The singular stand-up comedian instructs in the art of the very, very long meal

I met Jacqueline Novak for an early dinner at Il Buco on Bond Street. A 5:30 p.m. seating may not be a prime reservation at this buzzing NoHo trattoria, especially for a comedian whose new Netflix special has been deemed “mind-blowing” by the Los Angeles Times, but it served our purpose: to enjoy the parade of prosciutto and wine that defines a fantastic restaurant experience as long as physically possible.

Our mission on this drizzly January evening was inspired by a moment from an episode of Poog, the nominally wellness-focused podcast Novak cohosts with eccentric comedian and actor Kate Berlant, called “The Mushroom Fog Hut.” In it, Novak expresses skepticism toward modernist cooking techniques where the execution becomes the main attraction, obscuring the food. “Instead of serving me a tiny mushroom terrine,” she says, wildly fantasizing, “the molecular gastronomist pumps air into something in such a way that I get to eat the mushroom terrine in the form of a cloud for…ten minutes.” Then she delivers her thesis: “Those who know me know that I’m always looking for duration in food.”

This struck a chord with me. As a frequent cook, I’m regularly dismayed by the ratio of time spent cooking to time spent eating. Thanksgiving is perhaps the most egregious example of this—a meal that takes three days to cook takes 20 minutes to consume. While cooking can be a labor of love, dining out is all love and no labor. Like Novak confronted with a plate of nachos, I wanted to dive deeper into the pleasures of a drawn-out dinner.

Novak’s latest work, a Netflix comedy special titled Get on Your Knees, is not about restaurants—it’s a fast-paced, high-minded, 90-minute rumination on oral sex. Specifically, as she explained on Late Night with Seth Meyers, “the kind related to the cylindrical object.” Food is also not the sole subject of Poog. But you are here reading about Novak’s brilliance in a food publication because this stand-up comedian with a special about blow jobs and a podcast largely about skincare is one of the most honest—and underrated—voices in food today.

In a world saturated with food content, Novak’s enthusiasm feels novel. It’s neither in-the-know restaurant commentary nor a rejection of it.

Novak approaches her love of eating with intellectual rigor and a passion best described as pleasantly manic. In a Poog episode titled “The Uppermost Pringle,” she and Berlant begin a discussion about elevator pitches and arrive at the Seinfeldian conclusion that “because the top Pringle carries nothing, it does not realize it too is being carried.” As they explain, the “sacred geometry” of Pringles allows each chip to support another—without a friend to uphold, the top chip lives a lonely existence. (If these concepts seem unrelated, I suggest tuning in to the podcast—the journey is worthwhile.)

In one stand-up set, Novak describes the erotic implications of chicken-wing-eating techniques, noting that anything other than a perfectly clean bone “makes me wonder, are you going to leave meat on me too later?” In another, she explains her reluctance to share a side of fries with friends who order salad, saying, “You made your bed of lettuce, and you deserve to lie in it, hungry.” Her jokes, and her appetites, are insatiable. In her mind, there’s never enough pizza at a pizza party, no French fry can be spared, and nachos are best eaten in the sanctity of one’s own home (so that you can kick them into your mouth, “hacky-sack-style”).

In a world saturated with food content, Novak’s enthusiasm feels novel. It’s neither in-the-know restaurant commentary nor a rejection of it. She doesn’t name-drop chefs, defiantly profess loyalty to lowbrow snacks, or drink out of plastic quart containers to channel The Bear (or the legions of line cooks who hydrate this way). She simply describes the nature of craving food in language that ranges from poetic to carnal.

Over lightly fried sardines and berbere-spiced rabbit chops, Novak explains that she sees restaurants as interactive theater—food, fellow patrons, and presentation are all elements of the show. Our conversation was momentarily sidetracked as she joyfully noticed wax pooling at the base of a candle on our table, exclaiming, “Is this a real candle? Let the place burn. We will go down.”

After apologetically requesting a margarita (not a classic pairing with Italian food, but the heart wants what it wants), she described a sense of ease, saying, “It’s almost like the brain is static electricity—you can kind of dampen it [with] food, dining, and a little bit of ritual.” Novak’s work is characteristically anxious and discursive. To her, the theater of dining provides an easy way to be present with others. She elaborated, “It almost leaves just enough room for a reasonable amount of the mind.” Conversation can flow once cocktails are on the way.

In her mind, there’s never enough pizza at a pizza party, no French fry can be spared, and nachos are best eaten in the sanctity of one’s own home.

While an ecstatic escape is delivered at restaurants, at home it must be seized by force. Novak isn’t pretentious about what she cooks, often favoring takeout or prepared meals from a home delivery service (Factor75 is her go-to). She describes feeling liberated when she privately breaks the perceived rules of food. A classically elegant treat—say, a carefully plated crostini—is just one more task to plan and execute. Instead, Novak prefers to strip her snacks of all fanfare. As an example, she detailed a defiant ritual she employs in moments of anxiety: “There’s something for me about grumpily, poutily grabbing a stack of, like, low-carb tortillas and maybe a piece of cheese crudely grabbed from the plastic. I march over to my couch, throw a blanket over myself heavily, and then under it, like a little squirrel, I munch on my stack of tortillas…for some reason, that feels like revenge.” To Novak, this primal approach to “intuitive eating” is a form of self-love, satisfying both emotional and bodily needs.

Now is perhaps the time to mention that, although Novak’s appreciation for restaurants borders on reverence, she is not, in the strictest sense, a foodie. Her quest for dinner is not motivated by seeking out hard-to-get reservations or tasting menus. At home, she visits the places she loves time and time again. On Poog, she and Berlant endorse unfussy restaurants and old Hollywood classics—preferences that have occasionally confused followers. Friends and listeners have flocked to Jar, one of Novak and Berlant’s mainstays in LA’s Beverly Grove neighborhood, and been surprised to find a decades-old, oak-paneled steakhouse instead of a modern, Instagram-friendly establishment.

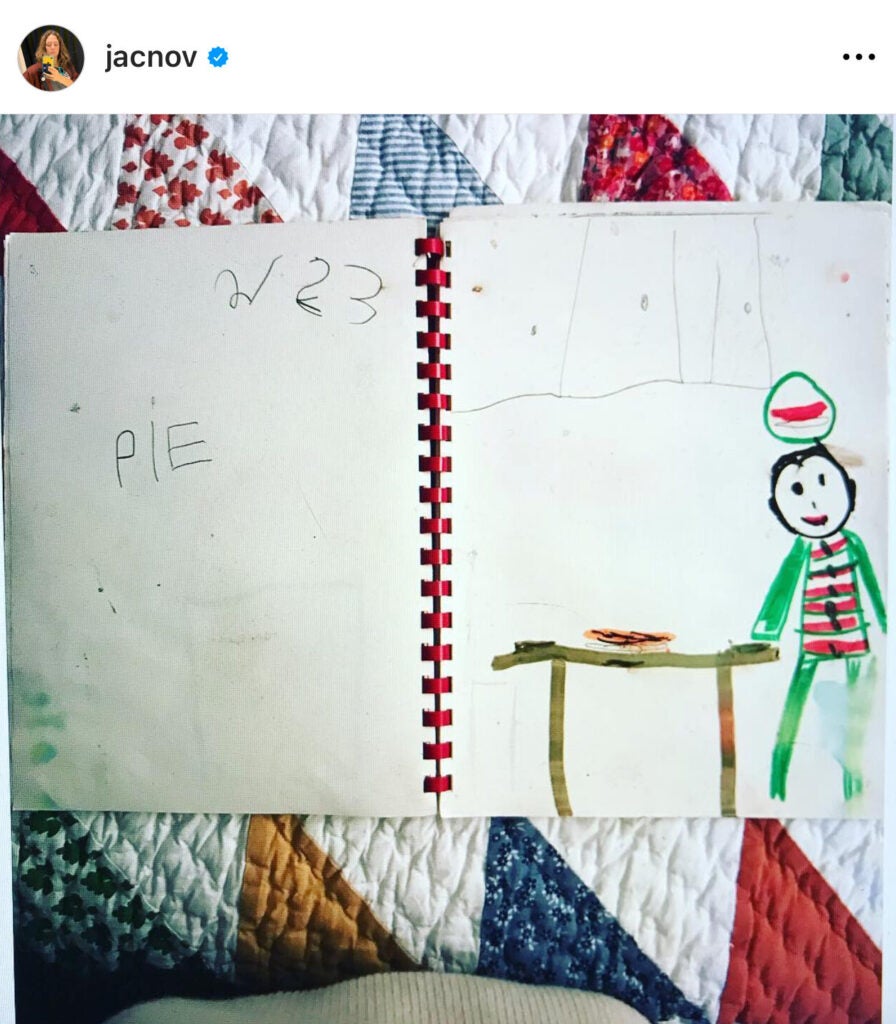

She explains, “It’s such an argument for being behind on culture. Make sure you’re behind on culture, and that way you can enjoy your life.” For a chronic overthinker, skipping the noise of the restaurant scene provides relief. To underscore this simplified approach, Novak described a drawing that she created in kindergarten. It depicts a man standing in front of a table and a simple illustration of a pizza. A thought bubble floating near the man’s head displays a second rudimentary pizza drawing. In her view, “It’s just on the table, and it’s in his mind, and that is basically my work. It’s certainly what I have to say about food.” Novak doesn’t aim to critique the dining experience. Instead, her work provides a full-throated endorsement of eating in general.

To brag just a little, I’d like to note that we achieved our goal. By ordering generously and chatting enthusiastically, we were able to savor our early dinner until we were (very politely) asked to make way for the next group at 9:30. At the end of the evening, the benefits of a prolonged meal were clearer than ever. A truly long-ass dinner is not only a gateway to good conversation, it’s also a form of theater, a cultural study, and a good excuse to order two desserts.