Australia? Southern California? No, avocado toast is from someplace else. Of course it is.

I wasn’t looking to dredge up the history of avocado toast. I did not grow up eating the buttery fruit mashed onto crisped bread. I was born and raised in Massachusetts, where approximately no one has an avocado tree in their backyard. And while I eat a lot of avocados, I rarely eat them with toast. I just wanted to know how to pick out a good one, one that is soft and creamy without any brown spots. But when I started asking chefs and cookbook authors about that, I found that there was history left out of the conversation about this beloved, and hated, dish.

The debate over who invented avocado toast was kicked up about a year ago. Besha Rodell, a former restaurant critic for LA Weekly and a native of Melbourne, Australia, made a passing reference to it in an ode to Melbourne’s eating culture for Eater. “Avocado toast is a 100 percent Australian invention, insofar as any one ingredient on a piece of bread can be,” she wrote. These words were tucked in a parenthetical on America’s newfound obsession; its provenance was a fact so 100 percent that it didn’t even require its own sentence. Wittingly or unwittingly, Rodell had thrown down a gauntlet, and it was only a matter of time before someone took it up.

About 8,000 miles away, in another sunny, coastal city—where similarly lithe and tanned creatures sip green juices in between Kundalini yoga and shopping for $900 muumuus decorated with tribal prints—California writer John Birdsall took up the historical case of avocado toast for Bon Appétit. While admitting that there’s “little doubt that avo toast—the Instagram kind—can trace its existence to [Australia],” he proclaimed that Los Angeles is “the place where avocado toast was actually born.”

In old newspaper archives, Birdsall found a recipe dating back to 1920 in San Gabriel’s Covina Argus, from Martin Fesler, who instructed readers to mash avocado with a fork and spread it on “a small square of hot toast.” Here were the Dead Sea Scrolls of millennial brunch. If Rodell’s avocado toast was the fetishized kind popularized by stylish restaurants, Birdsall winnowed it down to its most elemental form: avocado plus toast. To varying degrees, the modern avocado toast came out of both California and Australia. But the elemental Ur-avocado toast wasn’t born in either place. Of course it wasn’t.

For the Instagrammable avocado toast served at fashionable all-day cafés, Bills in Sydney is, indeed, where it got its start. In 1993, Bill Granger was looking to open a restaurant. Only 22 years old and with no formal chef training, he found that landlords were, not surprisingly, hesitant to rent to him. So he took the only lease he could get: one that stipulated that the restaurant could be open only from 7:30 a.m. to 4 p.m., Monday through Saturday.

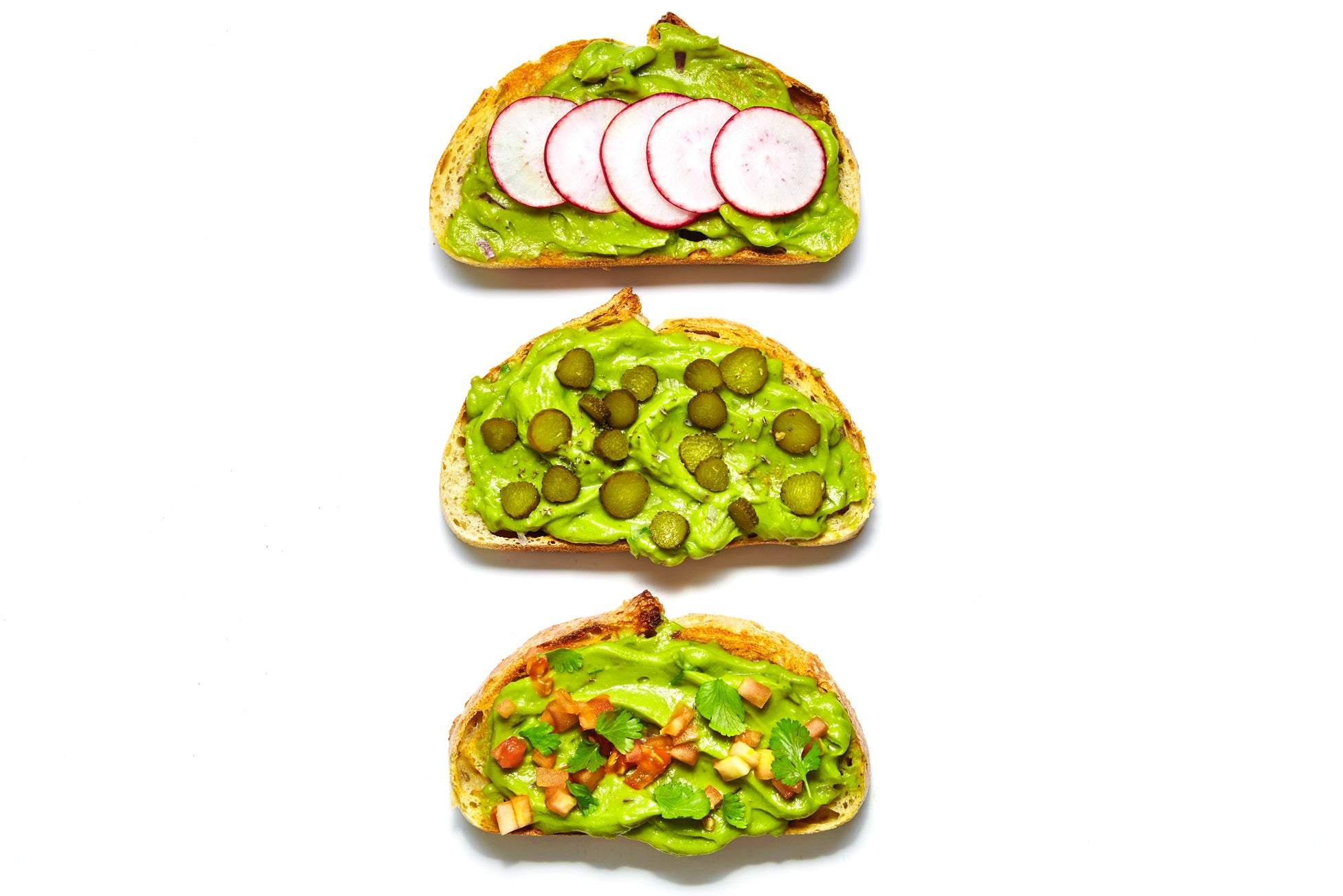

“I had to make breakfast work,” Granger recalls, over the phone, of his fledgling restaurant’s odd hours. At that time, only Italian cafés and hotels were open in the morning, so he took his cues from elsewhere. “I was inspired by the States, the diner that you could go to all day,” he says. Because Granger wasn’t a trained chef, he focused on home-cooked food, but it wasn’t the greasy-spoon fare of his American muse. “In Sydney, your body is on show,” he says. In a place where the climate is warm, the clothes are skimpy, and athleticism abounds, there’s a natural motivation to eat healthfully. One of Granger’s first dishes was avocado quarters laid on sourdough bread and dressed with just lime juice, olive oil, and cilantro leaves. The avocado toast was a simple, wholesome food that an inexperienced young cook could turn out to a body-conscious public.

Seventeen years after Granger opened Bills, a young, relatively unknown American chef named Jessica Koslow showed up in Melbourne to soak in Australia’s modern café culture. After working in Fitzroy’s Dench Bakers, and a detour in Atlanta, Koslow returned to her birthplace, Los Angeles. And in 2011, she opened Sqirl, a daytime restaurant in the Australian model, with the operating hours of 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. and her own version of avocado toast topped with a worldly assortment betraying her professional cooking background: garlic cream, pickled-carrot curls, sumac, and sesame seeds. This would be a pivotal moment. Putting serious cooking technique behind trendy wellness food, Sqirl set the stage for a new kind of American restaurant.

Here were the Dead Sea Scrolls of millennial brunch. If Rodell’s avocado toast was the fetishized kind popularized by stylish restaurants, Birdsall winnowed it down to its most elemental form: avocado plus toast.

Granger may have been the first Australian to put avocado toast on a menu, but he was no means the first Australian to put the two things together. Surprisingly, the arrival of the avocado tree in Australia around 1853 actually predates its arrival to California by a few years. While avocado trees were already flourishing in Hawaii and Florida, dating back to 1833, they didn’t make it to California until 1856. An agricultural dispatch from the British publication The Colonies and India in 1891 includes, perhaps, one of the earliest accounts of bread and avocado, then called “alligator pear,” from Australia’s Brisbane Botanic Gardens. A Mr. Turner of the Gardens kept Sir W.W. Cairns, the governor of Queensland from 1875 to 1877, well supplied with the “very fine fruit.” Alligator pears weren’t popular in Australia at the time, but the “Governor told Mr. Turner he was very fond of the fruit for breakfast, and he used to eat it spread on bread, with pepper and salt to give it some zest.”

The account doesn’t specify whether or not the governor toasted his bread, an insignificant detail unless you’re a food writer looking into the provenance of a thing-on-toasted-bread in 2018. It’s entirely possible either way. Crisping the surface of the bread, making it easier to spread the buttery fruit on it, is as natural as the impulse to pair the two foods. But I’d even venture that the toasting part of avocado toast is not its defining feature, inasmuch as you’d probably still call it “avocado toast” and not “avocado bread” if the starchy thing in question were unscorched.

In the 19th century, it wasn’t just the Australians who had an affinity for the pairing. Avocados were so well known among the British that they were called “midshipman’s butter” or “military subaltern’s butter.” Even then, avocado toast was a dish for the fashionable. An 1843 dispatch from Tortola, the largest of the British Virgin Islands, in the Manchester Guardian recalls that the breakfasts for “the sharp-set” included “the fine avocado pear called among the military’s subaltern butter,” which they ate on French rolls or the garlicky “common island loaf.” As long as Westerners have come into contact with this produce “butter,” they’ve been spreading it on bread. But it’s certainly not a practice exclusive to Westerners—and it goes back much earlier than the 19th century.

“We’ve been eating bread with avocados all our lives,” says Cuban-born chef Maricel Presilla, the author of Gran Cocina Latina: The Food of Latin America. “If there’s an avocado ripening and a nice loaf of Cuban bread, we don’t think about it, we just do it. It’s so common, it’s a non sequitur.”

Its commonness may be the reason you won’t find a recipe for avocado toast in any of Presilla’s cookbooks. The written instructions for how to prepare it are only necessary for those whose own culture is not intertwined with the odd-looking fruit, once known as ahuacate before the California Avocado Association renamed it “avocado” in 1915. In an 1882 dispatch from Jalisco in The Times-Democrat of New Orleans, a reporter finds that “the finest fruit in Mexico is a vegetable and that vegetable is the ahuacate…there are scores of ways of preparing the ahuacate. Eaten raw, with bread and salt, one soon learns to like them.” While this dispatch does not predate the one from Tortola, I would hope that reasonable minds could agree that, in all likelihood, the first spreading of avocado on toast most likely occurred not in any newly adopted home, but the birthplace of avocado itself: Mexico.

“The first mentions of avocado date back 10,000 years to Puebla,” says Rico Torres, co-chef of Mixtli in San Antonio, Texas. If I’ve calculated it correctly, that’s many thousands of years before a tree arrived in either California or Australia. “Guacamole was the most common way they used it,” he says. Guacamole, that green sauce that has since become known among millennials for its add-on cost, was a foundational Aztec food, so much so that early Spanish settlers called avocado “mantequilla de pobre” or “butter of the poor.” Bread arrived in Mexico with those Spanish settlers in the 1500s, and it wouldn’t be a stretch to think that people started toasting and spreading as soon as the two foods came together.

Today’s seemingly over-the-top obsession with Instagramming the creamy green fruit carefully arranged on Technicolor grain bowls pales in comparison to the Aztecs’ reverence for the avocado. “They thought of it like a fertility fruit,” says Torres, noting that the word “ahuacate” is derived from the Aztec word for testicle, “ahuáctl,” perhaps a reference to how the fruit grows in pairs on trees. “There were stories of young women not being allowed to go outside while it was being harvested.”

Before the Spanish showed up, Aztecs were making their own version of the dish. “The original avocado toast is the avocado tortilla,” Torres says. Bread may be used in tortas and street sandwiches, but in Mexico, the craft of the tortilla is still unmatched. “I think the toast got popular since good tortillas are harder to get in other countries,” says Mexico’s superstar chef Enrique Olvera. “In Mexico, there’s a saying that goes: ‘To the lack of tortillas, bread.’”

Somewhat trepidatious about the charged debates over cultural appropriation, I approached my conversations about the origins of avocado toast gingerly. But Torres was nonplussed. “It just seems obvious when you see those two things on the counter,” he says, almost perplexed about why anyone would be researching it. He wasn’t alone, either.

“It’s not that big of a deal,” says Zarela Martinez, a former New York City restaurateur and author of The Food and Life of Oaxaca. “Toasted bread is perfect for an appetizer. I think I saw it served in Mexico,” she adds, slightly bored, but graciously trying to humor me before trailing off. “But I don’t really remember.” I started to feel as though I were asking about how one would position cheese onto a cracker and who had come up with the novel form.

While Presilla made sure to press on me the fact that the avocado toast is “very, very old,” the Mexican food experts I spoke to were disinterested in contesting the ownership of avocado toast, almost as if claiming it were beneath the dignity of their beautifully complex and ancient cuisine. “In Mexico, we use avocado with everything: bread, tortillas, rice, beans, steak, chicken, soups, salads, desserts,” says Olvera, who has a guacamole toast on the menu of his New York restaurant Atla. “It’s a side dish on most tables, like salsa. We just don’t have specific names for doing it. The avocado toast is more of a trend. And in that sense, I don’t think it was invented in Mexico. It’s too common.” Who needs to quibble over putting a vegetable on bread when you have mole?

In his 1999 cookbook, Sydney Food, Granger only included an avocado toast recipe to fill out empty page space. “I thought it was embarrassing at the time,” he says. Needless to say, the dish has taken on a life of its own since then. “It’s become a cultural signifier,” Granger notes. This year, Australia is on track to produce 70,000 tons of avocados, but to meet domestic demand it has to import another 20,000 tons from New Zealand. That’s according to Granger’s produce supplier, Vincent Tesoriero of Verdi Verdura.

Even in Tesoriero’s lifetime, its accessibility has changed drastically. Before Australian farmers could grow the fruit year-round, imported avocados could be as much as $7 in the winter. That changed in the 1980s, when the Hass came to Australia from California. Now the world’s most dominant variety, the Hass is rather young in the history of the avocado. In 1926, California postman Rudolph Hass, who bought the cultivar from local grower A.R. Rideout, planted a seedling of the fruit in his backyard; it quickly became popular among California growers. The Hass tree had a higher yield and longer growing season, and its fruit also shipped well, thanks to a thicker skin. It was perfectly engineered for commercial distribution, driving the prices of avocados down in Australia just before Granger opened his seminal café. The Hass was also extra oily and creamy, making it the perfect foil to toast.

The written instructions for how to prepare it are only necessary for those whose own culture is not intertwined with the odd-looking fruit.

In some ways, avocado toast as cultural currency is the result of this exchange between California and Australia. In 2010, the same year Koslow was in Melbourne absorbing the appeal of cheffed-up avocado toast, Stanford graduates Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger launched Instagram in San Francisco, rapidly reaching 10 million users within the first year. It was California that modernized avocado production and birthed performative wellness in the form of shared staged brunch photos, and Australia that introduced this new breed of all-day café with health food worthy of serious culinary consideration.

Now, this still doesn’t explain why—really, why—a food so common became a social media phenomenon. If every movement is a reaction to the one before it, avocado toast is easily pinned to the modern Western wellness movement, which is, no doubt, a reaction to the processed foods that came to dominate and define the American way of eating in the 20th century. Today, about two thirds of Americans are overweight or obese, and every country to which America has exported its packaged foods has also experienced negative health outcomes. Australia is no different, and Mexico’s newly rocketing obesity rate was recently tied to NAFTA and its attendant influx of McDonald’s and Dominos, supplanting farm-grown produce, stews, beans, and tortillas.

Beauty has often been tied to the appearance of wealth or, to be more accurate, the appearance of not being poor. When the poor were lean and tan from working in the fields, chubbiness and fair skin were in vogue, an indication of leisure and wealth, and when the poor became fattened by processed foods and pale from factory work, thin and tan became the rage. While the Western diet wreaks havoc around the world, displacing ancient wellness practices, indigenous foods like turmeric, quinoa, goji berries, and chia seeds have been plucked from their original context and cropped into an Instagram frame alongside fair-skinned bikini beauties with enough leisure time to painstakingly document their lunch. We don’t tend to portray our fashionable wellness foods with darker, rounder bodies in faraway places, even if those faraway places are much closer than Sydney. But if great chefs and food historians of Mexico aren’t mad about the reframing of avocado toast, then I suppose I have no place to be, either. Although I might suggest that if we all must chew both on the food itself and its cultural significance, it’s worth examining its original form.

So consider the avocado tortilla. Like its bread-based descendent, it is rich in panthenic acid, folate, vitamin K, and good, delicious fats. Better yet, traditional tortillas are made with nixtamalized corn, and the blue ones, in particular, boast extra nutrients. They are gluten free, after all, and with less starch and more protein, they have a low glycemic index, a measurement of a food’s impact on blood sugar that is associated with better health. Besides, those blue heirloom corn tortillas? They really pop on Instagram.