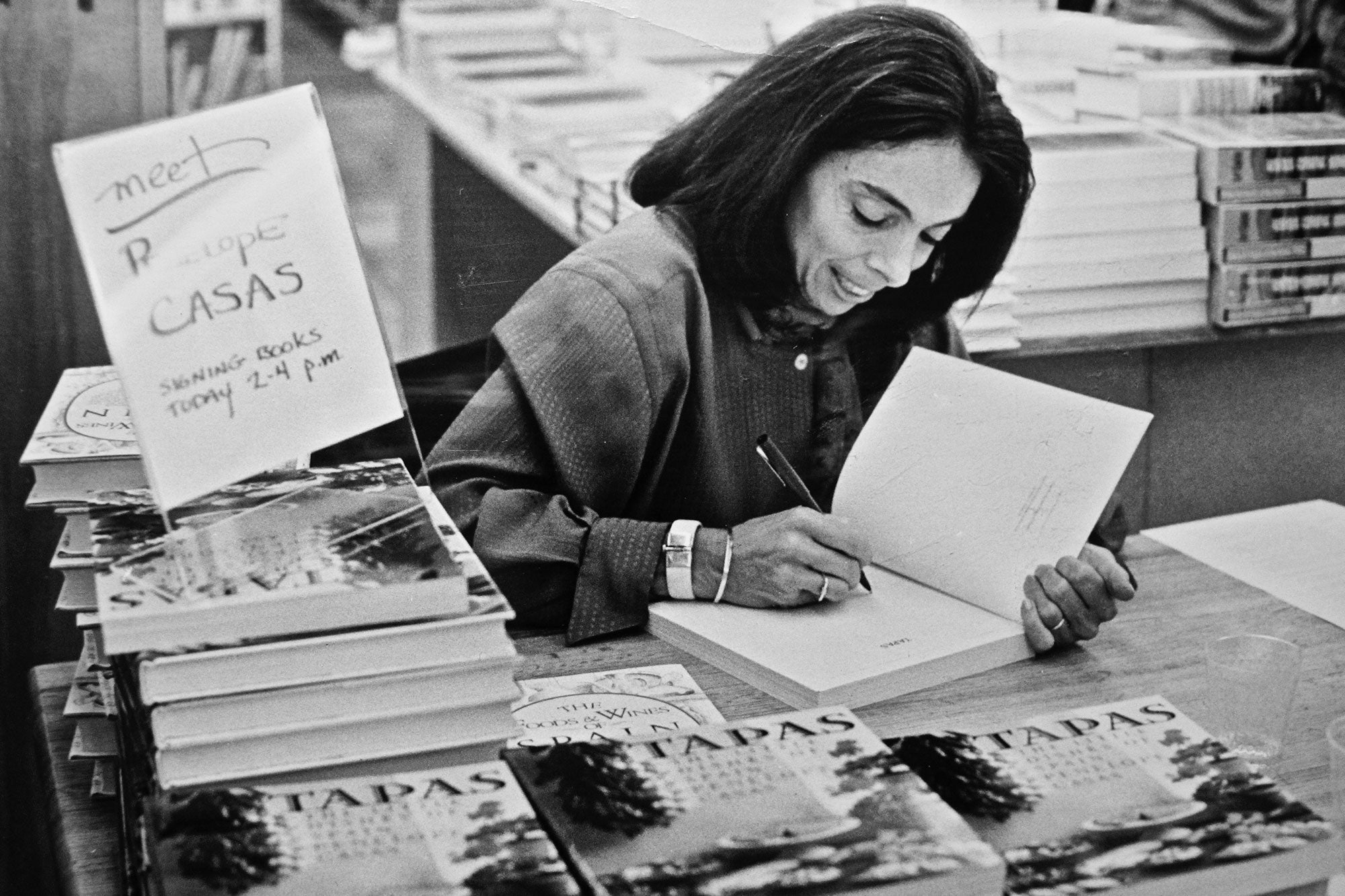

How a Greek woman from Queens taught America to cook tortilla and tapas.

In 1979, Craig Claiborne wrote an article in the New York Times about the common Spanish tapa “angulas,” or baby eels tossed in olive oil and nestled with garlic and chile flakes. Claiborne misspelled the term as “anguilas.” Shortly afterward, he received a letter of polite correction from someone named Penelope Casas, a 36-year-old woman from Whitestone, Queens. The two went back and forth in the pages of the Times until Claiborne admitted he was wrong in the face of an extensively researched, articulate letter from Casas detailing the etymology of the word and its spelling.

Casas’s husband, Luis, was determined that she not leave this correspondence as her legacy with the newspaper of record. He encouraged her to invite Claiborne over for a proper Spanish dinner. Casas, reserved and modest, was hesitant about the idea, but she eventually obliged, and Claiborne accepted.

The multiple-course dinner that took place on a summer evening in the Casas family home in Queens consisted of a white gazpacho, a specialty of Extremadura; a Spanish tortilla; quail soaked in acidic escabeche; and, appropriately, angulas. Claiborne used the dinner as inspiration for the article titled “Homage to the Varied Cuisine of Spain,” in which he playfully described the etymology of the foods he ate and reviewed the surprising combinations of ingredients he was trying for the first time. He was so impressed by Casas after the meal that he introduced her to Knopf editor Judith Jones (a titan in cookbook publishing, famous for editing Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking), encouraging Casas to write a culinary history of Spain—something that had not yet been published in English at that point.

Under Jones’s editorial guidance, Casas published her first cookbook of many, The Foods and Wines of Spain, in 1982. In its introduction, Claiborne fondly recalls the initial dinner he shared with Casas as “one of the most memorable meals that I have experienced in nearly a quarter of a century with my newspaper.”

Claiborne fondly recalls the initial dinner he shared with Casas as “one of the most memorable meals that I have experienced in nearly a quarter of a century with my newspaper.”

Over the course of the next 30 years, Casas wrote eight cookbooks that span the entirety of Spanish cooking. A 1985 Publishers Weekly review credited her with continuing “to do for Spanish cooking what Marcella Hazan has done for Italian.” In Spain, she was awarded the National Gastronomy Prize, the Order of Civil Merit, and the title of dame of the Order of Isabel la Católica, among the highest decorations a non-Spaniard can receive. Colman Andrews, founder of Saveur magazine, called her “the American who knows all about Spanish food.”

In her many cookbooks and writings for publications such as Food & Wine, Vogue, and the New York Times, Casas revealed the intricacies of regional Spanish cuisine, which was historically neglected and misunderstood in America. Despite her work in introducing and popularizing Spanish food among American home cooks, her name has been fairly unknown after her death at age 70 in 2013.

Growing up in Queens as the daughter of Greek immigrants, Casas was an unlikely candidate for introducing the United States to Spanish cuisine. But in 1962, while studying abroad in Madrid, she fell in love with the food, and with Luis Casas, the 25-year-old son of her hosts, who was sent to pick her up from the airport when she arrived.

“I look and see this nice, beautiful girl with beautiful eyes with a nice, green summer dress next to a piece of luggage,” Luis tells me. He asked if she was Penelope. She replied, “Yes.” The two went for a drink, and soon after, they started a relationship that lasted 50 years.

Casas quickly adapted to the Spanish custom of eating lunch at 2 p.m. and dinner at 10 p.m., spending long hours conversing over never-ending courses of cold fish timbale doused in homemade mayonnaise and “poor man’s potatoes” simply adorned with green peppers, garlic, and onions.

When she and Luis weren’t combing through the stretches of tascas (tapas bars) in the streets of old Madrid, staying out until 2 a.m. despite school in the morning, Casas was in the kitchen with Pilar, the chef and nanny of the Casas household, and Clara, Luis’s mother. Casas helped as they prepared lunch, scribbling notes in one of her little notebooks. Luis and his family still have her nearly 350 notebooks filled with notes on Spanish history, art, and culture.

Eventually the summer ended, but Casas returned to Spain each summer that followed. In 1965, she graduated from Vassar, eight months pregnant with her daughter, Elisa, and moved to Madrid, where she and Luis lived for five years until permanently moving back to Whitestone, Queens. Even then, they regularly enjoyed their summers traveling through the Spanish countryside by car.

Luis and his family still have her nearly 350 notebooks filled with notes on Spanish history, art, and culture.

With one of her notebooks as her companion, Casas often asked for the recipe when a particular dish appealed to her. In The Foods and Wines of Spain, she recalled the time her family stopped at El Galán in the coastal southwestern town of El Puerto de Santa María. After eating calderata de codornices (potted quail), Casas asked the waitress for the recipe.

“Consumed by giggles, the waitresses, all daughters of the cook, took us to meet their mother in the kitchen,” Casas wrote in her book. “She in turn was astounded that visitors from New York were praising her cooking and requesting her recipe.”

Back in New York, Casas tested the recipes in her own kitchen. “Every single recipe in those books she would make one or two or three times until it was right,” her daughter, Elisa, tells me. She cooked elaborate meals, experimenting into the late hours of the night, keeping with the Spanish tradition of eating dinner at 9 p.m. or later.

In the early 1980s, the United States misunderstood Spanish cuisine, recognizing it only as a handful of dishes. As R. W. Apple Jr. admitted in his 1982 New York Times article entitled “Spanish Treasure,” he had “confidently dismissed Spanish cooking as an oily mediocrity, a compound of gazpacho and paella and excessively heavy red wine.”

Casas’s work in demonstrating the breadth of regional Spanish cuisine became imperative. When The Foods and Wines of Spain was published in 1982, it was immediately met with praise by Mimi Sheraton of the New York Times, who called it “one of the best works on Spanish food ever presented to the American public.”

Gregory León, chef of Amilinda, a Spanish and Portuguese restaurant in Milwaukee, credits the book with inspiring his renditions of croquetas, salmorejo (a classic Andalusian soup served cold, based on puréed tomatoes and bread), and vinaigrettes. “It’s still one of my main references that I go to once a week,” León says.

By the mid-2000s, the United States was growing warmer to the complexities of Spanish cuisine, but Casas’s work remained unfinished. Even with seven cookbooks under her belt, she had one final project to complete. It would be “the broadest and deepest collection of Spanish recipes ever published,” says her editor, Linda Ingroia, of the book, 1,000 Spanish Recipes, published in 2014.

“Only someone like Penelope, as experienced in cooking the cuisine, and who could conduct hundreds of interviews with local cooks, chefs, and experts throughout Spain, could collect such an expansive recipe compendium as well as the background stories and cooking secrets that keep such a comprehensive book so personal and accessible,” Ingroia says.

In the seven years it took her to compile the extensive collection, Casas became sick with leukemia, but she remained entirely dedicated to finishing the manuscript for her most encompassing work on Spanish cuisine.

“She finished the last chapter of the book on a Tuesday and she was radiant, happy, and proud of herself for having completed the most extensive book project of her career,” Luis wrote in 1,000 Spanish Recipes. “She died five days later.”

Now, six years after her death, Casas’s books remain as relevant as ever. Whether she was writing about the oldest bakery in Madrid, Antigua Pastelería del Pozo, where one could spot the bakers from the street patting and rolling dough, or about Señor Suso of Bar Suso in Galicia’s Santiago de Compostela, a man who was always eager to show off his postcard collection to guests, every recipe tells the story of a side of Spain most of us have never seen.