Then she taught their American kids to cook too. Meet the remarkable Fu Pei-mei.

In one of my favorite old clips of Fu Pei-mei, it’s sometime in the 1980s, and the mild-mannered cooking instructor is demonstrating her technique for making “squirrel-fried” fish, one of her signature dishes. With a few well-placed strokes of a knife, Fu debones a whole yellow croaker, scores its flesh, and then fries the fish in a wok until the meat unfurls and puffs out like a squirrel’s bushy tail. On the bare-bones set of her long-running series, Fu Pei-mei Time, she wears a mom apron and sports a tidy Asian-mom perm. More than any other television chef I’ve seen, she looks like she could be my mom—if my mom gripped a giant meat cleaver at all times.

Before Martin Yan wisecracked his way into the hearts of PBS viewers in the early ’80s, and long before Ming Tsai spread the gospel of East Meets West cooking on the Food Network, there was Fu Pei-mei. Fifteen years after her death in 2004, Fu remains the most famous culinary figure Taiwan has ever produced. As the host of the country’s first cooking show, she was on television for about 40 years—nearly 2,000 episodes instructing on more than 4,000 Chinese dishes, and she never wore the same apron twice, it seemed, in all that time.

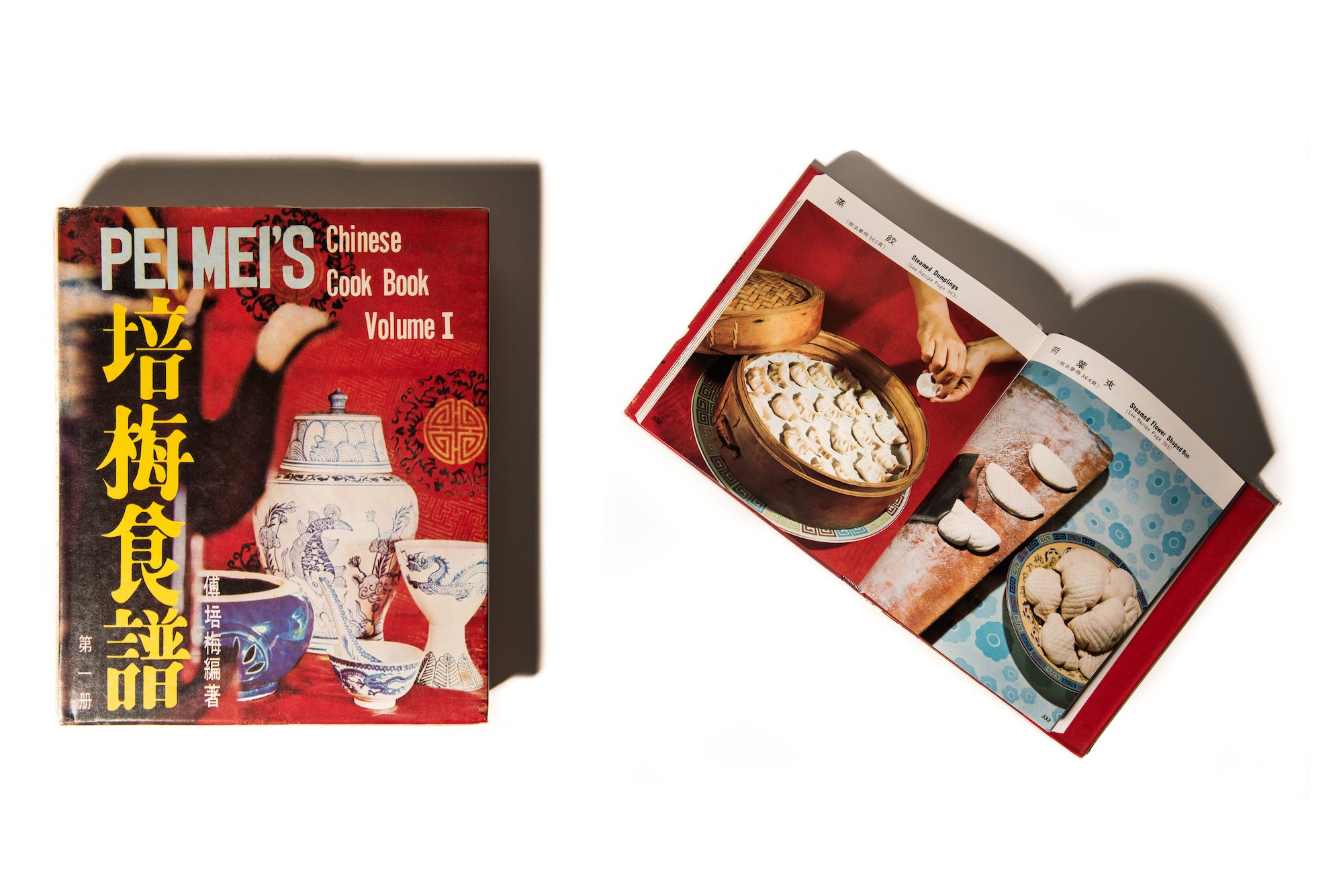

The show aired in Mandarin, but Fu also spoke English, Japanese, and Hokkien, allowing her to spend the latter part of her career traveling the world as a kind of culinary ambassador. She had a Chinese cooking show in Japan for several years. And if you talk to anyone who came of age in Taiwan in the last 20 or 30 years, chances are that they—or their parents—have a copy of Pei-Mei’s Chinese Cook Book stashed away somewhere. (The book’s first volume, now out of print, sold 500,000 copies.) The New York Times restaurant critic Raymond Sokolov called her “the Julia Child of Chinese cooking” in a 1971 write-up that highlighted two of Fu’s recipes for cold chicken salad—both of them “traditional” and “easy to prepare,” according to the Times.

The Julia Child comparison is made in every English-language article about Fu. But Michelle King, a historian at the University of North Carolina who is writing a book about Fu (tentatively titled The Pei-Mei Project: History, Gender, and Memory Through the Pages of a Chinese Cookbook), says the real sign of how large she looms in Taiwan is this: To this day, if the Taiwanese media wants to establish a person’s bona fides as an authority on a particular national cuisine, they inevitably describe him or her as, say, the Fu Pei-mei of British cooking (in reference to The Great British Bake Off’s Mary Berry), or the Fu Pei-mei of America (Child herself, naturally). “That is how all other cooks are described in Taiwan,” King says.

In my Chinese-Taiwanese family, Fu Pei-mei was a household name. Her cookbooks—three well-worn volumes, with recipes in the original Chinese on the left-hand page and English translations on the right—were the only ones I ever saw my mother use when I was growing up in the New Jersey suburbs. After college, when I wanted to learn how to pull off a basic chicken stir-fry, or to deep-fry shrimp balls for a dim sum–themed dinner party, those were the books she lent me.

When I visited Taipei as a kid, anytime my grandmother and my aunts didn’t feel like cooking, someone would run out to the 7-Eleven to grab a few packages of the instant noodles we all called “Fu Pei-mei’s beef noodles.” These weren’t actually branded under her name, but it was common knowledge that Fu had consulted with the Uni-President food conglomerate on the recipe during the early ’80s; for years, there was a picture of her face on the packaging. Each pack came with a plastic pouch filled with luxurious, chile-tinged congealed beef fat and another filled, miraculously, with chunks of shelf-stable meat. It’s one of the tastes I most associate with my childhood.

My mother even took one of Fu’s cooking classes in 1978. She was 24, newly married, pregnant (with me), an inexperienced cook—too shy to ask any direct questions of the celebrity chef. The lessons took place in a small demonstration kitchen set up with desks for the all-female class roster. Before Fu started her cooking school, there weren’t any formal ways in Taiwan for young women like my mother to learn how to cook. The old model, King explains, was the restaurant apprenticeship system, which generally consisted of men teaching men.

What my mom remembers most is how clear and thorough Fu’s instructions were: This is how to pick the cut you want to use for the Cantonese-style roast pork. This is when you brush the marinade on so it won’t burn. This is why you slice the meat against the grain. “She was a good teacher,” my mother tells me. “She made you feel like there wasn’t anything so hard about it.”

Fu was born in 1931 to a wealthy family in the city of Dalian in northeastern China—land of exquisite dumplings—during the period of Japanese occupation. In 1949, when the Communists won the Chinese Civil War, Fu’s family—along with some 2 million Nationalist soldiers and other displaced mainlanders—resettled in Taiwan. She married at 20 and had three children within five years.

The somewhat unglamorous origin story of how Fu Pei-mei became one of the world’s great authorities on Chinese cooking came down to this: Her husband complained about her cooking. Fu often told the story of how he would invite his friends over to their Taipei home to play mahjong, and afterward he would give her a hard time about the terrible food she’d served their guests.

Fu spent two years and all of the money from her dowry, hiring chefs at restaurants all over Taipei to teach her how to cook their most prized dishes, and then doggedly recreated each one again and again until she had mastered it. (“We ate her experiments,” says Fu’s eldest daughter, Cheng An-chi, who later became an accomplished television chef and cookbook author in her own right.)

By the time she was done, she was able to cook restaurant-quality dishes from Shanghai, Sichuan, Hunan, and throughout the country. She could serve her husband’s mahjong buddies the cuisines of their own home provinces. By the late ’50s, she had gained a reputation for being such a good cook that she started giving cooking lessons, just in a tent in her backyard in the beginning. By 1962, Taiwan Television had put her on the air.

When Fu published the first volume of Pei-Mei’s Chinese Cook Book in 1969, it extended her reach even beyond Taiwan, in large part because she wrote it as a bilingual text, translating the recipes into English herself. For a long time, the three volumes in that series were perhaps the only authoritative sources for regional Chinese recipes that were available in English. In many first-generation immigrant families, the books were artifacts of our parents’ lives in Taiwan that were already packaged in a format that was accessible to us. No further translation was necessary.

Carolyn Phillips, a food writer and Chinese cookbook author who lived in Taiwan during the late ’70s and early ’80s, recalls that the books—with their color photographs and handy numbered diagrams—were so much more user-friendly than the dense, tiny-fonted Chinese-language cookbooks that ruled the day. They were also some of the first mainstream cookbooks to clearly articulate the regionality of Chinese cuisine—the first volume, in particular, was organized that way, divided into chapters on eastern, southern, western, and northern China, respectively. Phillips explains that prior to encountering Fu’s work, she had always thought about Chinese food as a monolith. “[Fu] was the first one to give me a hint that there was more to the foods of China than I had been aware of up to that point,” she says. “I began to realize, ‘Oh, China is really huge. Each part of China has its way of cooking.’”

For viewers of her television program, the regionality of Fu’s approach was a big part of the appeal. At that particular moment in Taiwan’s history, there was this huge influx of mainland Chinese transplants who had been living, for upwards of ten or twenty years now, on an island hundreds of miles away from the city or village where they grew up, with no hope of return.

For these displaced mainlanders, King explains, Fu’s show tapped into a sense of nostalgia for their home cuisines—but even native-born Taiwanese felt curious about the home cuisines of their new neighbors, who had come from so many different parts of China. Because so many of China’s great chefs had moved to Taiwan as part of the mass migration in 1949, this was the one place in the whole world where you could experience all of the astonishing diversity of Chinese food gathered together on one small island.

Before Martin Yan wisecracked his way into the hearts of PBS viewers in the early ’80s, and long before Ming Tsai spread the gospel of East Meets West cooking on the Food Network, there was Fu Pei-mei.

When you watch old clips of Fu Pei-mei Time today, what’s striking is how little Fu has in the way of what we, by today’s food television standards, might view as showmanship or natural charisma. She doesn’t tell jokes. She doesn’t share personal anecdotes. Everything out of her mouth is a nugget of plainspoken practical cooking advice. “Please remember to hold the eggs up very high,” she says in one episode, drizzling eggs onto a batch of hot-and-sour soup. “The higher up, the more delicately it’ll come down.” There were no wasted words or wasted movements.

Today, Fu Pei-mei’s name has faded a bit. Taiwan, like the United States, has no shortage of newer, flashier celebrity chefs. Still, by the time Fu died of liver cancer in 2004—the same year Julia Child died—her legacy was secure. She had helped tens of thousands of tentative home cooks like my mother build confidence in their own ability to prepare a delicious Chinese meal. She had done as much as anyone in the world to teach people—even Chinese people themselves—about the regionality of Chinese cuisine.

And for some of her most devoted fans, she meant even more than that. In the unapologetically melodramatic miniseries based on Fu’s life that aired in Taiwan in 2017 (now streamable on Netflix under its English title, What She Put on the Table), there’s a scene in which Fu prepares a plate of candied sweet potatoes for a man who has been terribly homesick for the foods he used to eat in his home province. He takes one bite and bursts into tears. “It’s good!” he sobs. “It’s so good! It tastes just like my mother’s.”

Fu’s eldest daughter, Cheng, says that particular scene was fictional. But the sentiment was rooted in reality. Eventually, Cheng recalls, Fu was famous enough that she was recognized everywhere she went: “We would go to the market, and people would see her and say, ‘You’re so amazing. You let us taste the flavors of home once again.’”

Inline book photography by Alexa Bendek