When the owner of San Francisco’s Burma Superstar needed fermented tea leaves to cook with, the search brought him to a factory in the remote mountains of Myanmar.

The steep, winding road to Namhsan, a town in northern Myanmar known for its superior tea, is literally being paved as we slowly climb one of the steep slopes in the Shan mountains. Our eight-passenger van has to stop every few minutes to queue behind a line of cars waiting for the tar to dry. Giant, dinosaur-like Komatsu bulldozers lumber out of the way for us to pass. Just a few months ago, there were no machines here. Even now, day laborers pour rocks from the side of the road in small patches while others follow with drums of asphalt, heated on the side of the road over small campfires. Myanmar (formerly Burma) is being pulled into its future so fast, its dwellers must literally avoid being crushed by the earthmovers reshaping their land.

This single-lane road is the only way to the heart of the best tea-producing region in Myanmar, the northern Shan state near the Chinese border—an area that’s been plagued by bloody civil war for more than half a century. I am traveling with Desmond Tan, the owner of Burma Superstar and five other Burmese restaurants in the Bay Area. We are here to buy tea—not to drink, but to eat.

Building the road to Namhsan

Until 2011, it was difficult to enter the country with a U.S. passport. It wasn’t until 2008 that, under pressure to rejoin the rest of the world, the oppressive and brutal military regime loosened its chokehold and a slow and painful transition to democracy began. My journey began in New York with typhoid and hepatitis A vaccines. We took flights on local airlines that provided hand-written boarding passes, paid road tolls to drug lords, replaced brake pads at twilight, and had a near miss with a nightmarish overnight traffic jam, all for one thing: laphet, or fermented tea leaves.

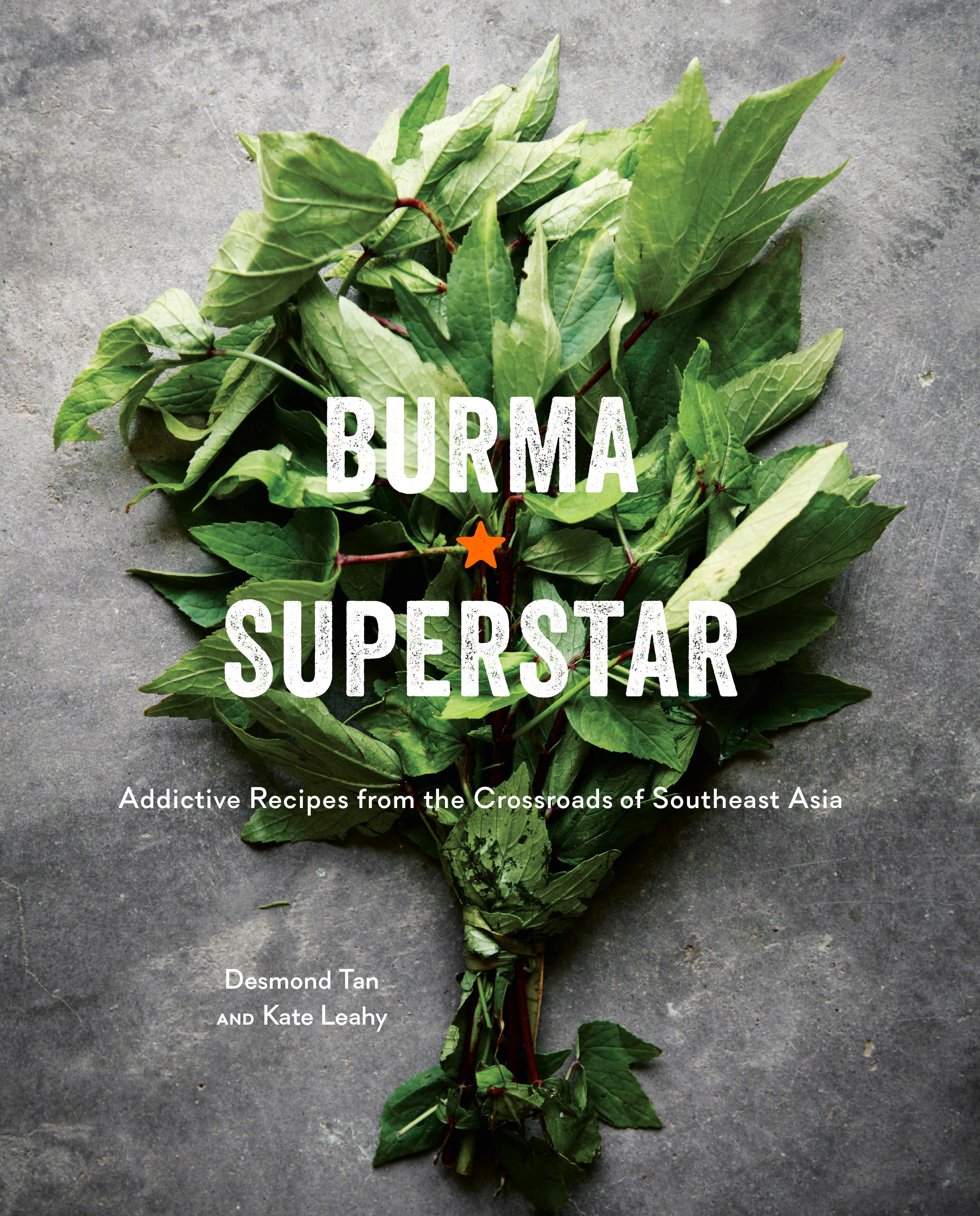

Burma Superstar

Laphet is the stuff of legend in Myanmar and nearly impossible to find outside the country. That is, until now, in large part thanks to Tan. For almost 50 years, this was a pariah state. Even the name is contentious. For most of the 20th century, this was Burma, so christened by the British, the colonial rulers from the mid-19th century to 1948, but in 1989 the governing body changed the country’s name from Burma to Myanmar and the capital of Rangon to Yangon. Tan’s family left the country in 1977 and eventually settled in San Francisco.

For more than two decades, Tan’s growing mini empire has been responsible for educating eaters—including myself—about the cuisine and culture of Myanmar. If you’ve had Burmese food, you’ve probably recognized the influences of India (spicy curries), China (noodles), and Thailand (fishy salads dressed in lime). Burma is bordered by Bangladesh, China, India, Laos, and Thailand. At Tan’s restaurants, Burmese tea leaf salad has always been on the menu. His Westernized version uses the fermented tea leaves like a dressing to coat a pile of crunchy romaine lettuce, chopped tomato, peanuts, toasted lentils, sunflower seeds, fried garlic chips, and a large squeeze of lemon. In Myanmar, the fermented tea is eaten by taking a small spoonful onto one’s own plate and seasoning it with fried peanuts, garlic, and chile.

Desmond Tan, owner of Burma Superstar and Burma Love

My own obsession with Burmese cuisine began, thanks to Tan, in 2007 at the Clement Street location of Burma Superstar, where I had my first sour, bitter, toothsome, and salty bite of laphet. It’s a symbol of hospitality in many Burmese homes. Laphet is served at roadside stands, presented as an offering in Buddhist temples, and used to welcome weary travelers and even to seal peace treaties. It’s one of Burma Superstar’s most popular dishes (more than 250 are sold each day at Burma Love, the group’s newest restaurant). There really isn’t anything else in the world like its delightfully pungent taste, closest perhaps in texture to a grape leaf but nothing like it in flavor. That unique flavor isn’t exactly easy to achieve.

The healthiest tea leaves reserved for making laphet are grown in sparse patches on steep mountain slopes, rather than organized rows in plantations, and must be harvested by hand in the spring to preserve the bushes for a second and third picking. Tan says the tea from the township of Namhsan is considered the best because of its terroir, which is excellent for cultivating and fermenting highest-quality tea leaves. After the leaves are harvested, they must be quickly steamed—to preserve color and flavor. Raw, the leaves are tough and bitter; the steaming softens the texture and leaches out some of the bitterness. Then the steamed leaves are buried in burlap sacks about 10 feet underground in giant cement vessels and pressed down with weights.

One of the first tea buds of the harvest

Tea sorting at Shan Shwe Taung

As the leaves ferment naturally, they take on a sweet, almost citrus-like flavor. This traditional practice is becoming scarce as large-scale operations increasingly rehydrate cheap tea from China. “We believe that the high-quality traditional laphet-making industry is in danger because local companies rely more and more on inferior-quality tea leaves and cheaper, artificial coloring (sometimes the same coloring used to dye clothes), artificial flavorings and additives to meet cost/commercial pressures competing for greater market share,” says Tan.

Tea Trouble

Tan, like the handful of Burmese restaurant owners in major U.S. cities, says he worked with individuals who would bring the fermented tea-leaf packets and sell direct to small Burmese/Chinese grocery stores. He eventually formed direct relationships with the individual importers, who would hide the packets purchased from grocery stores in Yangon in their luggage and bring it over using a tourist visa to and from Myanmar. This importation scheme went on for years, but Tan was tired of paying high prices for poor-quality laphet. “We discovered that nearly 10 percent of the ingredients were comprised of MSG or other preservatives and artificial colors. We wanted to have natural ingredients and better fermented tea leaf products,” he says. That’s when he started asking around Yangon to see if anyone could reveal a source for where laphet was made.

Looking for a Source

Tan has been back to the country of his birth many times since he emigrated at the age of 11 with his parents. With each visit comes the shock of this country trying to catch up with the rest of the 21st century. A new democratically elected government led by Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi is making attempts to stabilize the country and build basic infrastructure like roads and hospitals.

“This is incredible. None of this was here just a few years ago,” he tells me over a steaming bowl of mohinga, a pungent fish noodle curry, purchased from an airport shop before an early-morning flight from Yangon to Bagan. The brand-new Yangon airport is stunning and wouldn’t be out of place in a modern European city. The international terminal has luxury shopping galore, and Tan is shocked to see that a Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf will soon open.

Family eating at a roadside stop near the road to Namhsan

Laphet thoke in Namhsan

It was around 2011 that Tan started sniffing around the tea houses of Yangon and Mandalay looking for a direct laphet source. When he looked in the back of restaurant kitchens he found the same poor-quality packaged leaves he was used to importing. He asked restaurant proprietors and chefs where their tea leaves came from, and they’d lead him to wholesalers and distributors in Mandalay. He consistently hit dead ends as one wholesaler lead him to another who would give some vague answer about purchasing the tea from the Shan state, an area plagued by civil war since the British left Burma and often sealed off by the Burmese military. He recalls that even the local Burmese citizens did not know exactly where, or even how, their fermented tea leaves were produced. “They were purchasing prepackaged products loaded with MSG and food dye and using it in homes and restaurants,” he says.

Until recently, Burmese people would have been skeptical of a foreigner asking questions about the Shan state. Queries weren’t welcome in the paranoid, 1984-like state of Myanmar (one of George Orwell’s first novels was about his service in Burma under the British Empire), and Tan was frustrated but not surprised that no one wanted to do business with or even reveal sources to a foreigner. He could easily have been an informant.

Then, in Yangon, he met Bryan Leung. Leung is the type of guy who knows how to survive and even thrive in a place like Myanmar, making do with what he can and taking advantage of opportunities. Leung was also the link Tan needed to connect with a tea broker named Nelson Rweel. Rweel is originally from the tea-growing township of Namhsan and organized the co-op of farmers that now forms the foundation of Burma Superstar’s entire tea leaf enterprise. “The best laphet within Namhsan comes from Zayan, a village in the northern part of the township,” Tan writes in the new Burma Superstar cookbook.

A motorist in Namhsan

The Road to Mandalay

“Tea leaves” is a bit of a misnomer as the actual product comes from the buds, which begin to sprout in early April. The tea plants look like sparse bushes, haphazardly placed in winding rows that follow the natural slopes of the rocky hills they grow from. Unlike grape vines, which look tortured and craggy, tea bushes become lush with large green leaves for most of the spring and summer. When we visited in early March, there was a single bright green bud on one of the plants in a small patch of tea growing out back behind one of the larger fermenting houses. The particular variety grown in Namhsan is Assam (its botanical name is Camellia sinensis), which may be familiar to you as an Indian tea. But Burmese Assam is more robust. The first buds picked in early spring are best because the flavor hasn’t been diluted by rain. A second harvest takes place in June and often a third in late August. The buds are carefully picked by hand and steamed while they’re still green, then squashed into burlap sacks and buried in a cement pit inside a warehouse for at least three months and up to one year.

After the tea spends a few months fermenting, it is trucked down the precarious mountain road to Mandalay to Shan Shwe Taung’s factory. There, it is seasoned in large steel containers by workers with various combinations of oil, garlic, and chile, ground, and processed into different products: small, snack-size packets for breakfast consumption, jars for home cooks, large quantities for restaurants, and in Tan’s case, shipping containers filled with raw product.

Shan Shwe Taung factory

Fermented tea in burlap sacks

“The most challenging part of our effort was to figure out how to bring the thousands of pounds of fermented tea leaf to San Francisco,” Tan says. “Our first attempt was a huge risk as no one had ever shipped fermented tea leaf out of Myanmar to the U.S. There was a strong possibility that our container of over $70k worth of fermented tea leaf could sit on the docks or would not be cleared through customs. Most imports from Burma came through other countries, such as Thailand, India, Malaysia, Singapore or China—from that point ‘country of origin’ disappears—and not directly from Burma, as we had done. We successfully and proudly imported product ‘Made in Myanmar’!”

Once he had sourced a steady stream of raw product, Tan was able to spread laphet beyond his restaurant and package the seasoned tea leaves for wider consumption under the Burma Love label, which is now available in stores like Rainbow Grocery and Whole Foods in the Bay Area and at online retailers like Good Eggs. The arrival of the first container was a huge triumph, but Tan was still not fully satisfied with the quality.

Namhsan

This one-lane mountain town is lined with small shops and makeshift wooden homes. We’re in an open-air room that resembles a pop-up Baptist church in a strip mall for a meeting with Tan and his farmers, and the atmosphere is tense. Tan has traveled to Namhsan this time to go over quality-control standards—he’s hoping to remind the farmers that he’s paying a high price for premium organic product—but it seems the farmers are more concerned with prices and the promise of future business. Rows of pink plastic chairs are set up for the 30 or so farmers who make up the co-op of farmers Nelson has established. Tan has helped with funds to ensure the farms meet HACCP food-safety standards so the tea can be exported to the United States. The meeting is conducted in three languages: The farmers, all ethnically Palaung, speak to the tea broker, Nelson Rweel, in their native tongue; Rweel speaks Burmese to Tan, who then translates into English.

The farmers are dressed in khaki pants and bomber jackets and look like a ragtag bunch of fighter pilots sitting for a mission briefing. Their lives are not easy. A fire destroyed a lot of the picturesque wooden town in 2016, and there is much to rebuild. Here in this remote part of the Shan state, electricity arrived just a few years ago, and there is constant fighting between Shan rebels and the Burmese military (Myanmar Armed Forces, officially known as the Tatmadaw). It is a convoluted conflict that has been going on since the British left in 1948, centered around the fight for an independent Shan state. Just a few weeks ago, there was a skirmish in which a few soldiers were killed. The army retaliated by shelling a village of farmers nearby. One was at the meeting in March, his arm badly hurt in the attack.

But it’s not just warfare that makes life difficult for the tea farmers. With little to no government help, life in these remote villages is very different than it is in Yangon or Mandalay. Less and less tea is grown in this region because opium, grown just over the Chinese border, is a more profitable crop. Tea farmers are leaving their families and tea plantations to work the opium fields in China for a higher wage. A Myanmar Times article from 2013 claims there’s a labor shortage in Namhsan because Palaung women are sneaking across the border to China to marry wealthier farmers. In actuality, Tan is willing to pay whatever it takes to keep these farmers happy and alive; he’s here to ensure his dollars actually make it into the hands of the Palaung people. A handshake agreement on price is made, and both sides appear content.

Traditional laphet in lacquerware

A traditional Palaung lunch is then served. The crown jewel dish, of course, is tea leaf salad. It arrives in a lacquerware vessel with dried baby shrimp and cabbage. The traditional version of laphet, served in an ornate divided lacquerware vessel, consists of seasoned fermented tea leaves, a peanut and fried lentil mixture, and any number of other mix-ins, like whole chiles and garlic. With the first funk-filled bite, I am reminded why I have traveled over 9,000 miles to get here.

As it grows dark, our Burmese hosts get nervous. We have the right business visas, but the Burmese army would prefer that we weren’t here. Though Myanmar is slowly waking up from its authoritarian slumber, there is still a very long way to go. We are instructed not to leave the van until we clear the town. And even leaving Namhsan, there’s evidence of an increased military presence: A small battalion of soldiers has set up a checkpoint, and though we can see steel barricades, the road remains clear. It’s a tense 15 minutes. At last, relieved, we finally pass out of the town and into the beautiful countryside, dotted with tea plantations and sparkling golden pagodas just as the sunset casts a warm, pink glow over the misty vineyard-like hills.