Originally written as a pamphlet for young immigrant women, The Settlement Cookbook’s many editions have defined and documented the story of Jewish cooking in America.

As a child, whenever I was antsy and hungry for chocolate chip cookies or chicken soup, I’d retrieve my great-grandmother’s worn-out copy of The Settlement Cookbook. Where other homes had Betty Crocker or The Joy of Cooking to refer to for fundamentals, we had this yellowed, spattered paperback full of recipes for chopped liver, brisket, and grebenes. Though the recipes were solidly makeable, it was the tips on table setting and cleaning that held my attention. They felt like a direct line to my great-grandmother, whose fancy china and mink stole were wrapped up, unused, in different corners of the house. It turns out I’m not the only child of the Jewish diaspora with memories etched between the lines of this book.

Originally published in 1901, The Settlement Cookbook became a beacon of sorts to Jewish home cooks and their less culinarily inclined offspring. Authored by a social service worker in Milwaukee named Lizzie Black Kander, The Settlement Cookbook has become a benchmark of Jewish cooking in America, and remained relevant over a century after its publication.

Kander was a well-off descendant of German-Jewish immigrants who volunteered at the Settlement House, a charitable organization that provided health care, child care, and education to immigrant and impoverished young women. Tasked with teaching a recent wave of Jewish immigrants—many from Russia—how to, essentially, keep good, clean, middle-class homes, she thought a book might be a good way to do it.

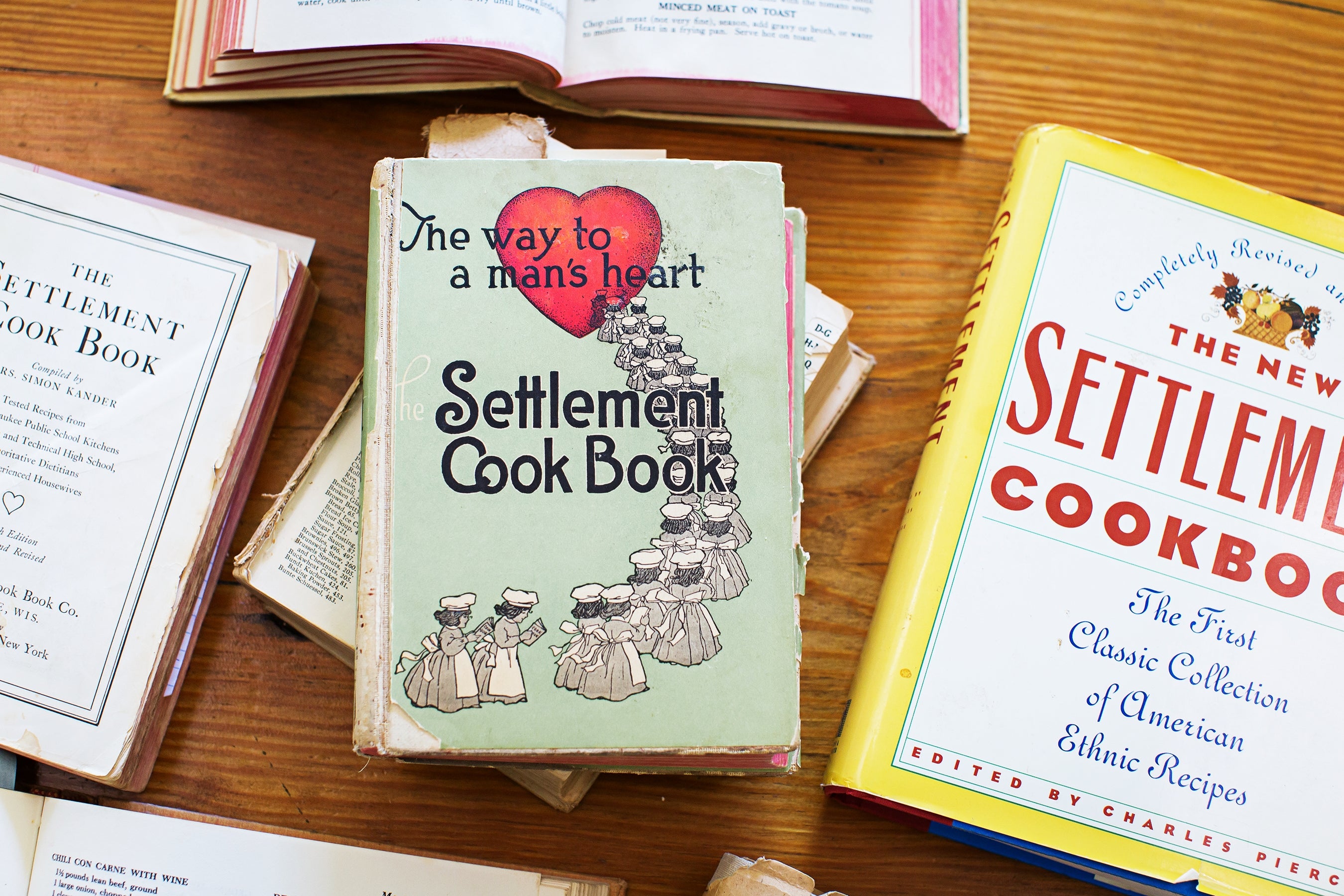

Kander couldn’t persuade the board of the settlement house she worked with to front her $18 to print a first edition, so she went out on her own to raise money and had 1,000 copies printed. The book’s tagline was “The way to a man’s heart,” and along with cooking instruction contained tips for cleaning spills and setting a nice table. It included close to 500 recipes collected from various European cultures, with suggestions for arranging them into menus.

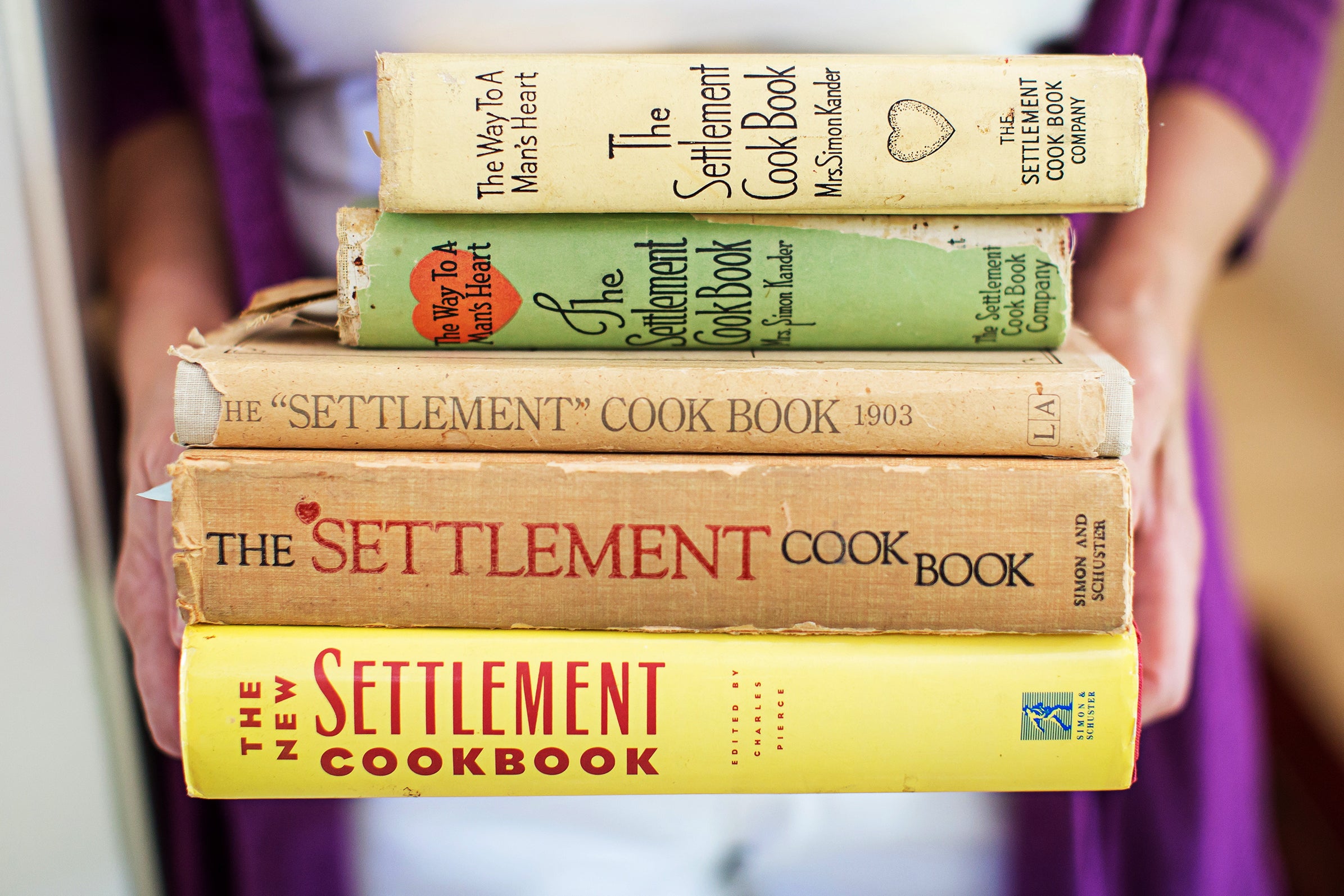

Cookbook author Joan Nathan with her collection of Settlement Cookbooks

That first printing was intended for the women at the Settlement House, as a study guide and reading primer. The language was clear and direct, the tone that of a stern but loving aunt, the underlying message that if you can master the domestic arts, you’ll have a happy husband, and if you have a happy husband, he’ll provide for you. Before there was Martha Stewart, Ina Garten, or Gwyneth Paltrow, there was The Settlement Cookbook telling women that if they used a tablecloth—even a cheap one—they could have better lives.

This, it turns out, was something women were looking for. The first edition sold out within a year, and Kander had little trouble raising funds for a second edition.

Since then, there have been more than 40 editions printed and more than 2 million copies sold. During Kander’s lifetime, proceeds went to the Settlement House, making this book the highest-selling fund-raising cookbook ever. In addition to my great-grandmother’s copy, which lives on my nightstand and is so delicate that I hate to open it, I have a 1991 edition, The New Settlement Cookbook. But my collection is amateur stuff.

Cookbook author, journalist, and archivist of Jewish cooking Joan Nathan has somewhere around 20 Settlement cookbooks—“Eighteen is always the number that gets quoted,” she says—including two facsimiles of the original edition. Why such dedication to a single text? Simple. “It was the cookbook my mother always used,” recalls Nathan.

“My mom had a well-worn copy of The Settlement Cookbook on her cookbook shelf—the one with the line of toque and apron-clad women clutching cookbooks and winding their way towards a heart,” Leah Koenig, a food writer and the author of Modern Jewish Cooking, tells me. “I don’t remember my mom ever cooking from it, but I know it was very dear to her. It originally belonged to my grandmother, who got it as a wedding shower gift in the 1940s and used it extensively.”

A cover from an early edition of The Settlement Cookbook depicts aproned women finding “the way to a man’s heart”

In a time when most women never lived on their own before marriage, this book was sort of a crash course in how to run a house. Kander personally revised each edition up until her death in 1940, and she updated ingredients and recipes to reflect the times, so the book felt modern.

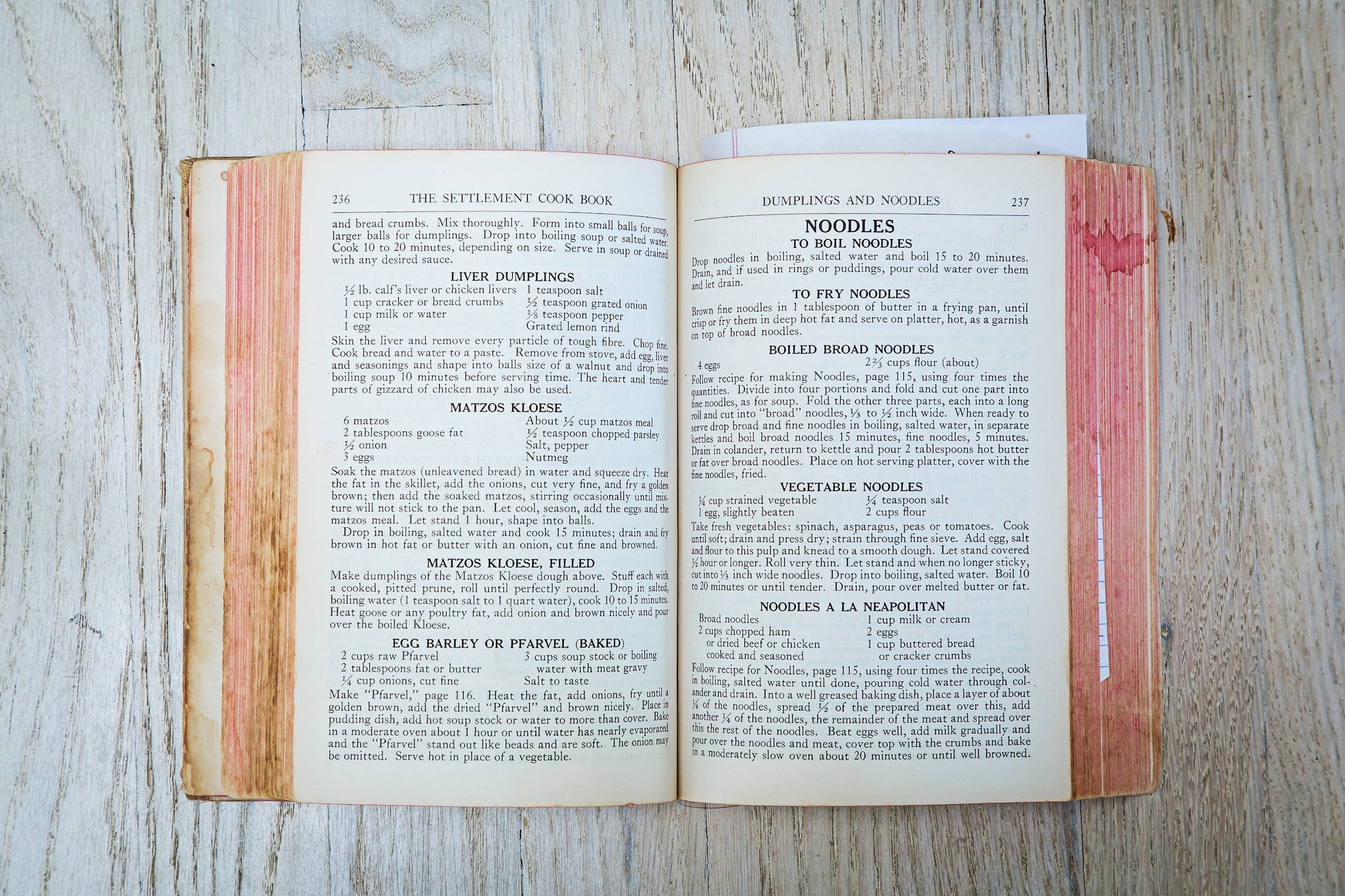

At settlement houses like the one Kander was working in, marriage and a happy family home were the endgame. The goal was not to preserve old-country culture, though it did help preserve the peasant cuisine made by bubbies. (A lot of the people who cooked these traditional dishes, like my own two great-grandmothers, were illiterate. Were it not for The Settlement Cookbook, there might not be a record of these recipes.) The goal was, to some degree, to strip away those elements of the old country, soften them around the edges, and make them palatable to people outside the immigrant community—to keep husbands and culturally American children happy, healthy, and well-fed. While there are recipes we’d recognize as Jewish today, including recipes for kishke, kreplach, both meat and dairy borscht, farfel, and cabbage pudding made with goose fat, there are also recipes that use pork and shellfish—not kosher ingredients. But Nathan says that is actually part of the appeal of the book.

“It’s American,” she says. “People like my mother’s family were not interested in [the old] recipes at all. They wanted to get away from that.” So on the one hand, this book was a way to do that.

Robbie Medwed, a Jewish educator in Atlanta, puts it concisely: “Jews who settled in the Midwest at the turn of the century were desperate to both assimilate and hold on to their culture. The Settlement House and its cookbook gave them the ability to do so while remaining connected to their culture and language.”

And that’s part of its enduring appeal, too.

“Contemporary American Jews mainly cook the same kind of foods that Americans [of different ethnic groups] cook most of the time,” cookbook author and food historian Jayne Cohen says. “They mainly make Jewish dishes for Jewish holidays. And the Settlement books offer mainstream and Jewish recipes reflecting that.”

But what’s especially interesting and important about this book is how much it’s changed in its 40 editions and four revisions. The Settlement House (later renamed the Milwaukee Jewish Center and then the Jewish Community Center) continued publishing it until the 1970s, changing recipes and tips, reorganizing the book, and addressing health concerns of the times. In this way, it’s also a sort of chronicle of Jewish-American culture, and how it has changed with the times.

The recipes in the book range from Eastern European classics to standards of American households.

In 1991, Simon & Schuster began publishing The New Settlement Cookbook (axing the dated “way to a man’s heart” subtitle). The balance shifted more toward recipes, doubling the number of them. In my 1991 edition, there are sidebars about low-cholesterol substitutes for dairy products and how to microwave a roast, as well as recipes for pad Thai and Southern-leaning corn cakes. It’s this newer edition that I looked to when I thought about revisiting kasha varnishkas, the food I loathed most as a kid. As in the older versions, the language is clear, the tone a little stern, the overall effect incredibly comforting.

These days I am drawn mostly to newer recipes and cookbooks—a dish from a restaurant I loved on a trip last year, or a volume authored by a chef I think is funny on Twitter. Or I develop my own. (That’s what I do for a living, after all.) The Settlement cookbooks hold a different space. I keep my great-grandmother’s next to my bed, because it’s too torn up and delicate for the cookbook shelf. I’ll crack open the 1991 edition for inspiration when I want to do something Jewish; I’ll study a classic recipe, then put my own spin on it. Both remind me of where my love of cooking began, and who I am.