There’s one goal at celebrated New Orleans sandwich counter Turkey and the Wolf: “Make the store shit taste good.”

How to Dress Up Grocery Store Food. That’s what a cookbook from the crew behind New Orleans’s absurdist, bonkers-delicious, insouciant little-sandwich-shop-that-could Turkey and the Wolf could, or would, or should be called. Or so says its chef-owner, Mason Hereford. And I agree. It’s a crass and maybe even slightly reductionist title. Still, it burrows to the hungry heart of what makes Turkey and the Wolf the singular creature it is.

I have been eating at the corner shop in the Irish Channel neighborhood since it opened in August of 2016. The flavors and textures have always been big: potato chips cresting a fried bologna sandwich; Duke’s mayonnaise slicked over every inch of bread in sight; fried chicken skin jutting from the top of deviled eggs; an everything-bagel spice mix blanketing a gonzo wedge salad. Somehow, though, there was finesse to the onslaught. Largeness and elegance, neck and neck.

There was much immediate goodwill shined on Turkey and the Wolf and its battalion of veteran restaurant people, especially from other New Orleans hospitality professionals. Then, in September 2017, Bon Appétit named the wee shop with the streetside patio and brick-red facade the single best restaurant in the country.

See, Bon Appétit got what we in New Orleans understood instantly about Turkey and the Wolf. This is food that is profoundly gratifying. Food that is more or less what you always want to eat. Exactly. All in a freewheeling order-at-the-counter environment, where bright retro diner tables, mismatched vintage plateware, and kookily named cocktails like Be Your Own 3AM and Make Cocktails Blue Again belie the mad skills of the staff.

To unearth how Hereford and his 15 or so cohorts do what they do, I followed him and his kitchen team, including chef de cuisine Colleen Quarls and sous chef Michael “Swade” Swadener, the week before Mardi Gras. The goal: Discover how they make what I think is one of the finest representations of Turkey and the Wolf’s shrewd kitchen cosmology: fried chicken pot pie with the herbiest ranch dressing known to humankind. So he and Quarls and Swade, with regular interjections from other kitchen staff, like sous chef Nathan Barfield, walk me through how to make their turnover-resembling take on a pot pie.

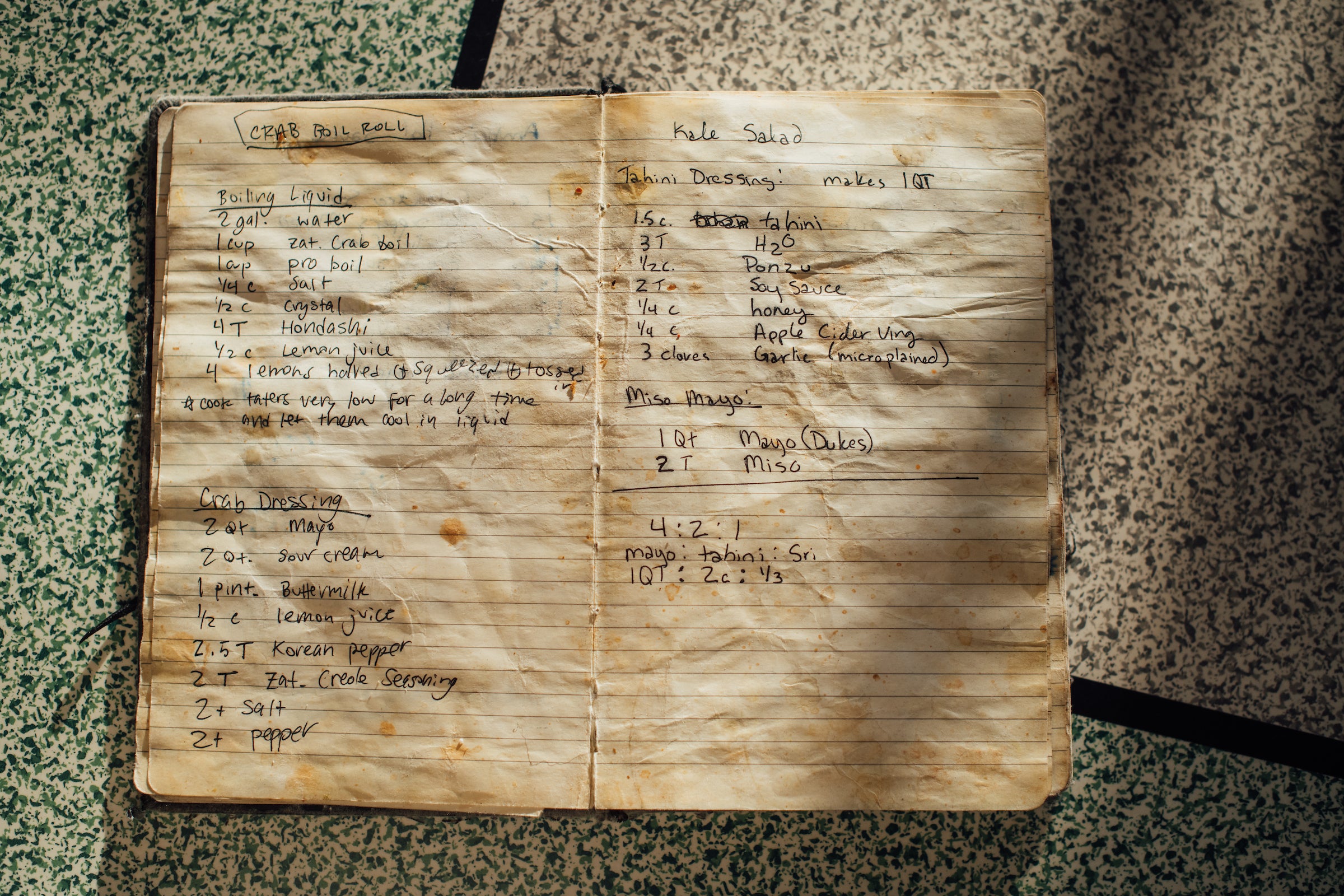

All the elements of good cooking are there. As Hereford puts it, “Herbs and texture are the keys to good food at the price point of a sandwich shop.” Then he nails one of Turkey and the Wolf’s essential mantras. “Plus, when I cook at home, I’m just trying to make the store shit taste good.” Store shit is Hereford-speak for premade ingredients: Kraft American cheese, frozen roti, and an endless stream of that Southern favorite, Duke’s mayonnaise. An element central to Turkey and the Wolf’s food ethos.

First, Hereford notes, you take a whole chicken—a good one, of course—and cut its backbone to help widen the bird’s surface area. You don’t remove the backbone, though, “because you want more things to make the dish taste like chicken.” He seasons the bird, heavily, with salt and pepper and browns it over medium heat in a skillet. Then he adds add chopped carrot, onion, garlic, and celery, plus bay leaves, rosemary, and thyme. Herbs: There’s going to be a lot of them, in every step of this pot pie’s creation sequence.

“The real fucking secret is that I use water and this,” Hereford says, waving a cylindrical can of Totole Granulated Chicken Flavor Soup Base Mix, chicken-flavored seasoning granules introduced to him by his friend, Nini Nguyen. “Chefs use it, but you know not everyone is into this because it’s made out of MSG and seaweed.” On review, this is not a product of the sea, in truth, but yeast and vegetable protein. People should be into Totole because it makes the finished pot pie taste like chicken squared.

As the chicken braises in the oven at 375 degrees, Hereford explains how dishes are born at Turkey and the Wolf. It’s a group effort. Always. One person comes up with a notion and the crew talks and fiddles and plays until everyone is happy with the result. “Part of why we’ve been able to find success with a dumb-ass sandwich shop is the team environment,” Hereford says. “I have no doubt this restaurant would be just as good—or better—if I disappeared, you know. It’s not my ship. It’s our ship.”

I would call bullshit based on my experience working or trailing in other restaurant kitchens. Not here. The staff loyalty; the easy, joking camaraderie. Hereford’s words ring true. Though there are exceptions to every rule: Within the first year of Turkey and the Wolf’s existence, Hereford and the restaurant’s other founding partner—and Hereford’s then girlfriend, Lauren Holton—parted ways.

Now it’s time to strain the chicken and reduce the cooking liquid. Once it’s reduced, Hereford presents a new trick: chicken roux, a blond mix of rendered chicken fat and flour. A theme recurs: More chicken-y elements means a more chicken-y pot pie.

In go more herbs, this time chopped fresh thyme and rosemary, and Hereford turns to Quarls. “How in a word should we describe the thickness of how we want the liquid?” Hereford asks. “Velvety,” Quarls replies. “Um, like coating the back of a spoon. The perfection description is like Velveeta. Like sticks-to-the-chip-in-queso-but-isn’t-too-soupy.” Barfield sees an opening, as Hereford pulls out a mixing bowl. “Is this the first time you’ve made this dish since the first time you made it?” Hereford chuckles. “Hey, shut the fuck up, bro.”

The braised chicken meat is stripped from the bones, and everything, including sautéed finely diced carrot, onion, and celery, is mixed together to make the filling. I blink; a barrage of seasoning begins. Salt, more chicken powder, and an array of chile-based spice: Crystal hot sauce, Sriracha, gochugaru (coarse-ground Korean pepper flakes). “Get in here, Swade,” Hereford says. They both taste. “I don’t know why it got sweet.” “Cuz you fucked it up,” Swadener notes. “Fucking asshole. More salt. It’s good otherwise. Spicy on the back end.” “Just a little more heat,” Swadener corrects with a jolt of burnt-orange Crystal. Behind us, the photographer, Denny Culbert, is shooting most of the staff. The noise level rises as both the front-of-house and kitchen start slamming shots of tequila and popping cans of Tecate.

Hereford reaches into the freezer and waves the dough for the pot pie. It’s another store-bought treasure: flaky roti paratha from Spring Home, a Singaporean brand of frozen bread that is the same base for the shop’s famed open-face lamb roti. On one side of a roti circle goes a lump of pot pie filling. Hereford folds over the empty side, forming a half-moon, and crimps it shut with a fork. He sets the crescent in the deep-fryer and weighs it down with a fryer basket to prevent bobbing. Nine minutes later, the pot pie is blistered and browned in the way redwood bark is. Like a McDonald’s apple pie, back when they were fried and actually delicious.

For the accompanying sauce, more herbs. Of course. This time loads of fresh tarragon are added to a thick buttermilk dressing spiked with Zatarain’s Creole Seasoning, a common packaged variation of that staple south Louisiana spice blend of red pepper, garlic, onion, and salt. Finally, the pot pie itself is dusted with a mixture of salt and more Totole. I yell, “Of course you finish it with more of that!” Because at Turkey and the Wolf, everyone knows that fresh-made isn’t always the same as better.