For many Asian immigrants, potato chips sprinkled over rice is a reminder of how they circumvented assimilation.

The choices were dazzling: barbecue, cheddar cheese, jalapeño—and that was just the first shelf. My 16-year-old brother and I, newly 10 years old, walked the chips aisle, back and forth, while our amma, still jetlagged, perused the “ethnic foods” section for basmati rice. We were used to the farmers markets of South India—to eyeing and squeezing and negotiating prices of baby gourds and okra. We were not so used to the luxurious expanse of the grocery store’s chip aisle in Calgary.

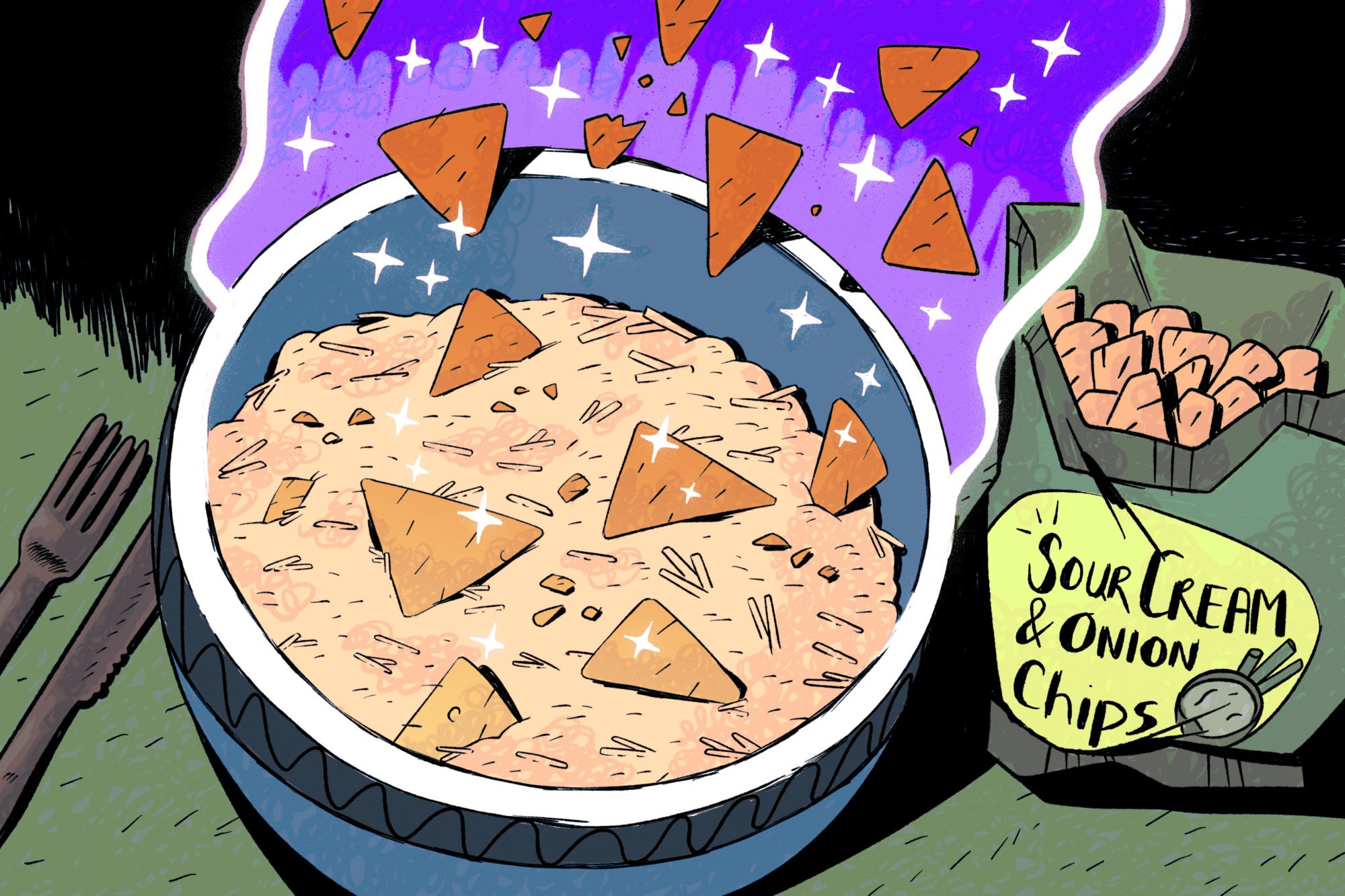

It was already dark when we returned to the cramped two-bedroom apartment we lived in for our first months in Canada. Amma prepared the rice in the steel pressure cooker she’d shipped from India. But unable to find tamarind paste or black mustard seeds at Safeway, she couldn’t make the potato curry she’d planned. In its place, a new family tradition was born: white rice sprinkled with potato chips.

There were salt ‘n vinegar chips for my brother, and sour cream and onion for me. Of course, we’d had chips before—thick sweet plantain ones and homemade potato chips spiced with cayenne. But I couldn’t have dreamed up the garlicky kick, the powdery tanginess, the paper-thin crispiness of sour cream and onion. I licked a chip, one side and then the other, sucking up every bit of flavor, before popping it in my mouth. Sprinkling the chips on rice created a perfect fusion of crunch and tender fluffiness, of bold taste couched in the blandness of white rice.

Maybe to soften the blow of all we’d left behind in our home country, or just because we begged her incessantly, Amma started giving us handfuls of chips with both dinner and the lunches she packed: rice and dal, aloo gobi (potato stir-fry) or bhindi (okra curry), plus a ziplock bag of chips, all stuffed into my backpack. Inevitably, the chips got crushed, and I liked them that way, too.

One day in fifth grade, watching me carefully top my rice and curry with disintegrated chips—sour cream and cheddar this time—Angela, a Chinese girl, sat next to me. From a paper bag, she withdrew a container of white rice and veggies, and a bag of barbecue chips. Silently, she took out a handful of chips, sprinkling them on top of the main dish. We took a bite of each other’s lunches. Hers was utterly different: the chips sweet-hot, the veggies unfamiliar—mushrooms and chewy greens cooked in a garlicky sauce—and yet it was the same basic configuration. We smiled at each other, in newness and in recognition.

This is how we became friends: eating together every day, always swapping bites of each other’s meals. It wasn’t long before other Asian kids—from Pakistan, China, and the Philippines—started joining us, bringing their own rice-and-chip combinations. I remember the spiciness of biryani perfectly offset by plain salted potato chips, creamy ranch chips mixed into fried rice, and jasmine rice topped with jalapeño chips. For us first- and second-generation Asian immigrants, it was the best of Asia and North America combined. And for me, it was the first time I didn’t feel out of place in this new continent.

Jeff Mo, a high school friend who prefers his rice with ketchup chips, left mainland China with his parents when he was three. “One day I just decided my rice was boring and flavorless,” Jeff recalls. “And perhaps my mom also said I couldn’t have chips until I finished my rice, and this was my in-between solution.”

In a culture that recognizes only certain formulas of cuisine, rice and chips remains a sort of secret code, especially for immigrants: an inside joke that’s not a joke.

As Soleil Ho writes for TASTE, “in-between” foods like this, fusing traditional cuisines with ingredients available in their new surroundings, are cherished by many immigrants. They can symbolize transformation but also the reluctance to transform entirely—to divest culinary heritage for the dubious prize of blending in. “Assimilation foods” like these can unite people from other continents here on this one, around unpretentious, entirely accessible ingredients. For me, rice and chips has also been an unexpected pathway to community.

A friend I met during college, Aileen Amigo Macaraeg, recognized the ritual from her own childhood. “My mom ate rice and chips as a meal after arriving in Canada from the Philippines. No veggies, no extras,” she says. “Now I give this to my kids. They love it, and for me, it’s a nostalgic moment that reminds me of my childhood.”

At its most basic, the carbs-on-carbs combination is admittedly lowbrow, but it doesn’t have to be: I’ve garnished puliyogare, a tamarind-tinged South Indian rice dish, with sour cream and onion chips to serve to my mother and friends, both times to great acclaim. San Diego chef Angelo Sosa likes to top his turkey fried rice with chips.

In a culture that recognizes only certain formulas of cuisine—fast food or farm-to-table, “ethnic” or American—rice and chips remains a sort of secret code, especially for immigrants: an inside joke that’s not a joke. It brings together people and their multiplicity of selves, each one rooted in a different place. For many of us, it might be as close as we can get to that ephemeral concept of home.