In 1983, publishing legends Angus Cameron and Judith Jones hunted and gathered a branded cookbook project lost to time. That is, until one writer spent three days in the woods with it as company.

A few years ago, I found myself in a pinch. I had borrowed a friend’s cabin that sat along the Housatonic River in the shadow of northwest Connecticut’s Bear Mountain, an equally short distance from the New York and Massachusetts borders. I brought my dog, my laptop, a pair of hiking boots, not one but two hunting knives, a bottle of Blanton’s Single Barrell Bourbon, a can of bear spray, and the hope that I wouldn’t have to use it. Since I was there to knuckle down and finish the book I’d been working on, I only brought two things to read: a novel, and a copy of The L.L. Bean Game and Fish Cookbook by publishing legends Angus Cameron and Judith Jones. My intention was to cook all three dinners I would eat at the cabin using recipes supplied by Cameron and Jones.

I failed. Miserably. It only made me want to try harder.

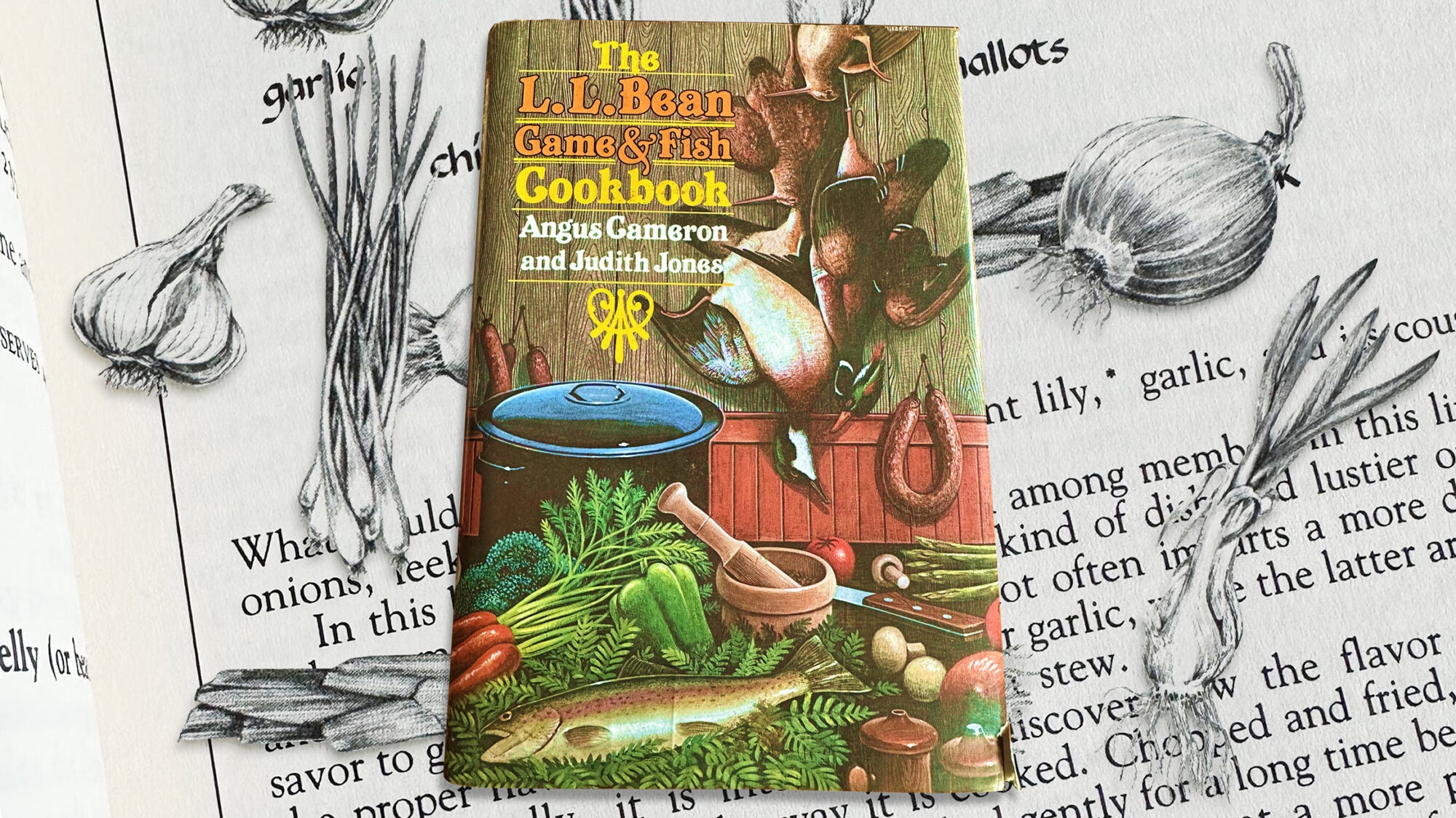

The book was a curiosity. It was published in 1983 as both a brand extension and a passion project, during an era of food defined by big concepts or articles that said something to the effect of “X is the new sushi,” where X was almost always some ethnic cuisine that became a watered-down and more expensive version of the real thing. I flipped through the pages and could imagine some urban yuppie caricature with his slicked-back hair and Armani suit in an eatery with minimal decor, being offered the sweet-and-sour muskrat or bear fillet in Burgundy and saying, “Rustic Maine is so in right now.”

Add in the fact that I’m a lifelong customer of Freeport, Maine–based L.L.Bean, and spending a few dollars at a used bookstore to get a book with old-timey font and an illustration of a couple of birds hanging upside down was a no-brainer, whether I ever used it or not. But there was something else. The names on the cover of the book, Cameron and Jones, meant it was a project by a pair of legends in the publishing world.

Along with editing the second edition of The Joy of Cooking in 1936, Angus Cameron had a hand in the careers of a number of literary luminaries, from J. D. Salinger to Lillian Hellman, before being forced from his position for his leftist beliefs during the McCarthy era. Jones, meanwhile, is celebrated as one of the most important editors in American history for her work on Mastering the Art of French Cooking by Simone Beck, Louisette Bertholle, and, of course, Julia Child. But she also famously plucked Anne Frank’s diary out of the rejection pile, worked with Edna Lewis on The Taste of Country Cooking, and was trusted with manuscripts by literary lions from Langston Hughes to John Updike and Albert Camus. I loved the idea of Cameron and Jones testing out game-centric recipes like braised caribou or roast possum with spiced apples and sweet potatoes.

With all that in mind, and an awareness that the pair were recognized for their work on the books of others and not their own, I felt comfortable believing this wasn’t some sort of ill-advised cash grab—a weird branded partnership with the Maine company known for its duck boots and canvas tote bags. Sure, L.L.Bean had been enjoying a new, larger audience outside the East Coast thanks to the smash success of The Official Preppy Handbook in 1980, which lauded the brand as the prep’s outdoor clothing provider of choice. Instead, Cameron and Jones, longtime colleagues, “had been talking for several years about a fish and game cookbook,” as noted in the introduction. The pair had been cooking fish and game for years as well: Cameron on 40 years’ worth of hunting and fishing trips that brought him to East Coast lakes and the forests of Alaska, while Jones had grown used to cooking game meat while living in France after World War II.

The book’s bona fides are hardly lacking. And while Cameron and Jones snuck in some of their own recipes for the project, they also worked with L.L.Bean, going through the archives of the company’s fish and game cooking classes that were offered at retail stores until 2018, usually by local partners who came in and taught customers how to cook what they caught. The duo rounded out the collection of tips and dishes by talking to L.L.Bean employees and Freeport area locals to find out how folks from Maine truly cook. The purpose of the book might be best summed up by a line in the introduction: “Even many experienced cooks are not sufficiently aware that good game dishes often depend on knowing as much as possible about the game in question.” The hope, they wrote, was that “we have produced a book that the late Leon L. Bean would have approved of; and it is equally our hope that this book reflects in some general way that mix of the traditional and the modern that characterizes L. L. Bean in the last quarter” of the 20th century.

As for the intended audience, the introduction noted an “increasing number of cooks who do not shoot but love the taste of game.” This was the era when establishments selling “specialty foods” like Dean & DeLuca or Zabar’s became more popular, and if late 1980s films like Baby Boom, Funny Farm, or Beetlejuice were any barometer of the culture, city folks loved the idea of country life. If one was able to make the move from Manhattan to rural Massachusetts or Connecticut in the 1980s, the L.L.Bean cookbook could be useful. As it’s mentioned at the start, a number of the recipes make for good campfire meals, and a few could be easily prepared under canvas—these are marked with a little tent.

The book’s recipes are almost entirely concentrated on critters and fish you’d find in New England. There are recipes for moose, deer, and wild boar—which are not indigenous to the area, although “feral swine” can be found roaming certain parts of the region, like northwest New Hampshire—using everything from venison tongue to moose à la mode (the recipe asks that you “do try to include the two split calves’ feet” in the hearty roast). There’s also a section focused on bear meat, which the writers argue is better than people say it is. If you tried bear and didn’t like it, the problem may have been that the bear itself was “ancient, skinny,” or it wasn’t butchered right, but it can be “a delicious red meat as fat as pork.”

The chapters take you through various game birds and fish (both freshwater and saltwater), small, furred creatures like beaver and muskrat, and soups, sausages, sauces, and burgers. The most beautiful thing is that nothing in the book is very complicated, especially for anybody who already spends a little time in the kitchen. The only catch is getting the meat or fish. Besides that, the recipes are quite accessible—especially the ones from Alex Delicata, the resident L.L.Bean chef who helped present the company’s annual game dinner so that locals and employees could try many of the recipes in the book. His recipe for roast venison chops, for instance, came in real handy when a hunter friend gifted me some deer meat. Delicata coats six to eight cuts of deer with a couple of eggs, milk, a garlic clove, dried basil, and two cups of crushed saltine crackers, and it comes out with a consistency I’d describe as schnitzel-like.

Overall, the recipes featured tend to be driven by the availability and quality of the meat, which might present a problem unless you’re handy with a rifle and know how to clean what you kill. For example, I’ve never come across “coot meat” before. The water birds are usually easy to spot swimming in open water, with their black plumage making them look like goth ducks. But since coot meat isn’t easy to find for those of us who aren’t a good shot, I suppose I could just go to a grocery store and buy a duck if I don’t feel like venturing out into the woods and shooting at something, but that defeats the purpose of the book. You’re supposed to be cooking an animal that was just on the land or in the sea—not an item pulled out of the Whole Foods refrigerator.

As a guy who lives in a city and does, in fact, do most of his shopping at a grocery store, talking up wild game might seem like an attempt to sound macho, or at least like taking this text a little too literally. I grew up fishing and can clean and gut what I catch, but truth be told, I don’t love doing it. And I will admit that my hunting skills are extremely limited at best. Still, I know enough about eating things that were recently caught or killed that I can confidently say the difference between something you buy at a grocery store and a butcher shop is large. There’s a reason they call some meat “gamy.” It’s because that’s what it is. It’s wild game. It’s leaner, and it often has very distinct natural smells and flavors that you aren’t going to get from cuts that are organically fed and farm-raised. And that’s what I intended to eat when I made my way up the highway and into New England.

My first night seemed like it would be by far the easiest. I had a lead on a guy who my friend said hunted game birds and would likely sell me something if he had any extra. I drove up the Taconic State Parkway with visions of using my L.L.Bean cookbook as my guide after the guy handed me a recently shot woodcock or pheasant he’d had hanging in his shed. According to Cameron and Jones, the temperature was just chilly enough for that sort of thing. They write, “But, and this but is very important, do not hang undrawn birds in warm weather.” The temperature should be in the 30s or 40s Fahrenheit at night, and no higher than 50ºF in the daytime.

Grouse sounded interesting to me, and the time of year was right for it. We were in the part of the calendar when the bird “varies its diet considerably” and isn’t relegated to the “needles and buds” it tends to live off in winter. I’ve had grouse before, but I haven’t prepared it myself. Yet I’d agree with the opening paragraph of the book’s section on the bird that “if pressed I would have to say that ruffed grouse is first among equals when taste is criterion.” The grilled version stuffed with oysters à la Rockefeller sounded fun, if perhaps a bit ambitious after a long drive. And I tried not to get my hopes up, since the book points out that “the bird is hard to come by,” because grouse is really good at hiding deep in the woods. I figured that if I was lucky, I wouldn’t get too crazy—maybe I’d do the Italian-style casserole and have enough for a few more meals over the coming days.

Yet when I showed up, my dreams were dashed. The man informed me that duck season had just started and he had only bagged a few the other day. He did have a frozen bird he could sell me, but that would take too long to thaw for dinner. He pointed me to a market where I could buy duck breasts supplied by local hunters. So I did that, deciding on the broiled duck recipe from the wild duck section of the cookbook. If I had my way, and an entire bird, I would have gone with the roasted duck with gin and juniper sauce, but the recipe I chose is described simply as “a very good way to prepare this toothsome bird.”

You’re supposed to be cooking an animal that was just on the land or in the sea—not an item pulled out of the Whole Foods refrigerator.

I picked up some supplies at the market, including some good-quality butter made nearby at a Connecticut farm. The book didn’t call for a particular kind of mushrooms, so I bought oyster. I also picked up some lemons and a bottle of port, of which I intended to use only a quarter cup and leave the rest for my host. The writer of the recipe blurb mentions that they like their duck “just barely done but not rare,” and I’m a big believer in the chef’s suggestions, so I went with that. I melted my butter, added lemon juice and pepper—the recipe called for white pepper, but I forgot to buy some—and then got to work basting my duck breasts. I sautéed the mushrooms the way the book directed. On the side, I made some simple roasted cabbage with salt, pepper, and red pepper flakes. My first meal from The L.L. Bean Game and Fish Cookbook wasn’t what I had envisioned, but I blame myself. I may have overcompensated with the seasoning. The final product wasn’t exactly handsome, either. It tasted good, but that was thanks to the bird. I find that planning these sorts of things hardly ever works out the way you intend.

The next morning, I went to a gas station and picked up some bait. I had my friend’s fishing pole with me, and I was pointed about 15 minutes south, though the guy giving me the directions to the spot mentioned that it was fly-fishing only. I told him that I’m not much of a fly guy—I don’t have the patience for it—and I was really just looking to catch a fish for dinner. He shook his head as if I had offended him, then scratched his forehead before telling me, “I suppose you could drive half an hour south,” directing me to a dirt road that I was supposed to take for half a mile. “But I’ve never had much luck down there,” he added.

I should have taken that as a warning, because the trout I had hoped to make over a campfire, à la Jones and Cameron, did not seem interested in what I had to offer. After two hours standing on the shore like a figure in a Romantic-era painting who is obviously overthinking everything, all I had to show for it was some lousy quiet contemplation and no fish for dinner. When I left and drove far away to regain cell service, I looked up a place to buy fish, and they mercifully sold me a beautiful trout that I sautéed with the head and tail still intact. I started with a glass of Sauvignon blanc and then moved on to the six-pack of Narragansett that I enjoyed before, during, and after the fish as the fire burned and I listened to a playlist my friend had titled “atmospheric black metal” through a little Bluetooth speaker. It wasn’t unlike other trout dishes I’d had in my life—very simple to make, with a little flour and a lot of butter, some minimal salt and pepper, and then a squeeze of lemon. The flesh was tender, and the outside was a nice golden brown. The book asks, “Can there be any tastier dish than the one that comes from this happy marriage of fresh trout and butter?” and the answer is, “Nope.”

The next morning, I woke up to my dog whining for breakfast and a pounding in my head. It was my last day for writing in the little home I was borrowing, and I realized that it would be a tough one. I was going to have to rally. The two hours I had carved out in hopes of trying to catch some fish again had to be scratched out. I suppose I could have tried, but I didn’t. I ended up grilling a couple of burgers later that night instead. As I ate, I leafed through The L.L. Bean Game and Fish Cookbook.

I could have made the “Buck and Bourbon” stew that’s “Good with moose or any other red meat,” if I knew how to hunt. I could have tried something I haven’t eaten, like oven-barbecued woodchuck, or a different take on a type of meat I’ve had, like a rabbit curry. I could have felt bad that I had become the living embodiment of the guy from the city who tries to half-ass a rustic lifestyle by cooking a few of the recipes Cameron and Jones lovingly supplied.

But ultimately, I realized that The L.L. Bean Game and Fish Cookbook isn’t really the sort of book you use to whip up something to eat that night, at least if you’re a little timid when it comes to preparing anything that was recently caught. I didn’t even have to bother with any of the cleaning, but if I had, it’s likely things would have turned out differently, and not in a good way. The sort of recipes Cameron and Jones present is food that you cook because you have patience, you have time, and you know how to catch food in the wilderness.

I have neither patience or time, and my rudimentary angler skills couldn’t snag me anything worth taking home. But even for me, the recipes translated into something delicious. They showed me that no matter what, cooking is simply that, regardless of what kind of meat or fish you’re using. If anything, Cameron and Jones provided a way to better understand what flavor profiles work with the critters and birds we may see on walks through the forest but never consider for dinner. And while you can usually depend on finding some duck, goose, or venison at your local grocery store, the bigger lesson of the L.L.Bean cookbook is that we should all at least try to learn how to get closer to what we eat.

But at least there’s duck in the grocery store.