A look inside the former critic’s vast collection of menus from across America.

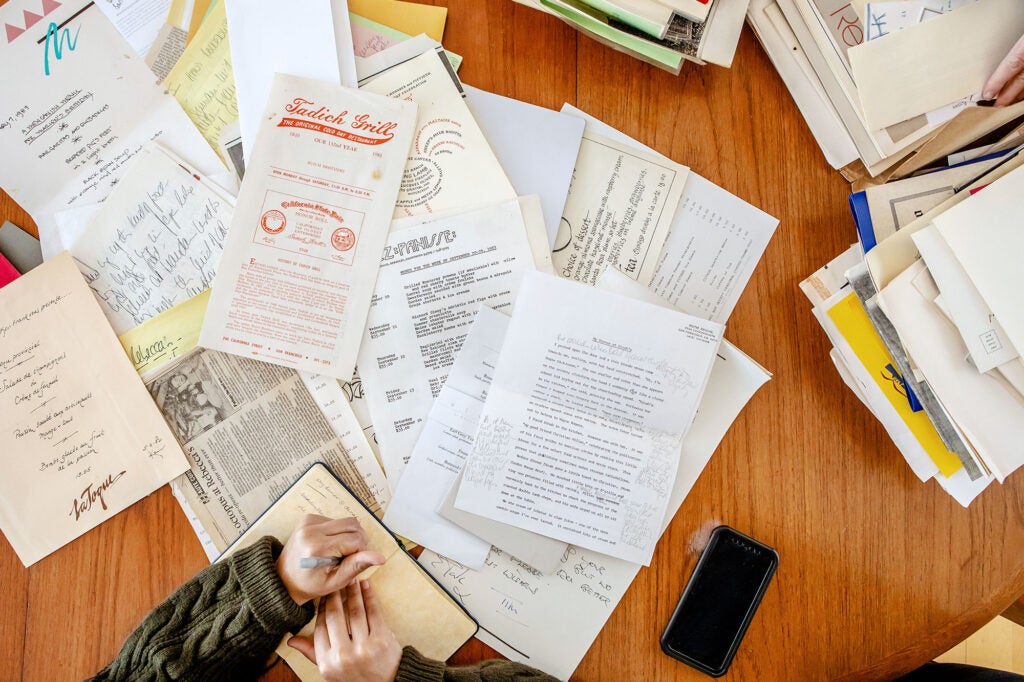

The history of the last few decades in American restaurants can be found in Ruth Reichl’s basement in Spencertown, New York, housed within dozens and dozens of beaten-up boxes—the same ones she used to move from Los Angeles to New York in 1993. This is where the menus live.

It started as a habit formed out of necessity—before a digital camera lived in everybody’s pocket by default, stealing menus was the only way to keep a record of a meal when she was a restaurant critic for New West magazine, the Los Angeles Times, and then the New York Times in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s.

But what began as a habit turned into a genuine curiosity about what menus say about their time. Every little detail, from the prices to the dish descriptions to the aesthetic choices, illuminates something about where we were as a society in that moment. What we valued back then. “I’ve always thought of menus as amazing artifacts,” Reichl says on a late-December morning, driving up the long, snow-filled driveway toward her home. “You watch trends come and go. You see ingredients come and go. You watch the impact of immigration law. You see the impact of certain restaurateurs.”

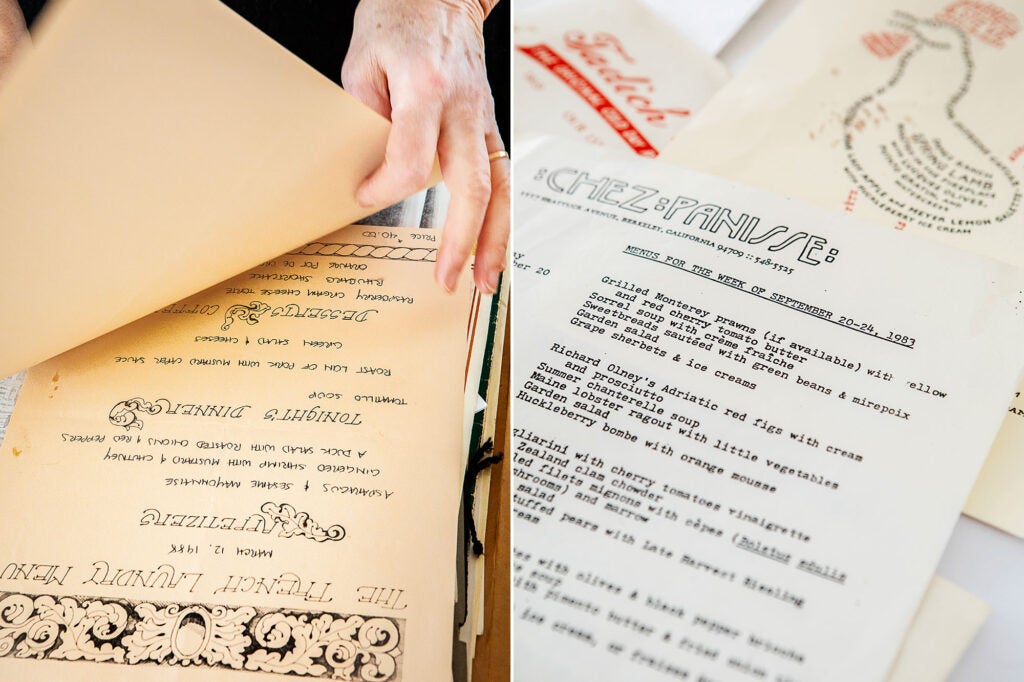

The menus vary in style and format—from an unadorned red pamphlet for an extravagant feast at New York’s Shun Lee to celebrate the Chinese restaurateur Cecilia Chiang in 2002, to a dainty handwritten lunch menu advertising Zanzibar duck with papaya for the French Laundry from the late ’80s. Often the menus have scribbles—notes Reichl penned as soon as she got home from meals to jog her memory. “Beautiful plate,” it says next to a crab soufflé with mangoes and lobster butter sauce from Röckenwagner in Los Angeles. “Balanced,” it says alongside a poached red snapper with potatoes, croutons, and saffron sauce, a few entrées down.

Reichl estimates that she has a few thousand menus sprawled across her home in upstate New York and her apartment in Manhattan. Most are from her days as a restaurant critic. Others are vintage menus she picked up at antique shops or special menus from restaurant events she has attended in recent years. “I am not a collector,” she insists. “I’m just a pack rat.” She has plans, eventually, to donate the whole collection to New York University, “but I don’t want to give them up yet.”

Reichl partially attributes her obsession with menus to her late father, Ernst Reichl, a renowned book designer. “He would design anything, even catalogs,” she recalls. “People would ask him, ‘Why do you waste your time doing a sewing manual?’ and he would say, ‘People look at it. It deserves to look good.’ You could say that about menus. They are a calling card for the restaurant.”

Recently, Reichl began posting a few old menus to her Instagram. So I asked if I could come and have a look at her collection. I made the trek a couple hours north of New York City, and Reichl picked me up at the train station and drove to her cozy, light-filled home, which is so idyllic it feels like a Nancy Meyers movie set. We dumped dozens of menus onto her dining room table, and as we sorted through them, munching on hunks of baguettes smeared with goat cheese and layered with duck prosciutto as the snow fell outside, Reichl took a trip down memory lane.

The French Laundry (1988), Bay Wolf (1970s), Greens (1979 or 1980), Chez Panisse (1983) — San Francisco, Oakland, and Berkeley

“It is interesting to me how similar these menus are in the way that they look, and—this was very unusual for the time—they are all prix fixe. At the French Laundry, before Thomas Keller took it over, it was owned by a family named the Schmitts. You can see how their food is kind of hard to characterize, at this time when so many restaurants were either French or Italian.

“With the Greens menu, the first thing I notice is $18 for a full meal. Wow. This was probably the first serious gourmet vegetarian restaurant that was seriously wonderful. Deborah Madison was doing amazing food. I am pretty sure this was one of my earlier reviews.

“Then, on the Chez Panisse menu, what I see here is that the weekday menus are more interesting than the weekend menus. Early in the week, you have grilled Monterey prawns, sorrel soup, sweetbreads. I mean, what a great menu. By the end of the week, you are having saddle of lamb—for people with less adventurous tastes.

At Bay Wolf, look at this. You are getting a full meal for $12.50. And this is the only one written in French, which is interesting. Writing a menu in French back then was a way to telegraph your bona fides. We are probably looking at ten years between all these menus. It was a great ten years in Bay Area food.”

Michael’s (1980) — Los Angeles

“I spent a year doing a piece on the opening of Michael’s. I have two menus here—one is from 1980, and entrées are $12, and the other is from 1982, when entrées jumped up to $20. That happened pretty fast. This restaurant, run by Michael McCarty, was one of the first consciously American restaurants. While Sally Schmitt of the French Laundry and Alice Waters [of Chez Panisse] were people who loved to cook and open restaurants, Michael’s was helmed by young, trained chefs. I wanted to do a piece on the opening of this restaurant because these chefs were all from America, using American products, and serving American wines. That was revolutionary enough to sell the idea of this story. I got paid $500 to do a story that took me a year.

This place had a really serious collection of contemporary art. Michael got Ralph Lauren to design the outfits the waiters wore. He hired chefs like Jonathan Waxman, Ken Frank, Mark Peel, Nancy Silverton. You can see on this menu that he is thinking really seriously about typeface, and there’s also art on the cover. Michael always had incredible taste. You can also see raspberry vinegar and goat cheese here—two ingredients that were very much of their time. But I would eat anything on this menu pretty happily today. It always bothers me, though, that for this American restaurant, the menu was written in French.”

Siam Cuisine (1984) — Berkeley

“This is a modest Thai restaurant in Berkeley, but probably the restaurant I went to the most often when I lived in the Bay Area. This menu was for my going-away party, when I was leaving to become the restaurant critic of the Los Angeles Times. I remember the event, but I don’t really remember the meal. This restaurant was my first introduction to this kind of food, where I discovered that I really loved chiles. The title of the menu is ‘The Last Hot Supper,’ though I don’t think anyone today would consider this food hot. When I first discovered this place, I remember thinking, Let me go eat this food as much as I possibly can.”

Citrus (1986 or 1987) — Los Angeles

“This chef, Michel Richard, was one of the few chefs I have met who really loved to cook. Michel was miserable when he wasn’t in the kitchen. You would go to Citrus and say, ‘Make me something.’ And he would come out with the most incredible food, always. There would always be—oh, look at this menu: oyster spinach flan, yum. Lasagna of escargots with fried parsley in a light garlic sauce. I want to eat everything. I remember, when I reviewed this place, walking in and being completely and utterly blown away by the food—very few L.A. chefs did that.”

Shun Lee (2002) — New York

“The food at Shun Lee is basically white people food. But this menu, created for the great restaurateur Cecilia Chiang, is one of the best Chinese meals I have had. There was a Panda Garden, which was this complete set piece with a panda made out of food. There was shark fin soup (this was before we knew we weren’t supposed to eat shark fin), and the fins were whole. There was XO sauce, which had yet to become a big deal in restaurants. I especially remember the eel because the chef [Man Sun Dau] brought in live eels and served them with fish lips. Eel and fish lips? You do not think of Shun Lee for that. Shun Lee is sweet and sour pork and egg rolls, and the idea that he had chefs in his kitchens who could do these things made me crazy.

It was like, if I really want great Chinese food in New York, I have to call up Michael Tong and say that Cecilia Chiang is coming? All that has changed now. You can get great Chinese food in New York. But 18 years ago, you had to go to Flushing, and you had to speak Cantonese or Mandarin. This meal was so delicious and exciting. Every single thing was gorgeous. I loved every last minute of it, and it also made me crazy.”

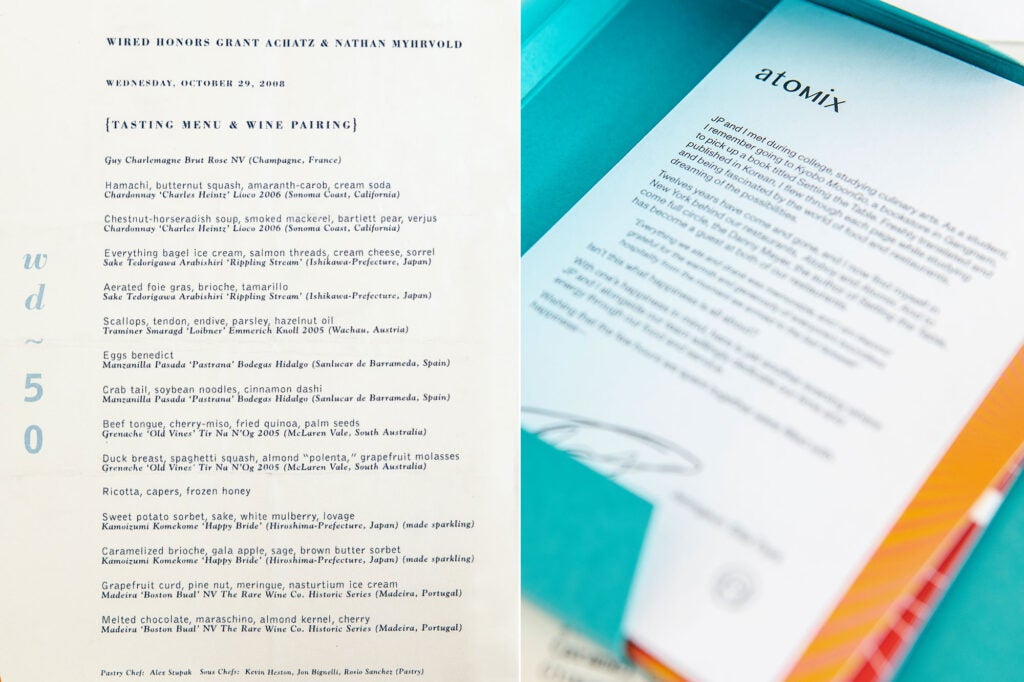

wd~50 (2008) — New York

“So the first thing I notice on this menu is that the pastry chef is Alex Stupak. And look who else is doing pastry—Rosio Sanchez. So many people came up through that kitchen. I have to admit, I was slow to understand what Wylie [Dufresne, chef-owner of the now-closed wd~50] was doing. I remember my first meal at wd~50: He did shrimp with cinnamon, which I still think is a terrible idea. But this meal was extraordinary and surprising in every way. Wylie has always cooked outside of the lines, but at this dinner, he was cooking for Grant Achatz and Nathan Myhrvold. They are hard to impress. I remember seeing tendon on this menu and thinking it was going to be a trendy ingredient. And it was! I wish I could remember the meal. I can’t. I just remember being truly blown away by it.”

Atomix (2018) — New York

“The ambitions for this restaurant are for it to be a real learning experience, and you see that in the menu. I have been sitting here saying that I don’t remember these meals. Here, I can look at these individual cards with descriptions of each dish and go, ‘Oh yeah, I remember this.’ They really want you to know about their food. People in America have such a pathetic idea of Korean cuisine, and this menu invites you to think about what you have eaten and how elegant it is. You can take these cards home and relive the experience. [Owners Ellia and Junghyun Park] are thinking about menus as something that lasts. Most people think of menus as something you leave behind at the restaurant, and when the restaurant closes, they will vanish forever. Atomix is thinking, We don’t know what is going to happen with our restaurant down the road, so how do we leave a lasting record of what we have done? It is a very thoughtful idea of what a menu can be.”