The practice of eating dog meat is at the center of many racist stereotypes about Asians. Is it possible to reexamine both the stereotype and the practice?

For East and Southeast Asians living in the West, especially for those of us who were born here, very few ingredients remind us of our precarious sense of belonging as much as dog meat. We Asians have probably all been asked at least once, perhaps with the inquirer’s index finger pointed suggestively at our banh mi or Caesar salads: Is that dog? Is it true you eat dog?

Here are the answers we tend to give in sensitive East-meets-West moments like these: No, never, it’s an archaic practice; it’s a poor-people thing; it’s a myth. But the more complicated answer is that we come from diverse countries—South Korea, Vietnam, China, the Philippines—where people eat all kinds of regional delicacies that are unknown to the Western palate, not because of poverty or barbarism but simply because they enjoy them. We don’t often speak to this nuance because the stereotype has been so damaging that even the discussion feels like a game of hot potato. We do this rhetorical dance because of how the practice of eating dog has been wielded in the past to exoticize and demean us as heartless monsters who wouldn’t blink twice at barbecuing man’s best friend.

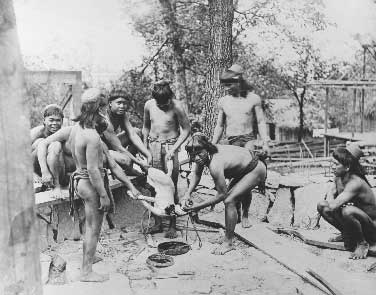

During the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, the Philippine Exposition’s major draw was an artificially replicated village featuring a group of “primitive” Igorot people grilling dogs on site. Unsurprisingly, this became an object of both scandal and wide fascination. The United States had just won the Philippine-American War two years prior, so exhibiting these people and their culinary habits was a way of celebrating the civilizing effect America was having on the Philippines.

At the time, the St. Louis Republic reported, “After nearly two weeks of enforced fasting from puppy steaks and dog soup, the famished head-hunters are at last to be regaled with their cherished viands…. Six dogs have been obtained, where or how is kept a dark secret and the dog-killing time is contingent on how soon the canine victims shall have been fattened for the feast.” Spectators viewed the reconstructed village aghast yet relieved that their own country was rapidly whipping the Philippines into shape.

Igorot people at the 1904 St. Louis World Fair (photo: St. Louis Public Library)

In 1989, as the United States welcomed refugees from Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, a dog-eating incident involving two Cambodian men in Long Beach sparked national outrage and a new California law that made it illegal to use any animal “commonly kept as a pet or companion” for food. In an interview with The New York Times, Vu-Duc Vuong, then executive director of the Center for Southeast Asian Refugee Resettlement, said, “There have been very few, if any, instances of pet eating. Far more numerous are anti-Asian prejudices and violences based on no more than false or racist stereotypes of Asian Americans.”

As recently as 2016, an Oregon senate candidate suggested that taking in Vietnamese refugees was a mistake because, in his words, they were “harvesting people’s dogs and cats.” Dog eating has always been political for us.

When I asked Clarissa Wei, senior reporter for Goldthread, a digital publication focused on Chinese food and culture, what she thought about dog eating, she acknowledged the controversy. “Westerners have a tendency to see Chinese people as a monolithic mass,” Wei, who is based in Hong Kong, wrote via email. “The people who do regularly consume dog meat are a small minority in a country with a population of 1.379 billion. Yet ‘dog-eating’ is a dominant topic when it comes to the Chinese.”

Because of how the West has obsessed over the practice as a foreign taboo, having a nuanced conversation about dog meat in mixed company is a challenge.

“If anything, eating pig meat or chicken meat or cow meat should warrant the same outrage as dog meat,” Wei wrote. She admittedly can’t personally stomach it, but it’s fairly obvious that the dog is viewed as exceptional for people who aren’t normally animal-rights activists.

Last year, a bipartisan group of congressional representatives introduced a resolution (H.R. 30) condemning the infamous annual Lychee and Dog Meat Festival in Yulin, China. If passed, it would be the first time Congress has made a legislative statement about animal welfare practices overseas; the cosponsors plan to introduce more legislation calling for a worldwide ban on the dog and cat meat trades.

Throughout Asia, the practice of eating dog has been a locus point regarding generational differences, class mobility, and the seriousness of Western scrutiny. During the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, South Korea, earlier this year, various news outlets and social media posts put a spotlight on the practice. Alex Paik, managing director of AP Communications, a company that promotes Korean culture, was firm in his response to my queries: “The vast majority of Koreans are grossed out at the thought of eating dog,” he said. Since the Korean War, he told me, the perception of Koreans as enthusiastic dog eaters has haunted them. The truth is, those who embrace the practice have always been a minority: Most Koreans, he wrote, are firmly in the “dogs are pets” camp. “Usually we hear about some older folk who believe in it having special, revitalizing properties.”

“The people who do regularly consume dog meat are a small minority in a country with a population of 1.379 billion.”

Among Vietnamese people, the practice of eating dog meat is a bit harder to shove into a box and stow away, though we also keep that acknowledgement to ourselves. When I was a kid, my mom would joke that our five-pound Chihuahua, Bambi, wouldn’t make a very good meal if the pantry came up empty: “Maybe one sausage,” she’d say. But actually, my family, from the seafood-crazy deep south of Vietnam, aren’t dog-eaters anyway: It’s always been something that we make fun of Northerners for. It made sense to me that, since the majority of Vietnamese immigrants to the West are from the South, we don’t actually know much about the practice. So I called up Andrea Nguyen, renowned author of many pan-Asian and Vietnamese cookbooks and child of northern Vietnam, to have that frank conversation I’d been seeking.

“My dad would tell me, ‘Look, if you smell dog grilling, it’s so fragrant it’d make your mouth water,’” she recalled. There’s a sensory pleasure in fire-roasted dog meat—from the mahogany skin, rendered fat, and pungent aromatics—that activates nostalgia in people who grew up with it as just another potential protein source, like pigs, chickens, and geese, Nguyen told me. But it was a particular kind of dog, a type that isn’t normally considered a pet. “It’s not like we’re going to watch the Westminster Dog Show and only see a dinner buffet!” she said, laughing.

Nguyen has never eaten dog, but her parents enjoyed it so much that, on special occasions, her mother would make mock dog stew in their home in Southern California. She’d buy a whole, skin-on pork leg, wrap it in paper, and throw it in the fireplace. “The burning would mimic the smoky flavor they missed, and the ratio of fat to meat to skin in the pork leg is apparently spot-on,” she said. Her mother would flavor the stew with galangal, turmeric, and mam tom, the fermented shrimp sauce.

For Nguyen, mock dog stew was just a tiny, delicious part of her childhood—it wasn’t particularly scandalous or desperate. But she’s been asked about dog meat so often, she’s sick of it. “Why the fixation on this outlier?” she asked. “There are so many other beautiful things in our cuisine.”