Some of the most riveting food writing of the 1950s took place among revolutionaries feasting on boas and canned sausages in the jungles of Cuba.

In the pantheon of modern food writers—heroes like Brillat-Savarin, James Beard, and M.F.K. Fisher spring to mind—one group has so far been neglected: Cuban revolutionaries. During the guerrilla war of 1956-1959, Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, and their bearded compañeros spent nearly two years hiding in the Sierra Maestra mountains, scrambling from one tropical hideout to the next as they fought to overthrow the sinister dictator Fulgencio Batista. With limited access to food, they were forced to get very innovative.

While reading many of their private war journals and letters in Havana’s Office of Historical Affairs as research for my book, ¡Cuba Libre!: Che, Fidel and the Improbable Revolution That Changed World History, I was struck by the loving attention the men gave to writing about food. As they chronicled new ingredients and recipes as diligently as any cookbook author, they created their own literary subgenre for posterity, one I like to think of as “guerrilla cuisine.”

The obstacles to finding a decent meal were extreme, to say the least. Cuba in the 1950s had surrendered its best agricultural land to American-run sugar plantations, so fresh produce sometimes ran short even in the wealthy capital city, Havana. Out in the provinces, refrigerators were rare, and village grocers relied on cheap canned vegetables and dried goods. By the time one got to the remote and desperately poor Sierra Maestra in Oriente Province (“the East”), where Fidel’s guerrilla uprising began in 1956, the farm-to-table menu was brief and bleak. The rebels, mostly a soft, middle-class bunch, were forced to subsist on the campesino staple of boiled malanga—taro root—mashed into a bland gruel. Their other standard repast, boiled green banana, was so dispiriting that many delicate city slickers at first refused to eat it, even when the dish was enlivened with butter and salt.

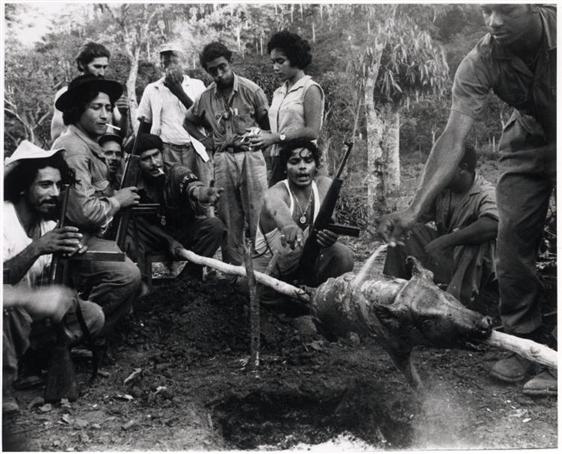

Guerrillas mingle with locals at a fiesta in 1959 (Andrew St. George papers, 1957-1990 (inclusive). Manuscripts & Archives, Yale University.)

Still, there were heroic attempts at culinary creativity. Fidel’s younger brother, Raúl, came up with a delicacy he called chorizo à la guerrilla, “sausage guerrilla-style,” sautéing a thinly sliced frankfurter in three tablespoons of honey, a squeeze of lemon, and a dash of Bacardi rum. (You can easily try the recipe at home, preferably using spicy Spanish chorizo; although a touch sweet, it makes a tasty party appetizer.) Another cutting-edge chef, Efigenio Ameijeiras, spiced up his banana mulch by foraging for wild garlic and cilantro, to acclaim from camp critics.

Roasted snake became another specialty. The recipe: Trap a ten-foot boa, then cut off the serpent’s head four inches from the neck. Hang it from a branch to drain the blood, then skin and gut. Six-inch chunks can then be roasted on sticks like marshmallows or breaded and pan-fried. The meat was sinewy and full of bones, but a good source of protein.

Not all culinary adventures were successful, especially if Ernesto “Che” Guevara was trying his hand as chef. The Argentine medic was famously austere: He happily shoveled down rotten meat with his fingers and never washed, reviving his childhood nickname, el Chancho, “the Pig.” Early in the campaign, Che purchased a scrawny cow and tried to prepare an asado, or barbecue. He stretched out the carcass on sticks like a crucifix, as he’d seen back home in Buenos Aires, but couldn’t find enough dry wood for a decent fire. Some of the meat ended up raw; other parts were charred. The next day the remains were maggoty, but the guerrillas ate them anyway. (“Only one man vomited,” Raúl noted.)

If they were lucky, a marksman might shoot a wild pig, although it, too, had to be prepared carefully to eliminate parasites. Early in the war, an undercooked pork meal provoked food poisoning. Diarrhea struck the 20 men in unison during the next day’s march. They dubbed the site La Loma de la Cagalera, “the Shitting Knoll.”

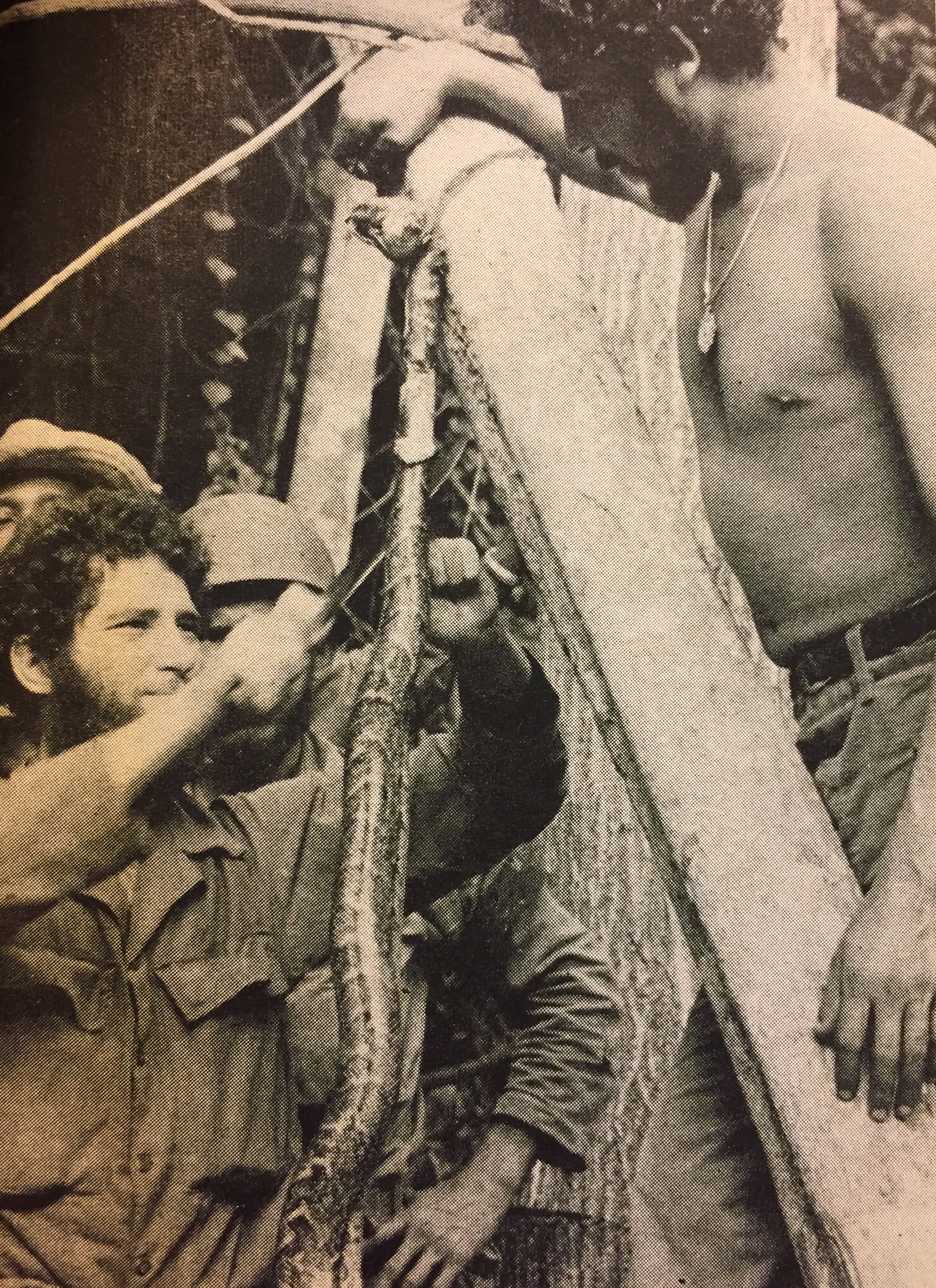

Men preparing a snake to eat in 1957 (Courtesy of the Oficina de Asuntos Históricos, Havana)

Hunger had been a constant companion ever since Fidel and 81 followers first left Mexico in late 1956 on a leaky boat called the Granma to overthrow Batista. Minutes after they left port, a raging storm convinced them to toss their supplies overboard, leaving them to gnaw on a few oranges, dry biscuits, and Hershey bars. Soon after landing in eastern Cuba, at a dismal, swampy stretch of coastline called Playa Las Coloradas, they were nearly wiped out in an ambush, but the 20-odd survivors chewed sticks of sugar cane and ate raw crabs to sustain themselves.

The hungry months that followed were when the guerrillas’ food writing was at its most extravagant and hyperbolic. In his scribbled diary, Raúl went into paroxysms of delight when a farmer brewed him fresh coffee for breakfast, ignoring the fact that the grains had to be strained through an old sock. Che wrote that the unexpected discovery of a single can of sausages resulted in “one of the greatest banquets I have ever attended.”

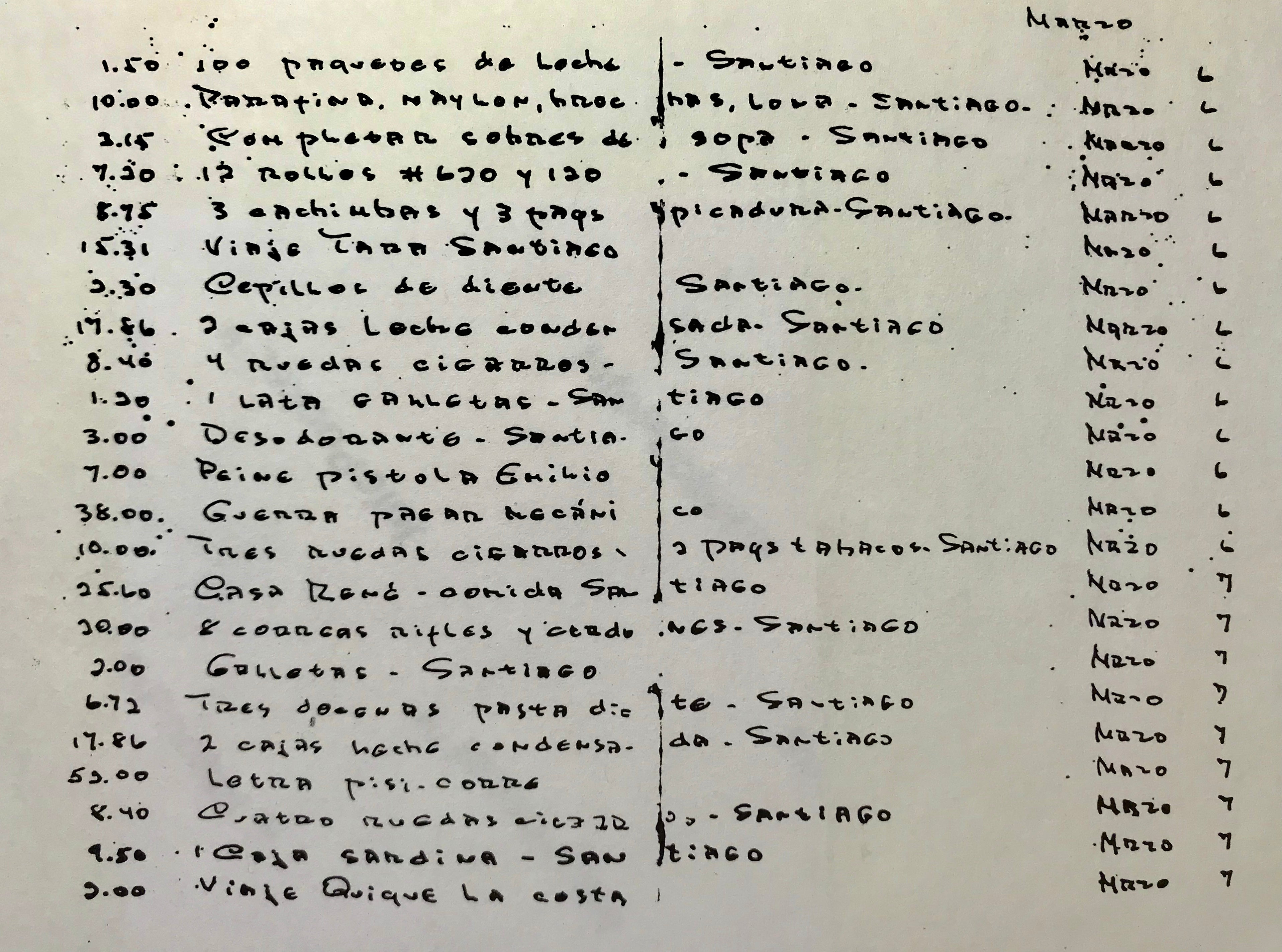

Fidel’s secretary and lover Celia Sánchez managed to have provisions smuggled on mule-back into the mountains, where they were doled out evenly between the hungry guerrillas and traded like currency: yucca for sweet potato, chocolate for cigarettes, milk for sardines. In desperate times, the truly famished might swap a valuable cigar for a single banana skin, which was then lovingly sautéed. By unanimous agreement, the most cherished treat was a can of condensed milk, which was drunk straight—with the added advantage that the containers could later be converted into booby traps. (The savvy guerrillas packed them with explosives, using chopped-up shards as shrapnel, and strung them like deadly garlands from the trees along jungle trails.)

The shortages were a source of solidarity, since officers and men shared the same rations. Even so, Fidel, a young lawyer who had grown up in a rich landowner family, had a hard time with the scarcity. He flew into a rage when he returned from the field late one night and found the rice and beans he had been expecting for dinner had been eaten. On another occasion he refused a meal because it was poorly cooked, retiring to his hammock, Che noted, “with an air of offended majesty.”

An account from March 1957 by Fidel Castro’s secretary, Celia Sánchez, of groceries sent to the revolutionaries

Fidel pleaded with Celia to send more palatable supplies and complained, “I’m eating hideously. No care is paid to preparing my food…. I won’t write any more because I’m in a terrible mood.” In another missive, his tone was openly sulky: “I have no tobacco. I have no wine. I have nothing.” Then he remembered that a bottle of decent rosé, “sweet and Spanish,” had been left in someone’s farmhouse. “Where is that?”

By the fall of 1957, Fidel’s 100-odd men were organized into six platoons, each with a cook who could improvise with limited ingredients. The situation improved radically in the spring of 1958, when Fidel moved into a hideout called La Comandancia de la Plata, Celia’s mule-back courier service became more organized, and financial donations from supporters within Cuba and exiles in the United States increased. As the guerrillas gained more territory, Fidel could enjoy fine cheeses, cognacs, tinned olives, and charcuterie—all prepared by a celebrity chef from Havana who had fled the dictatorship. But Celia’s greatest logistical triumph occurred in August 1958, when she managed to have an ice cream cake shipped on mule-back to the guerrilla camp for Fidel’s 32nd birthday, packed in dry ice the whole way. The comandante, needless to say, was delighted.

The end was clearly nigh for the dictator. On New Year’s Day, 1959, Fidel was enjoying his regular breakfast of arroz con pollo and coffee on a sugar plantation when he heard news that Batista had fled Cuba in a DC-4. A week later, he took up residence with Celia in the luxurious penthouse of the Havana Hilton. He could be seen prowling the lobby with a chocolate milkshake from the soda fountain, or enjoying succulent roast pork—the Cuban equivalent of foie gras—at the attached Polynesian restaurant.

The days of grilled snake and mulched banana were clearly a thing of the past. The future, involving Russian borscht and rock-hard Soviet pierogis, is another story.

Top photo: Andrew St. George papers, 1957-1990 (inclusive). Manuscripts & Archives, Yale University.