At a certain point during his one of his first meals in Macau, the Chinese territory and glittering gambling mecca that sits on a peninsula 40 miles west of Hong Kong, Abraham Conlon was hit with a deep wave of melancholy.

“I was like, man, I’m gonna miss this,” says the chef and cookbook author.

The food—a unique fusion of Portuguese, Chinese, and Indian flavors Conlon enjoyed in a buffet-style, subterranean food hall—had triggered saudade, a Portuguese term that refers to the longing for something that’s currently taking place, an in-the-moment wave of sadness that stems from a knowledge that the experience is not going to last. It happens at live concerts (a rare Blur gig, or the Misfits playing with Glenn Danzig), or during the autumn of a relationship. And that day Conlon had suadade over a plate of squid rice. He had it bad.

“I saw all these things—sausage-based stews, curried crab—I had either eaten as a kid or become familiar with through my travels as a chef, and I experienced their flavors simultaneously,” says Conlon. “I started missing it before it was gone.”

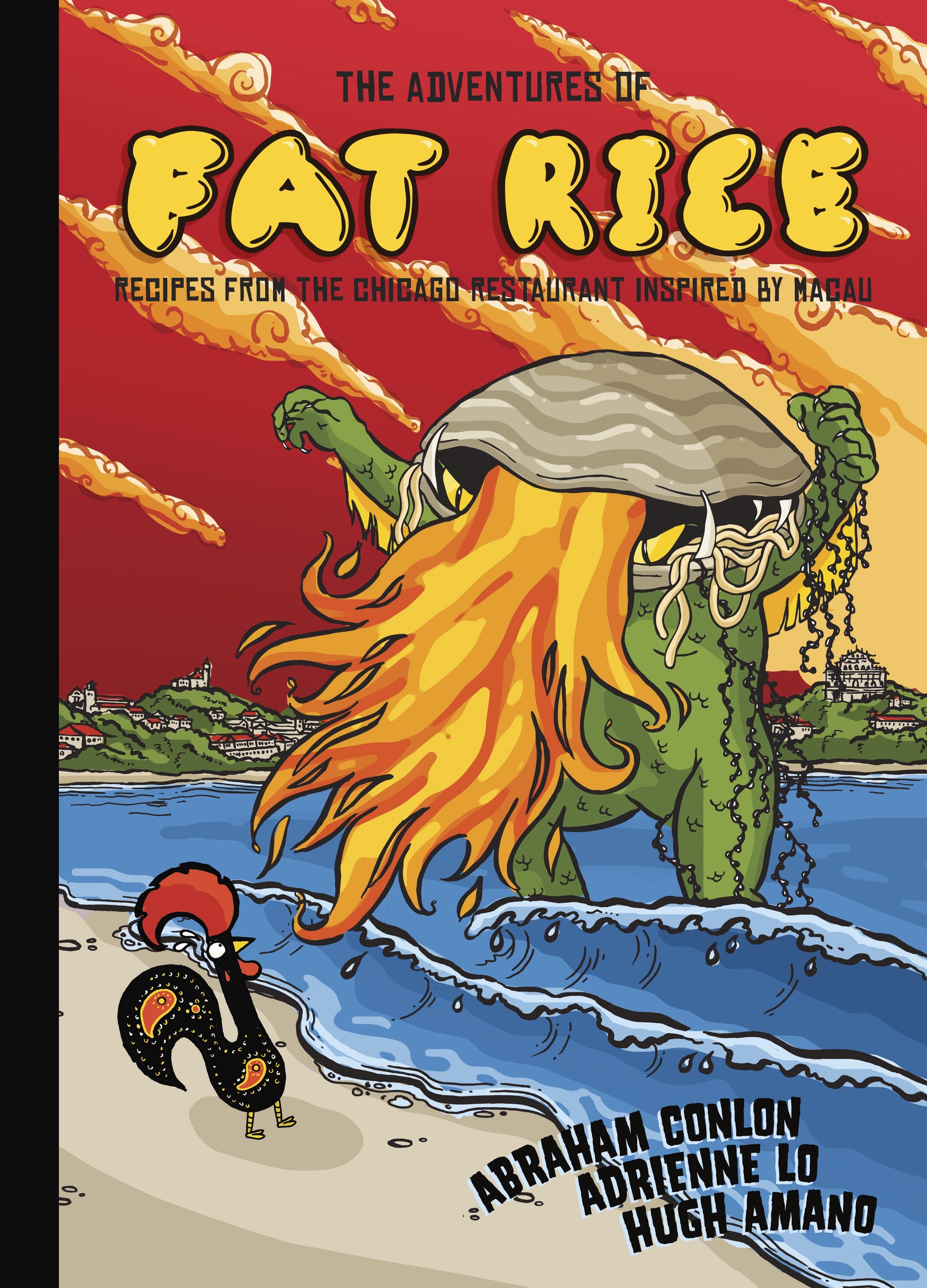

Except Conlon and his partner, Adrienne Lo, held onto the feeling. And a few years later, they opened Fat Rice, the award-winning Chicago restaurant that serves dishes inspired by Macanese cuisine—that is, the particular food of the peninsula’s endangered Portuguese-Chinese community that, while delicious and familiar to many fans of Asian cooking, has yet to have its bright, shiny moment in the mainstream. In their new cookbook, The Adventures of Fat Rice (Ten Speed Press), the pair, along with former Fat Rice sous chef Hugh Amano, share the story of their journey and celebrate the unique cultural mashup of the cooking. Eighty-six recipes as well as historical accounts, Pop Art illustrations, and a dao-sharp sense of humor populate the book, all of which serves as a way to document—and preserve—the dwindling culture and food of Macau.

Macau is a place best known for its shimmering casinos. Yet outside the flash, a complex food culture thrives.

Conlon and Lo met while working in a Chicago Whole Foods. Lo, a first-generation Chinese-American, was born and raised in the city; Conlon, who is of Irish-Portuguese descent, grew up in Lowell, Massachusetts, and after graduating from the Culinary Institute of America and spending time in several kitchens up and down the East Coast, landed in Chicago with the hope of scoring a job at Alinea.

Each had an innate love of food (Conlon learned to cook in high school; Lo in college) and a fierce case of wanderlust (Lo spent time in India and Italy; Conlon roamed various kitchens in Portugal and Asia). They started dating after Lo attended a Christmas cooking class taught by Conlon at Whole Foods; a few months later they launched X-Marx, a pop-up dining club hosted in their apartment that appealed to their untraditional nature.

X-Marx gained a cult following, and the duo continued to cook and travel, always striving to educate themselves in and experience world cuisines. In 2010 they traveled to China to study up on—and eat—the Sichuan cuisine they mutually adored. Conlon, who as a young man was intrigued by the food of Macau after reading a 2001 article in Saveur by Margaret Sheridan called “Original Fusion,” knew they had to make a last-minute trip.

“I remembered reading that there were certain people there trying to preserve their culture through their food, which was this amalgam of these different cultures,” says Conlon. “That really resonated with me.”

Macau is a place best known for its shimmering casinos and shifting identity. A prominent trade outpost, the province attracted the eye of spice-route sailors and, after some negotiations, became a Portuguese colony in 1557. China still maintained ownership of the peninsula until 1887, when it was signed over to Portugal, remaining under the country’s ownership until 1999.

When writing “Fat Rice,” the authors scoured the earth for traditional and unconventional cookbooks.

This influence imbued the area with a stark sense of duality that can be seen everywhere from the street to the slowly disappearing traditional dishes. Known as cozinha macaista, the home-style cooking sees Portuguese fare like bacalhau and linguiça mingling with aromatic stews and noodle dishes distinct to China and Southeast Asia; spices from Africa, India, and the Middle East are often included, too. “Fusion” is a bad word in cooking these days, but the food of Macau is hearty, rich in flavor, and wholly original; it is no slapdash Little White Chapel cuisine but a proper marriage of tastes that evolved over 400 years.

Armed with a Lonely Planet guidebook, the duo enjoyed a frantic few days in Macau, sampling the Portuguese-, Indian-, and Malaysian-influenced dishes at a variety of stalls and restaurants. They enjoyed the food, but it didn’t affect them until they ate at Riquexo Cafe, the saudade-triggering subterranean eatery.

“What we were eating could be found in different forms around the region, but it wasn’t food for tourists,” says Conlon. “It was meant for people who wanted sustenance and nostalgia and then move on.” Stirred by the meal, Conlon and Lo befriended the chef, 94-year-old Donna Aida de Jesus, an influential practitioner and preserver of traditional cuisine; she cooked for them and led them to eateries of note, where more revelations followed. (Later, Conlon realized Donna Aida was the very woman featured in Sheridan’s article.)

Upon returning home, the pair continued to host their X-Marx dinners and hone their skills, but after about a year they retired the popular event. “It was tiring, and there were too many cease-and-desist letters,” says Conlon. They’d always been interested in opening a permanent restaurant, however, and when it came time to define the theme, one cuisine kept popping up: Macanese.

“As we were getting into the food more and more, we started seeing the dishes that naturally brought together all the things that we were trying to bring together so unnaturally,” says Lo. “And we both wanted to preserve and celebrate this delicious, honest food.”

Wine service at Fat Rice in Chicago

Fat Rice is a direct reflection of this—and of them. The Logan Square restaurant sits in a cozy, open-air space made from reclaimed wood (inspired by an Antarctic hut) with bright murals splashed on the walls. The menu features spreadable salt cod and plump fried dumplings, hearty chicken stews and vegetable medleys featuring bok choy and mango, pork belly, chicken piri-piri and, of course, the namesake dish.

“We were trying to find a name that hinted at the cuisines of the places we loved,” says Conlon. “As we kept looking at the various foreign books we were using to study up, that phrase, ‘fat rice,’ kept jumping out.”

A clay pot packed with crisped jasmine rice, curried chicken, pork, duck, head-on prawns, clams, sausages, soft-boiled eggs, and tongue-blistering peppers, fat rice—or arroz gordo—is like the love child of paella and bibimbap. The dish originated on Macanese dinner tables, and its fusion of flavors and ingredients succinctly speaks to the spirit of the cuisine. And that name just so happened to have the perfect stick-in-your-head snap that would make any marketing professor do the Dougie upon hearing it.

“We didn’t want to be, like, I don’t know, ‘Saffron and Lotus,’” says Conlon with a laugh. “It just worked.”

The restaurant did, too. After Fat Rice opened in November of 2012, Mike Sula, a well-eaten reviewer for the Chicago Reader known for being particularly hard on restaurants specializing in Asian cuisine, gave it a glowing review. Armies of diners followed, as did numerous awards. And as more and more articles described it as, in Conlon’s words, “that Macanese restaurant,” he knew they had to do justice to the cuisine that inspired them. He and Lo took a scalpel to their menu, slicing off dishes they loved to cook but were more Indian or more Chinese, so as not to give the wrong impression of the food of which they were now heralders.

The Adventures of Fat Rice is a reflection of the restaurant’s first two years as well as the duo’s unique sensibilities. Will you make all the recipes in it? Not unless you make daily early-morning trips to the Asian stalls. But it is a beautifully written tale of two true originals who followed their instincts and stumbled into something they love. Conlon and Lo are part chefs, part cultural anthropologists, making several trips to Macau, befriending more chefs, and painstakingly combing through lesser-known Macanese meals and influences anywhere they can find them.

“We’ve done a lot of research when it comes to trying to find this cuisine, re-create it, and preserve it because, again, nobody knows about it,” says Lo. “Abraham’s always translating old cookbooks, calling up community centers and discussing their menus with them. We want to introduce everyone to the food—and the feeling.”

And that’s just it—a feeling. The food served at Fat Rice is all about the emotion behind it. Lo and Conlon are so intent on doing it justice because it synthesizes everything they care about—exploration, taste, and the cultures of China, Portugal, Southeast Asia, and India.

“Chefs are always in a way trying to come back home to their core influences,” says Conlon. “Cooking this food is our way of coming back home. And it just so happens it allows us to preserve something extraordinary, too.”

“Fat Rice” authors Hugh Amano, Abraham Conlon, and Adrienne Lo

Fat Rice’s Favorite Chicago Restaurants

Conlon and Lo’s love of “delicious, honest food” doesn’t end in their kitchen. Here are four of their most beloved ethnic Chicago eateries.

Nhahang Vietnam

Conlon: “I grew up eating Vietnamese food, and so whenever I’m in a new city, once I find my Vietnamese place, I’m good, I feel home. This restaurant has really, really great bahn xéo–the crispy crepe with bean sprouts and shrimp—as well as some really nice noodle soups and, of course, great báhn mì sandwiches.” 1032 W. Argyle St., Chicago, IL 60640

Bai Café|

Conlon: “This is a Kyrgyzstan restaurant. It’s a cab stand, so it’s open all the time. They do different types of stuffed breads, dumplings, charcoal kabobs. Fantastic.” 3406 N. Ashland Ave., Chicago, IL 60657

Café Orchid|

Lo: “This is a Turkish restaurant that’s just really delicious. It has this item called the Sultan’s Delight, which is a lamb dish with potato and cheese and eggplant that is really amazing. And they have really great red pepper salad, hummus and baba ganoush. They make their own bread, too.” 1746 W. Addison St., Chicago, IL 60613

Pakeeza BBQ & Grill

Lo: “This is another cabbie stand, and it’s an Indian-Pakistani restaurant. It sells a mixture of curries and lentils and meats and chickens and is just true homemade food.” 1011 N. Orleans St., Chicago, IL 60610