After 100 years, the bright and bold fusion cuisine is looking to the future without forgetting its past

To make one of Peru’s treasured national dishes, the irresistibly smoky lomo saltado, you need a few strips of sirloin steak, blistered red onions, chunky tomatoes, and aji amarillo, a mild yellow pepper common in Peruvian dishes. Here’s what else is needed: soy sauce, white rice, and a ripping hot wok typically found in classic Chinese takeout joints.

Despite what you might think, lomo saltado isn’t a viral dish trending on TikTok. It’s been a traditional staple of Chino Latino cuisine for over one hundred years. And you’ll find dozens more creative combinations like this across Latin America and, more recently, the United States.

In fact, Asian Latino immigrants—from Japanese Peruvians to Korean Argentines—total more than 300,000 in the United States. Though it may surprise no one, one of the largest hubs for Chinese Latin Americans is New York, with immigrants primarily coming from Peru, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic. In a corner of New York’s Upper West Side on 72nd Street, historic Chino Latino restaurants have been serving the community since the 1960s.

Richard “Richie” Lam is one such restaurateur in this prismatic diaspora. Lam, who owns the Chino Latino restaurant La Dinastia alongside Michael Lan, grew up waiting tables and taking orders for the same restaurant his father started in 1986. On their bilingual Spanish-English menu, it’s perfectly normal to see General Tso’s chicken or shrimp egg foo young served with a side of tender plantains. Within the walls of the restaurant, there’s a healthy mix of restaurant regulars, who summon the waiters over in Spanish and order the crackling chicken with a creamy jalapeño and cilantro green sauce for the umpteenth time. Newer to this restaurant, there’s also a crowd of diners lured in from viral TikTok’s documenting Chino Latino cuisine.

Across the country in Los Angeles, another second generation is keeping two Chinese Peruvian restaurants alive: Chifa and Arroz & Fun. Sibling owners Ricardina “Rica” and Humberto Leon are following in the footsteps of their mother, Wendy Leon, who opened up a Chinese Peruvian restaurant—also called Chifa—in 1975 before immigrating to California a year later.

Spread from Chifa

At the siblings’ version of Chifa, which opened in 2020 in Eagle Rock, they serve lomo saltado alongside traditional Chinese and Taiwanese dishes like zongzi and dan dan mian. Their daytime cafe Arroz & Fun, located in Lincoln Heights, followed in 2023, serving bolo bao breakfast sandwiches and chinchurro, a Chinese donut flecked with cinnamon sugar. Although Rica Leon, who is the CEO of Chifa, would never call any of her restaurants “fusion,” she understands how this idea is central to traditional Peruvian fare. “I would say Peru was probably one of the OG fusion [cuisines],” Leon says. “What people traditionally identify as Peruvian food, like lomo saltado? All of that was invented because of Chinese immigration.”

Indeed, Chinese workers have been in Latin America for hundreds of years. As early as the 16th century, Chinese workers were imported to Latin America to toil in the guano pits as enslaved workers, crew members, and prisoners. Even after slavery was toppled in Latin America in the mid-19th century, governments began soliciting indentured servants from Asia, especially China, the Philippines, and Japan.

Though many Chinese immigrants became indentured servants, there was a silver lining: the promise of home-cooked Chinese food. Chinese workers successfully advocated for contracts that ensured daily access to Chinese food and rice, says Lok Siu, a UC Berkeley professor of ethnic studies who has written extensively on the Asian diaspora in Latin America. This meant that Chinese chefs accompanied and fed countless workers in Latin America. At the same time, around 70% of these Chinese chefs began working for elite families in Peru, who saw their cuisine on par with the coveted tastes of France. This too helped cement Chinese cuisine’s indelible mark across Peru.

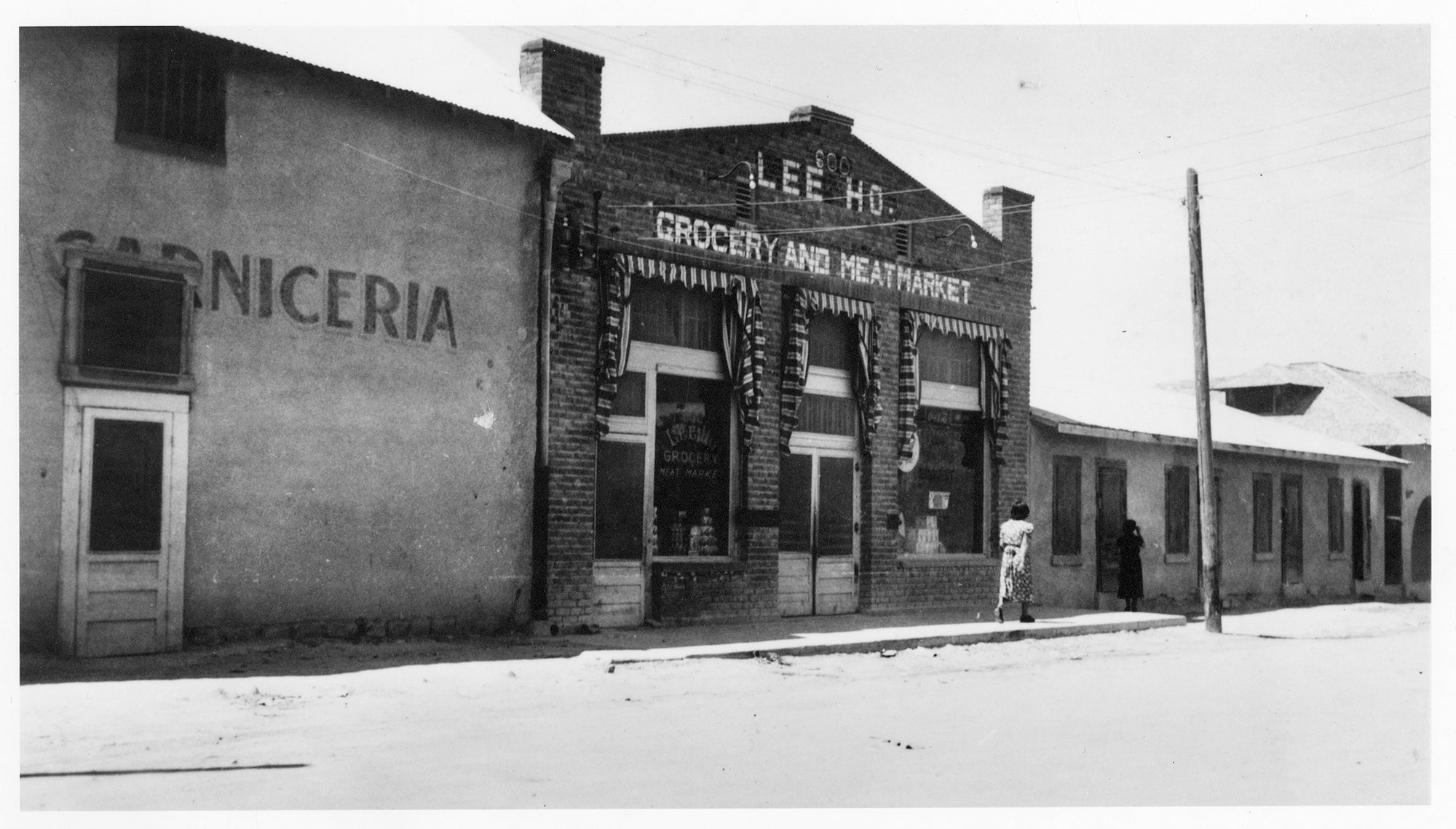

Chinese Chorizo Festival / South Tucson Chinese grocers

It was also during the mid-19th century that major Latin American cities and border towns emerged as lively hubs for Chinese communities. Chinatowns such as Havana’s El Barrio Chino and Mexicali’s La Chinesca constructed a host of new buildings, retrofitted with ceramic-tiled pagoda roofs and brilliant shades of green, yellow, and red. To serve this rapidly growing population, Chinese storefronts opened and began selling everything from groceries and deli meats to hot prepared lunches. In Lima, these were called “chifa,” the Peruvian word for Chinese restaurant. “There was a proliferation of different food sales institutions serving chifa that realized there was a need,” says Siu. The food initially catered to the tastes of Chinese workers, but soon enough, these counters became popular among Peruvians too.

Quite different from the expansive Chinese menus we know today, these takeout stalls operated with a limited set of dishes. Most sold Chinese dishes separately from Latin foods to appease various customers. But the openness of the menu also encouraged more experimentation. Chefs, both Chinese and Chinese Peruvian, began toying with dishes depending on ingredients available to them. At some Peruvian stalls, chefs began intermingling traditional Peruvian recipes alongside flavors of traditional Chinese dishes. What began loosely as experiments—Chinese techniques like wok stir-frying combined with Peruvian ingredients like chile peppers and heirloom rice—evolved into dishes central to the chifa canon: arroz chaufa, a fried rice dish sometimes cooked with sweet plantains and Peruvian dried meat; tallarín saltado, Peru’s sautéed spin on chow mein; and, of course, lomo saltado.

These recipes could have remained tethered to Latin America, but a few notable events brought this rapidly evolving cuisine to the United States. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 barred Chinese immigrants from entering the United States, which encouraged an initial migration to Latin America. The second was the Cuban Revolution in 1959, which forced many Chinese Cubans to flee the country and find jobs as sugar workers, cigar rollers, or restaurateurs in New York and Miami, according to Siu. Soon after this wave, immigrants from Peru, Venezuela, Nicaragua, and more followed and created their own spins on Chino Latino food.

For a cuisine as young and novel as this one, a new fleet of chefs has begun to learn its history and stir up their own versions of Chino Latino food. In Los Angeles, you’ll find One Hot Minute, a Chinese Peruvian fusion pop-up run by Cesar Moran and Sarina Ho, a married couple who are Peruvian and Chinese American, respectively. While growing up in Lima, Moran remembers trekking every week to chifas for a family meal of arroz chaufa and barbecue pork. Conversely, Ho didn’t grow up with much Peruvian food. But her first bite of lomo saltado sparked an immediate reaction: “It tasted so familiar but not, at the same time.”

Since launching One Hot Minute in 2020, the duo has dished out mushroom fried rice aji verde alongside house-made taro chips. Most notably, they serve a tacu-tacu patty concocted from canary beans and cauliflower rice, which gets dipped in a tingly medley of Sichuan spices. The sandwich pays homage to Moran’s favorite Peruvian dishes and Lima’s most popular sandwich shops, many of which are owned by Chinese or Chinese Peruvians.

Others have found the path to Chino Latino cuisine much later in life. The chef and artist Feng-Feng Yeh grew up in Tucson, Arizona, but didn’t learn about the Sonoran Desert’s history of Chinese immigration until visiting the Tucson Chinese Cultural Center in 2020. These eye-opening visits compelled her to launch the Chinese Chorizo Project to commemorate the region’s Chinese Mexican grocery stores, many of which closed in the ’70s and ’80s.

You’ll also find hubs of Chino Latino restaurants sprinkled across America, both cult favorites and new spots alike. A Chinese Mexican takeout in Phoenix, Arizona, called Chino Bandido has dished out bespoke rice bowls with carnitas, egg foo young, and jerk fried rice for over 30 years. Meanwhile in Cincinnati, Ohio, there’s Lalo, a Chino Latino restaurant opened in 2017 by partners Tobias Harris, Trang Vo, and Eduardo Reyes that whips up their own version of lomo saltado alongside Mexican bibimbap and Cubano-style banh mis.

Christine Lau didn’t grow up with classic Chinese American joints serving crab rangoon and sweet and sour pork in Oakland, California. But upon moving to New York City in the early 2000s, she began immersing herself in the Chinese takeout scene and scoping out her favorite Chinese Peruvian chicken joints across Queens. These formative experiences, as well as visits to Chino Latino institutions such as Flor de Mayo, Calle Dao, and New Apolo, ultimately inspired her menu at Chino Grande, a Chino Latino restaurant in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

There, you’ll find salchicha arroz chaufa, a fried rice dish with longaniza, lap cheong, and chorizo next to asopao congee croquettes. The sauce caddy, a trio of ramekins with green sauce, ketchup, mayo, and spicy duck sauce, is her ode to all the traditional sauces eaten with Chino Latino food. Ultimately, with her Chino Grande menu, Lau hopes to channel the same spirit as old-school Chino Latino joints: “I would love it if we became your Chinese takeout spot,” she says.

For all the innumerable variations of Chino Latino cuisine in the United States, there’s one thing that unifies them all: an understanding about the fluidity of cuisine and an instant connection to the communities cooking the food. As Leon talks about her family’s immigration, it’s clear that her devotion to Chino Latino food runs deep, solidified through family trips back to Peru and the stories she passes down to her children. These days, Leon feels most energized whenever she shares her food with fellow Chinese Latinos and sees their faces light up in the plush teal booths of Chifa.

“They’re so happy to have those flavors they remember from their childhood, and having Chinese food and Latin food in one location,” Leon tells me. “They bring their grandmother, they bring their mother. It makes us really excited when we see that.”