How did we get from grilled eel to sweet onion chicken teriyaki sandwiches?

Consider Subway’s Sweet Onion Chicken Teriyaki sandwich. “This gourmet specialty is a flavorful blend of tender teriyaki glazed chicken strips, served hot and toasted on freshly baked bread,” boasts the menu. Teriyaki originated as a simple Japanese grilling technique from around the 17th century. So how did it get from there to an adjective that can be tacked onto fast food menus? What is going on here?

“Teriyaki” is a word that has been so incorporated into American lexicon that we almost forget when it wasn’t—like “kindergarten” or “paparazzi.” The same goes for its flavor. Burgers, ribs, and chicken wings in midrange chains all over America drip with sticky, sweet “teriyaki sauce,” just another flavor profile to choose over “southwest” or “Italian.” It inhabits the tricky space between cultural appropriation and cultural transformation. On one hand, the Sweet Onion Chicken Teriyaki is a bastardization of Japanese culture, decontextualized and repackaged so many times that it no longer resembles what it once was. On the other, it’s an example of adaptation, of how immigrants made do with the ingredients they had and ultimately created something new.

Teriyaki in the original sense is a technique, in which a glaze is applied in the last stages of grilling various meats like chicken and fish. In Japan, it’s most often a combination of soy sauce and sake or mirin, a sweet rice wine, which are boiled together until they reduce to a thicker basting liquid. The combination of the reduction and the heat of the grill caramelizes the sugars and gives the meat a punch of sweetness and umami. Sometimes sugar is also used in the sauce, but there is enough in mirin to caramelize the meat on its own and to achieve a thick reduction. The sauce is typically brushed on grilling or broiling meats, which are served on skewers, or over rice like with unagidon, a dish of grilled eel.

The translation from this to plastic bottles of sugary, ginger- and garlic-filled marinades is murky, but Hawaii was one stop on the route. The first Japanese immigrants to Hawaii were brought over in 1868, to work on the island’s main export—sugarcane. Historian Rachel Laudan says that by the 1920s and 1930s, teriyaki on the island looked very different from how it did in Japan, thanks to influence from native Hawaiians and other immigrants. “People began substituting sugar for the sweet mirin, which makes sense on an island where they grow sugarcane,” she says. “Then ginger and green onion was added, and sometimes garlic as well. Those may be Chinese influences, since they don’t seem to crop up in Japan.”

Teriyaki “is the answer to the European demi-glace,” Sam Choy, chef and author of multiple cookbooks about Hawaiian cuisine, told me. “As it came across the water it was very unique, it was very exciting, it had the wow factor. But more importantly it was really easy to make.” Because of that, it became a staple of the island’s “plate lunch” (a plate usually consisting of potato macaroni salad, rice, and an entree like teriyaki meat or chicken katsu) and the classic marinade for Hawaiian BBQ. According to Choy, the basic Hawaiian teriyaki is soy sauce, sugar, and ginger, with maybe some garlic and a little cornstarch to give it more shine, already a far cry from the Japanese basting sauce.

Teriyaki may not have become so ubiquitous in America if it weren’t for the post-WWII obsession with all things “Polynesian.” Not only were white Americans basking in middle-class comforts, but many had just returned from tours in the South Pacific and were looking for ways to re-create the flavors of the islands at home. Teriyaki was the 101-level flavor that helped this happen—savory and sweet, not too “exotic,” but just interesting enough for white people. Chains like Trader Vic’s and Don the Beachcomber, which traded on their “tropical” decor and menus, thrived, and served dishes like egg rolls, crab Rangoon, and teriyaki beef. The 1955 Ford Treasury of Famous Recipes From Famous Eating Places lists a recipe for “Beachcomber Cantonese Spareribs” from the eponymous restaurant, which was marinated and basted in soy sauce, sugar, salt, and ketchup—essentially American teriyaki.

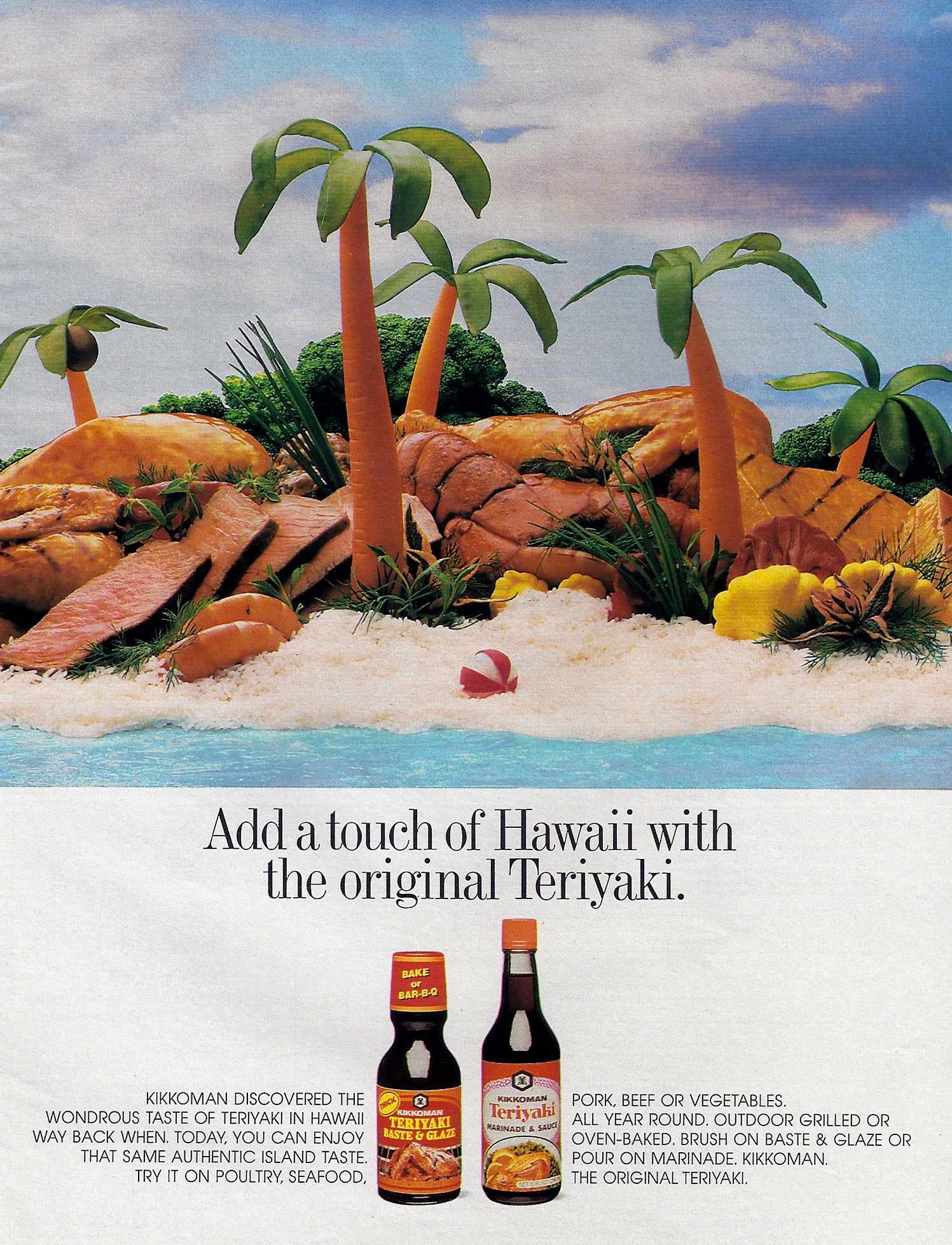

It helped that both soy sauce and sugar were pantry staples by the 1960s, but soon teriyaki became even more accessible. In 1968, Kikkoman, which had become nearly a household name to Americans already long familiar with soy sauce, introduced a bottled teriyaki sauce. In 1972, they opened a factory in Wisconsin (the first Japanese manufacturing plant in the country) to capitalize on the cheap soy and wheat available in America, allowing them to produce even more. Soon teriyaki didn’t even need to boast Japanese origins. Soy Vay, a popular line of bottled “Asian” sauces and marinades, was founded in 1982 when Eddie Scher, who is Jewish, and Heidi Chen, who is Chinese, met at a potluck at Humboldt University in Arcata, California. Their “Very Very Teriyaki” is the second most popular teriyaki sauce in the country. According to a Simmons National Consumer survey, the average American has a bottle of teriyaki sauce in their kitchen, and “2.25 million Americans used four or more bottles/cans/jars” within 30 days in 2017.

Americans have a fetish for the authentic. As a nation of mostly people from other places, we tend to be insecure about our tastes, swinging between worrying we’re getting it wrong and being defiant in our wrongness. American pour-on teriyaki sauce is in no way authentic…to Japan. But it’s become American in its own right, a synthesis of cheap, satisfying ingredients that can absorb and adapt. In that way, the Sweet Onion Chicken Teriyaki might be the most American sandwich.