Way, way before there was “California cuisine,” there was the original California cuisine—a fusion of Spanish, Mexican, and native foods.

Marianne Partridge is making California-style cheese enchiladas in her home kitchen in Rancho San Julian, in Central California. A tall stack of flour tortillas sits on her counter, ready to be lightly fried in a pan of vegetable oil. Her kitchen’s small table is piled with the sliced onions, crumbled queso seco, and canned, pitted black olives that will fill the tortillas. A homemade sauce of pureed Anaheim and Pasilla chiles bubbles away on the front burner of a white 1950s Wedgewood stove. Marianne’s oven is also full, stuffed with trays of beef-filled empanadas studded with sherry-soaked raisins, more black olives, and pine nuts.

Both of these dishes were adapted from recipes in an old notebook that once belonged to Mercedes Poett, Marianne’s grandmother-in-law, who wrote them down in the early 1900s. Marianne began cooking from these recipes four decades ago, when she married Jim Poett, a seventh-generation cattle rancher, and moved with him to the family’s 181-year-old ranch near Santa Barbara, on California’s Central Coast. The notebook was a trove of family history, as told through the recipes that the women of the family were eating and cooking in the ranch’s early years. And Marianne found that many of them have an important ingredient in common: black olives. “Olives are the sign of a California-style recipe,” Marianne explains to me as she juggles a variety of jobs, taking phone calls from the local newspaper (where she is the editor), improvising a recipe for tomatillo salsa, and arranging homegrown flowers in cans to decorate the table for the feast she is cooking for the two dozen friends and neighbors who are on the ranch to help brand the family’s cattle today. “If you see olives in a recipe for enchiladas or tamales, you know it’s from here.”

California cooking has been known for many things over the years: ’70s-era carob bars and sprout-filled sandwiches; Alice Waters’s and Jonathan Waxman’s “California cuisine,” which first bloomed in the Bay Area and introduced Americans to the idea of cooking focused on local, sustainable, seasonal ingredients, fueling the organic and farm-to-table movement; Roy Choi’s Korean-Mexican fusion served out of trucks and in cool spaces in Los Angeles. But the state’s first fusion foods evolved back in the 18th century, when the Spanish began to establish a colonial presence and built a string of missions up and down the coast. For the next 100 years or so, the land around these missions was divvied up into ranches and granted to a new landowning class of “Californios,” who raised cattle to feed the soldiers and the local presidios, or forts.

These settlers and their families were largely cut off from the rest of the Spanish empire, around 1,500 miles stretching from Mexico City and separated by the high Sierra Nevada and the deserts of Baja California. While their counterparts in places like Texas and New Mexico maintained relationships with family and community in the cities of central Mexico, the Californios—through isolation and the unique attributes of their environment—developed their own culinary traditions, fusing elements of Spanish, Mexican, and native cooking.

Surprisingly, most Californians today know very little about the state’s original style of cooking. I grew up in Santa Barbara, a city full of Spanish-style buildings that hosts an annual weeklong party known as Old Spanish Days. But while I watched flamenco and learned about the history of the missions and the city’s founding families, I knew nothing about their culinary legacy and the dishes of fideos (Spanish noodles), sweet squash empanadas, and omelette-like “tortillas” that are still eaten by some of their descendants. If I hadn’t become friends with Marianne’s daughter, Elizabeth, and spent large chunks of my childhood on the ranch, I might never have heard of these old dishes.

Fortunately for those of us who don’t hail from one of the state’s oldest families, Marianne’s is not the only old Californio clan that kept notebooks full of historic recipes. Over the past 100 years or so, a handful of women have published collections of Californio recipes, giving the rest of us a glimpse into this style of cooking. Recently, when I moved back to California (my first time living in my home state as an adult with my own kitchen), I dove into these old books, hoping to discover what made the state’s original foods unique.

My first surprise was how decidedly Spanish many Californio recipes are, despite the fact that the foods in Mexico at the time had already begun to resemble the classic Mexican cuisines we see today. The missionaries who made their way north to Alta California found a land strikingly similar to Spain, with a temperate, somewhat arid climate perfect for traditional Mediterranean crops. The padres established large orchards of olive trees to make oil, while oranges, grapes, almonds, and figs brought directly from Spain thrived in the mission gardens more easily than anywhere else in the empire. The countryside was divvied up into large ranchos dedicated to raising cattle to feed the soldiers stationed in the presidios. And many of the region’s settlers also came to the area more or less directly from Spain, rather than from colonial Mexico, bringing their traditions with them.

As a result, many Spanish dishes were incorporated relatively unchanged into the local diet, and many more retained Spanish flavors. In La Cocina Española, or The Spanish Kitchen, by Encarnación Pinedo, the earliest known collection of Californio recipes (published in Spanish in 1898), the roster includes membrillo (quince jam), empanadas flavored with traditional Spanish fillings, like raisins, and dishes made with Spanish salt cod. Almonds, walnuts, and even hazelnuts are used extensively. Saffron also makes an appearance, as does sherry and, of course, olives.

The Spanish influence can also be seen in the fact that Californio recipes usually call for olive oil, rather than the lard popular in Mexico. And perhaps most surprisingly, most of the original recipes call for wheat tortillas, rather than the corn tortillas that are now a staple in every California kitchen. According to the food historian Rachel Laudan, the preference for wheat didn’t arise just because the grain grew well in Northern California. “As far as the upper class was concerned, they were very slow to adopt New World ingredients in general. They stuck with wheat, not maize,” she says. (Laudan also points out that the title of Pinedo’s book, “The Spanish Kitchen,” was a class signifier. “‘Spanish’ had a couple of different meanings: One is that you were born in Spain, but another is that you were upper class, and that might or might not mean that you were ethnically Spanish.”)

Of course, whether they saw themselves as Spanish or not, California’s colonists did adopt some ingredients from Central and Southern America and cultivated corn, tomatoes, squash, pumpkins, and chiles. (Chocolate, perhaps the most beloved ingredient, wasn’t suited to California since the cacao plant could not be grown there, so soldiers brought it with them as part of their government-issued rations.) Pinedo’s recipes include many Mexican-style dishes, including tamales and chile rellenos, and fusion dishes that likely have roots in other parts of New Spain, like empanadas filled with sweetened pumpkin. The California Mexican-Spanish Cookbook, published in 1914 by Bertha Haffner Ginger (a schoolteacher who worked in California for a few years), focuses more on these fusion recipes, like enchiladas filled with chicken, hard-boiled eggs, raisins soaked in sweet wine, and olives, and a soup of beans stewed with tomatoes and chile and served with Spanish-style meatballs.

Beans were a particularly popular food in early California, in part because they could be grown in the drier areas of Central and Southern California, where there was less rain than in the north. “I would call [the Californios] the ‘bean eaters,’ like the Tuscans,” says Jaqueline Higuera McMahan, another descendant of an old Spanish-Californian family. “Beans were there every day to go with the flour tortillas.” Her cookbook, California Rancho Cooking, includes creamy stewed pink beans and refried beans, made from the leftover beans from the day before. Haffner Ginger’s book records bean salad, bean soup, baked beans, and beans with melted cheese stirred in. And Pinedo’s book even includes bean-filled empanadas sweetened with sugar and flavored with cinnamon.

Some classic Californio foods may have also evolved from those of the region’s native people. Once settled, the Spanish adopted some of the local foods eaten by native Californians, including mint, purslane, bay leaves, wild anise, and local fish. According to Margo True, the food editor of Sunset magazine, Santa Maria–style grilling—a method of grilling meat over wood coals that is popular on the Central Coast—may have roots in native cooking. “The thinking is that the very first instance of this style of cooking originates with the Chumash,” True explains, referring to the region’s native inhabitants. “One of the elements of indigenous cooking was impaling hunks of meat on green willow rods and laying them over pits of open flame. And there was another style of weaving willow rods to form a grid and laying that over open flame—which, you know, is a grate.”

Over the years, some of these original Californio recipes have evolved into dishes that became popular outside of this cooking tradition. True suspects that tamale pie—a baked casserole of meat (usually beef) and vegetables covered in masa, the kind of prepared cornmeal dough used to make tamales and tortillas—may have been a California invention, the product of rapidly industrializing Californians meeting old Californio families. Sunset magazine published more than 50 different versions of the recipe between 1920 and 1980, and Bertha Haffner Ginger also records a recipe for tamale pie. (Another innovation recorded in Ginger’s book: an avocado salad made up of nothing more than a half an avocado seasoned with salt and sugar and served on lettuce with a dressing of lemon juice and olive oil—a decidedly modern-feeling California dish.)

But for the most part, the original recipes cooked by Californios stayed within their families, handed down generation after generation, and remained fairly consistent in their methods and ingredients. A few years ago, Elizabeth Poett, Marianne’s daughter, began her own version of her great-grandmother’s notebook, filled with the recipes her family loves and the dishes she has learned from her mother and others over the years. She particularly loves her great uncle A. Dibble Poett’s recipe for stewed beans, which she serves at ranch events like round-ups and brandings, and her grandfather Harrold Poett’s mild green olives, which are made by soaking the olives in salt or lye, a method that is also recorded in other Californio cookbooks.

Like some of the cooks who came before her, Elizabeth plans to publish a collection of these recipes in a cookbook, so that her ancestors’ culinary traditions can be appreciated by cooks across the state and country. While her book will incorporate many of the contemporary California dishes that her family eats, recipes like her great-grandmother’s enchiladas and empanadas will stay the same as they have for generations. “I suppose I could make some changes and update them in some way,” Elizabeth told me recently, “but why would I? They’re so delicious just the way they are.”

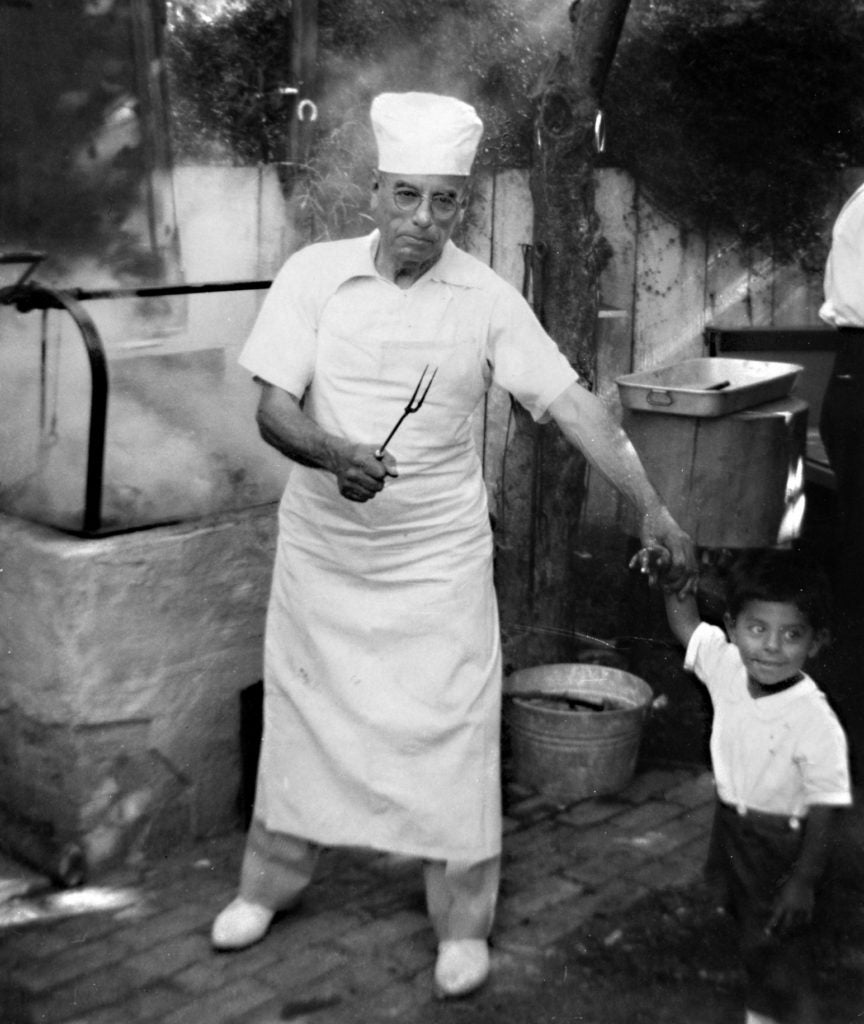

Photos courtesy of Jacqueline Higuera McMahan