From the Montgomery Bus Boycott to Bakers Against Racism, the bake sale has long thrived on grassroots activism.

As protests against police brutality broke out in cities across the United States in late May, flour swiftly exited the conversation. The quarantine bread-baking pastime was waylaid as millions took to the streets to fight for Black lives, and before long, the mundane lockdown activity began to, necessarily, feel like a distant memory. Asma Nizami, on Twitter, put it best. “I personally think it’s really cool how we all went from learning how to make banana bread to learning how to abolish the police in a matter of weeks.”

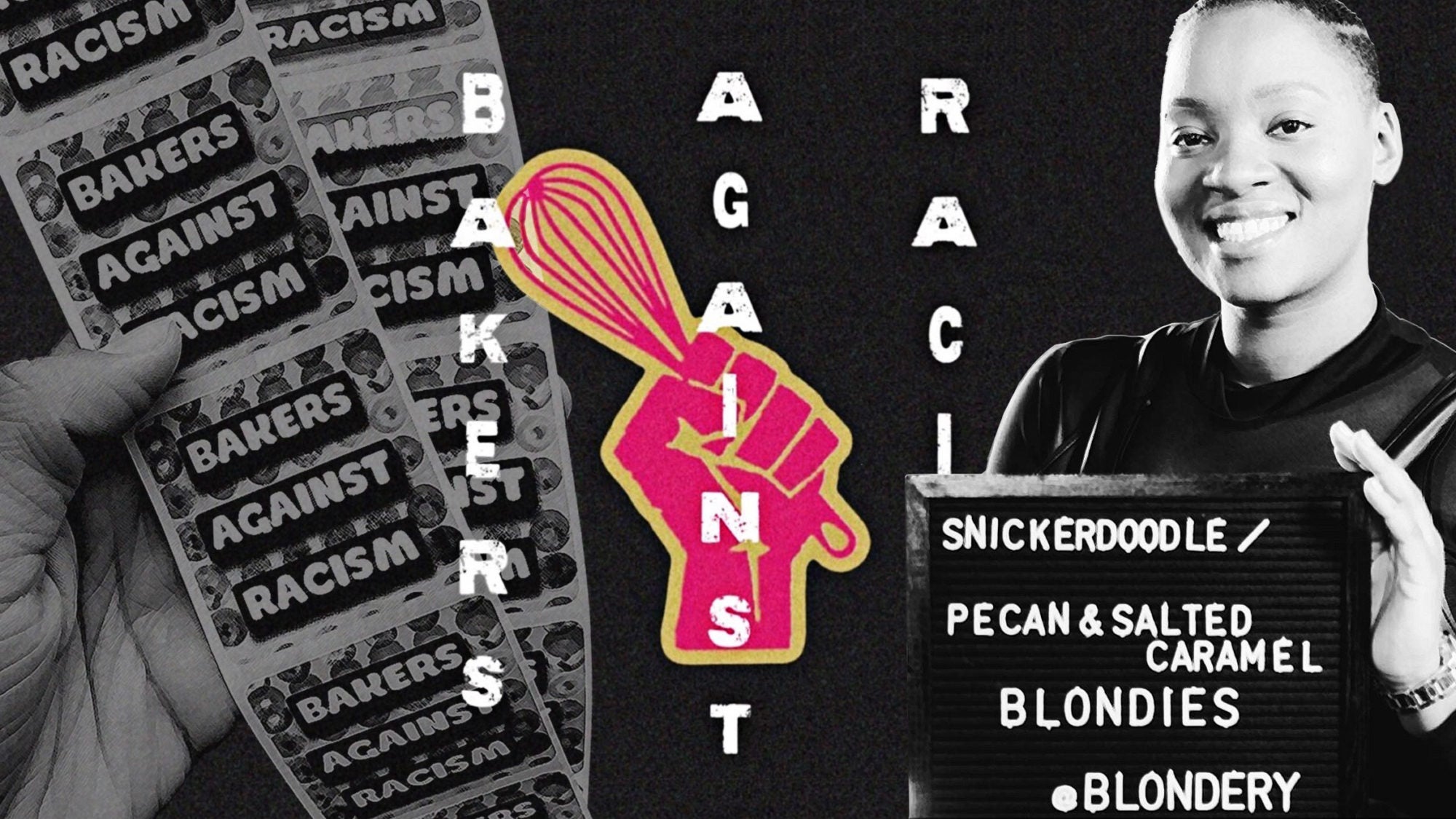

For Auzerais Bellamy, the pastry chef and founder of Blondery, a mail-order blondie bakery based out of Bushwick, Brooklyn, the flour never stopped flowing. “I’ve been baking since I was nine years old—pastry is something I can do pretty effortlessly at this point,” Bellamy says. As a Black woman in the food business, she has long been subject to racism in the industry as well as in the world at large, she says, so when she heard news of the June 20 international bake sale billed as Bakers Against Racism, she was instantly on board. Bellamy began organizing orders for her Blackout Brownies, a gluten-free brownie made with chocolate ganache, and decided to set aside 50 percent of proceeds to go to the Equal Justice Initiative. “We’ve sold around 100 boxes, and we’ve just restocked another 20,” Bellamy says. “We’re going to keep going until we sell out again.”

A decentralized bake sale that anyone, anywhere, can take part in, Bakers Against Racism is the brainchild of pastry chefs Paola Velez, Willa Pelini, and chef Rob Rubba. Velez, a James Beard Awards finalist chef at Washington, D.C.’s Kith and Kin, and Pelini, the pastry chef at D.C.’s Emilie’s, saw how organizations supporting the Black Lives Matter movement needed constant funding to post bail for protesters, send money to the families of men and women murdered by police, and continue the work of abolition and anti-racism long after the streets began to empty, so they dreamed up one way to put their pastry skills to good use for the cause. “If you have a special skill or special talent, that can also be used as a force of change,” Pelini told the Washingtonian in early June. “Everybody has a role to play, and you can use what you’re good at to push forward the cause.”

“I think that everyone who believes in racial equality needs to participate in this movement. Bakers and pastry chefs should use their desserts. Artists should use their artwork. Musicians should use their music.”

Thousands of food professionals and newly self-trained amateurs were practically primed for this initiative, as many pros had been laid off from their jobs in the wake of the coronavirus epidemic, and many at-home bakers had been busy honing their baking talents in lockdown. In less than a week, the sale had 2,400 sign-ups from 42 states in more than 170 cities in the United States, and in at least 15 countries. “I have been racially profiled and followed by police into my own restaurant because I ‘looked suspicious’ running inside to ask my coworkers to help unload a trunk full of pastry ingredients,” Jonni Scott, head pastry chef at Cranes in D.C., says. “I think that everyone who believes in racial equality needs to participate in this movement. Bakers and pastry chefs should use their desserts. Artists should use their artwork. Musicians should use their music.”

Each baker taking part was encouraged to decide which organization they would like to donate to. “Mass incarceration is another form of slavery, and that needs to change now,” Bellamy tells me, which is why—so moved by the work the Equal Justice Initiative had put into the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration in Alabama—she decided to allocate her bake sale funds to EJI. Bakers across the globe will send contributions to dozens of other organizations supporting the Black Lives Matter movement, like Loveland Foundation, the Okra Project, and Showing Up for Racial Justice. ThaVeganBaker, a vegan baker based in Berlin who chose not to share her full name, will be donating to EJI and Kop Berlin, a nonprofit fighting police brutality in Germany. “We’re still living under a pandemic crisis,” she says. “Not everybody feels safe to go out there to protest, but we can still make a difference through baking. As a Black woman, this is a way to support one of my communities.”

Bake sales have always been powerful radical tools for those deprived of, or lacking in, more formal political sway, which is why women were the first to host them. Daniel Gifford, who wrote about the history of philanthropy for the Smithsonian Institution and now teaches at the University of Louisville, estimates that bake sales have existed in some form for the entirety of American history. “Women have been contributing to the success of churches, organizations, and institutions throughout time without their work being explicitly acknowledged or celebrated,” Gifford says.

Bake sales were born from societal limits about what is, and what isn’t, a woman’s place or role, Gifford says, because men were expected to occupy the public sphere, while women were kept in the private one. Women upended those expectations by turning bake sales into powerful grassroots tools. It’s not surprising that women of color, continually banned from accessing formal political power, would have turned to this kind of activism as a means to fight racism. In the civil rights era, when many Black women in the South worked as domestic laborers and cooks, the bake sale was prime territory for political resistance.

“I think it’s important that—even after the bake sale ends—we continue to support. Black businesses are underfunded. We need people to support us.”

One of the most well known of these bakers was Georgia Gilmore, a Black cook from Alabama who used her domestic skills to raise money during the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Gilmore’s Club From Nowhere was an initiative in Montgomery that she started after she’d been fired from her job for playing a vocal role in the civil rights movement, testifying on behalf of Martin Luther King Jr. at his Montgomery County indictment.

She recruited women to sell plates of pork chops and rice, sweet potato pies, and pound cakes from their homes and at protest meetings, using the cash to pay for gas and cars to transport Black workers to their jobs while the boycott continued for nearly 13 months. In a 1993 journal article for Gender and Society, sociologist Bernice McNair Barnett conducted interviews with women who had been associated with Gilmore’s Club From Nowhere during the boycott. One respondent told her that it was common protocol to pay in cash to avoid the donations being traced. This way, Black supporters wouldn’t get in trouble with their employers and potentially lose their jobs, while white donors held on to their political and social standing.

Initiatives like Bakers Against Racism and the Bake Sale Project, a new organization founded by pastry chef Natasha Pickowicz, Lindsey Peckham, and Tina Byrne, are working to uplift the often underestimated political power of the bake sale and give it its due in both the historical register and into the future. The Bake Sale Project will feature an online library of resources, recipes, and contacts for those who are interested in using bake sales as powerful political tools, because, as Pickowicz put it, they “disrupt normative (aka rich white cishet male) definitions of ‘professionalism’ and ‘success.’” For the Culture, a forthcoming magazine celebrating Black women in food and wine, is running its own bake sale (until July 5) to raise money for the magazine’s production.

The time for this kind of action is right. “I could just donate money quietly to charities and nonprofits that I believe in, and I do,” Jonni Scott says, “but when I participate in a bake sale, I am bringing more people into the cause. They will have a story to tell. We are partnering together to fight for justice.”

Bellamy sees the bake sale as one of many means to an end. “This bake sale is different because there are 2,400 of us from around the world fighting for this one cause, and technology and the internet have made that very possible,” she says. “But I think it’s important that—even after the bake sale ends—we continue to support. Black businesses are underfunded. We need people to support us,” Bellamy says. Not just on June 20, but every month of every year.

Sticker photo by Jonni Scott. Bakers Against Racism graphic by Rob Rubba. Portrait courtesy of Auzerais Bellamy.