol of Albany changed anything about your activism? Have you had any direct conversations with lawmakers just because of where you are physically?

We don’t directly lobby, because we’re a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, so our advocacy is mostly around public education. We are members of HEAL Food Alliance, which does have a lobbying arm, so we’ll chime in on some policy initiatives.

But early on in the life of the farm, we were approached by the Albany County district attorney to see if we wanted to pilot and cocreate an alternative-to-incarceration program for adjudicated youth called Project Growth. And so, to create this program—which was a 50-hour leadership course based on the farm, after which the young people, when they graduated, received a stipend and had their records wiped clean—that required an act of legislation. So we did obviously advocate for that legislation to pass, so that we could run the pilot program, which has since become an actual program that the county runs, but more with nonprofits right within the Albany area.

But, you know, we show up! We show up at the rallies for Black Lives Matter and other topics that are essential to our mission. But we don’t do a lot of direct lobbying.

You write about the concept of Ujamaa, or cooperative economics, as a basis for Soul Fire Farm’s CSA program. I think this is a question for a lot of activists, but how do you go about reconciling this economic model with the capitalist systems we live under? How do you carve out space for thinking differently about this?

Yes, Ujamaa cooperative economics. That’s such a good question, and obviously, we don’t have the answer. But in some small ways, like with our Ujamaa CSA, which we now call Solidarity Shares, there are a couple ways that we push back against a capitalist framework. One of them is that, instead of charging a price that yields a profit on the market, we ask people to pay whatever they can afford, and we use trust and relationships, and an honor system around that, and folks can pay down to nothing.

Another way is that it’s relational rather than transactional. The members of the Solidarity Shares, many of them have been with us for years, and we have personal relationships with them of mutual concern and caring, so we’re growing that food for people we know, and they’re receiving that food from people they know. Which is really different from going to Walmart to get your food and not having that relationship!

And then, I think, zooming out a little bit in terms of how this whole project relates to that, a lot of the funds for the initial stages of the project came from a cooperative lending organization, similar to a susu, which is a Caribbean women’s lending society—a proto credit union. Essentially, a group of friends or community members put in a certain amount of money regularly as dues, and then they lend each other large sums for capital projects, like building a farm or a house. So rather than a traditional bank, we actually used a susu in order to finance the original infrastructure of the property.

You write a lot in the book about regenerative agriculture practices and why they’re beneficial for the environment. I’ve been noticing the word “regenerative” on more and more labels at the grocery store. What do you make of grocery store labels like “regenerative” and “organic” in big-box grocery stores? Is it just another way to market products, or should we look out for these labels?

That’s really a good question. I think probably the hardest time I have with the current regenerative movement is that it doesn’t acknowledge its Black American founders. Regenerative agriculture was actually founded by Dr. George Washington Carver in the late 1800s out of Tuskegee University when he was advocating for cover crops, crop rotation, diversified agriculture, composting, and mulching—like two generations before and even longer before the so-called founding of the current regenerative movement. So that’s painful for us, because I think it’s really important to acknowledge Black farmers’ contributions to sustainable farming in a meaningful way. Additionally, I do think that consumer labels have a place, and unfortunately, it can be confusing to know what they really mean. I’m not familiar with what you have to do to get that “regenerative” label.

I know that “organic” has been quite diluted, and when I was working in Massachusetts at Many Hands Organic Farm and with NOFA, the Northeast Organic Farming Association, we were part of some of the lawsuits and fights to prevent the federal government from taking over “organic” and diluting it. So I was very, very familiar with that moment. It was in the early 2000s when “organic” became less meaningful. And I imagine that probably would be the trend with many labels, so we have to stay vigilant. But we do, at the same time, adhere to a couple labels. We have Certified Naturally Grown, which is a peer-to-peer organic-like certification. It exceeds organic. And then we also have a

Farming While Black came out almost three years ago. Do you have a dream next book that you want to write?

I do, actually, I’m in a contract negotiation! The next is Black Earth Wisdom, and it will be published by HarperCollins. The book celebrates the voices of respected Black environmentalists who have cultivated the art of listening to the earth and conveying the messages that the earth needs us to hear. I have some wonderful interviewees that I’ve already started connecting with, and that book will come out in 2022.

5 RECOMMENDED READS FROM LEAH PENNIMAN:

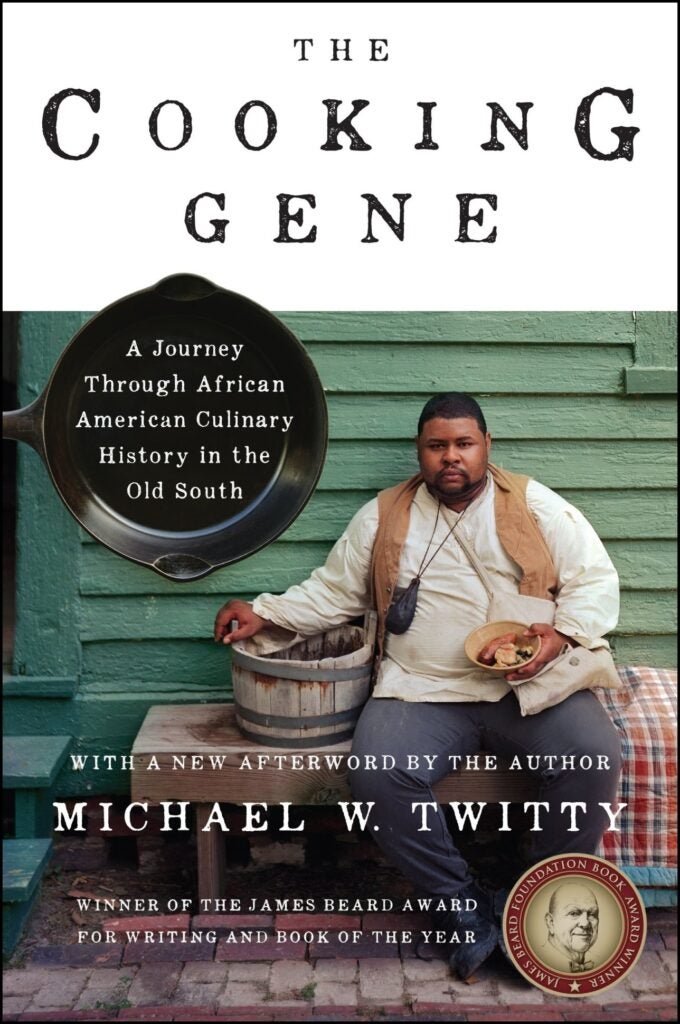

The Cooking Gene, by Michael W. Twitty

Twitty examines the South’s African American culinary history by tracing the stories of agriculture, cooking, and resilience of his own enslaved ancestors.

Working the Roots by Michele Elizabeth Lee

A collection of interviews, stories, and learnings from African American healing traditions.

Homecoming by Charlene Gilbert and Quinn Eli

Tracing the history of Black farmers from Reconstruction through the ’90s, Gilbert and Eli examine the legacy of hope in the face of enormous loss.

The Color of Food by Natasha Bowens

A collection of portraits and stories of the farmers of color who are preserving culture and community and challenging the status quo in American agriculture.

Freedom Farmers by Monica M. White

White writes about how activists like Fannie Lou Hamer used agriculture as a means of resistance and self-reliance during the Civil Rights Movement.

Futures is our monthlong series of interviews with the individuals and organizations reshaping the way our culture cooks, eats, and thinks about food. Read last week’s conversation with Omsom founders Kim and Vanessa Pham.