The fruit’s peak season offers a lesson in its rhythms, tastes, and varieties.

My father, like most people I know, measures his seasons by the fruit available in the market. He knows early winters by the tart, red apples that would come down from the mountains of Kinnaur in Himachal Pradesh. He recognizes spring when boxes of green Anab-e-Shahi grapes, all the way from Hyderabad, would appear in the local bazaar in his neighborhood of Mayur Vihar in East Delhi. “Garmi aa gayi, lagta hai,” he announced to me in Hindi three months ago in May, as he entered the house with a cloth bag slung over his shoulder. He had with him two round Dussehri mangoes, the first fruits of the season, not as sweet with the drippings of midsummer, and he suggested—showing them to me like collected evidence—“It looks like summer has arrived.”

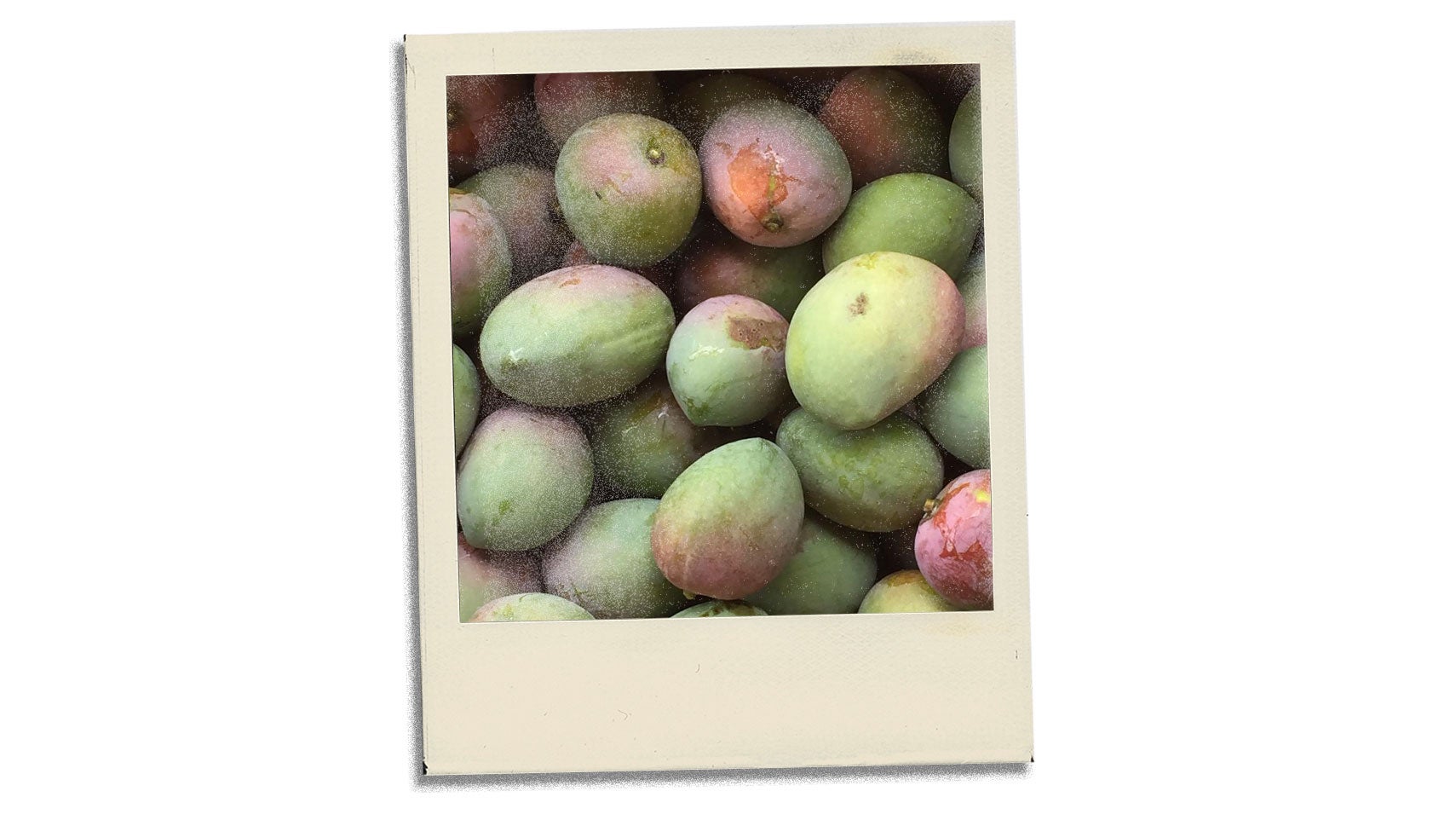

When summer began, I realized that I hadn’t been in Delhi for a stretch of mango season for many years. And now that I was locked in, my annual escapes from my city on permanent hold, like my father, I began to measure the season’s proceeds with the mangoes that would enter our home. Through the five months of lockdown, mangoes have been a solace—sweet Chaunsas the size of my fist, whose heads my cousins puncture whole and eat in one slurp; robust, green, Langras, with hard, bitter skins and sugary cores. My mother, who is South-Indian, defiantly waits for the ones she knows will be sent by her sisters in Bangalore: shining, golden Kesaris to eat slowly through their golden flesh, a bag of Totapuris—raw, pointy fruits that she cuts and sprinkles with salt, chile powder, and sesame oil.

I puzzled over the way mangoes are treated in the West, such as in videos for how to cut them best, with disclaimers “not to be afraid.” To categorize and rank the fruit into sentimental superlatives is confusing.

As I ate through the summer, I remembered that my favorite mangoes were the ones I cannot identify, which my father calls “bageechay kay aam” or “mangoes from the garden,” signifying their anonymity; these are mangoes that mysteriously fall from a tree into a lucky person’s lap. Recently, I ate a pile while traveling through scorching Uttar Pradesh on the way to Kanpur, the car’s driver and I throwing our seeds out as he raced on the highway, laughing at the manic rush of it all. In July, relatives sent a basket from Amroha, a small town in the same region—plump with stories my uncle Gulzar Naqvi used to tell me about his ancestral home.

I puzzled over the way mangoes are treated in the West, such as in videos for how to cut them best, with disclaimers “not to be afraid.” To categorize and rank the fruit into sentimental superlatives is confusing. There are hundreds, maybe even thousands, of mangoes all over South Asia; each one belongs to a village, a family, and a memory. Who cares which mangoes are sweetest? And who dares decode this thing that holds such manipulative pleasure that it turns affable siblings into warring parties, chasing after one another about who gets the guthli—the meaty bits around the shell?

Now that summer is at its end, mango season is, too. In typical Delhi irony—the harsher the weather, the sweeter the fruit; with rains come softened skies and relief, but also remorse as the mango departs. Yesterday, I walked to the cart near my house to hassle Iqbal, the young man who sells me my mangoes, complaining to him about my father’s latest purchases, asking banal questions whose answers I already knew.

“Are these fresh? Is this one sweet?’ I whined. “Pehlay pyaar say meetha, aur pehlay badlay se bhi,” Iqbal said, grinning. “Sweeter than first loves and first revenge.” As Iqbal sorted the fruits, a band of uncles patted his back and glared at me—who was I to ask questions of the last flush of the beloved fruit that would soon disappear from our lives? After the uncles left, I told Iqbal my first love was not sweet; it was bitter, in fact. “Nothing is sweet at its core, except these,” he said, handing me two large Langra mangoes wrapped in newspaper so they could ripen with ease. “That is why we wait for them without question, every year.”