In the 1980s and ’90s, a wave of unapologetically queer cookbooks beat the odds and made it to print.

When Amy Scholder looks back on her cross-country move almost three decades ago, she remembers two catalysts: her growing career, and the AIDS epidemic. The year was 1996, and Scholder was a rising star in San Francisco’s publishing world, where she worked at the legendary beatnik imprint City Lights as a literary editor. She earned a reputation for putting together anthologies and single-volume books by people of color and folks from marginalized communities—authors, she says, who she felt weren’t adequately represented in mainstream book publishing. But in the midst of so much success, death lingered.

“I lost so many people from AIDS,” Scholder says, recalling the difficult time three decades later from her home in Los Angeles, California. “I was really burned out, and that experience in my community was shocking. In some ways I was reeling from it, you know, and maybe I still am.”

New York City represented a fresh start, so Scholder began packing her apartment. But, surrounded by what can only be described as an excessive number of books, she had to question it: “Was I really going to move all of these books three thousand miles into a tenement apartment in the East Village?”

The answer was yes.

And so Scholder did what thousands of U-Hauling lesbians had done before: she acquired more boxes. In went dozens of novels, anthologies, memoirs, and cookbooks. Scholder hardly cooked, and she figured her cooking would only decrease once she landed in New York City. In many ways, then, this strategy defied logic. In other ways, however, it made total sense. When Scholder pulled out The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book, for example, and considered its significance, there was no way it was getting left behind.

Soon after her cross-country move, Scholder followed in the footsteps of Toklas—that is, she started working on her own anthology cookbook: Cookin’ With Honey: What Literary Lesbians Eat. Contributors from all over the country responded to her call with enthusiasm, among them Eileen Myles, Harry Dodge, Minnie Bruce Pratt, Dorothy Alison, and Cheryl Clarke. (Suffice to say, it was a star-studded cast.) Recipes and anecdotes flooded Scholder’s mailbox—some serious, some not so much. She published with Nancy K. Bereano’s feminist imprint Firebrand Books, did the layout herself using InDesign, and enlisted longtime friend Rex Ray to design the cover—a departure from Firebrand’s typical “women’s studies aesthetic,” it is gold and black, a “kind of cool, cutting-edge literary rock-and-roll book,” Scholder says.

When Scholder pulled out The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book, for example, and considered its significance, there was no way it was getting left behind.

Reading through Scholder’s introduction now, it’s clear that Toklas was a major inspiration for the project. It makes sense—queer historians have since concluded that The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book was the first lesbian cookbook ever (the year was 1954), and amongst dykes who cook, it’s the stuff of legends. This is in part due to the fact that it wasn’t just a Rolodex of recipes; it was a memoir. The book chronicles Toklas’s life with the author and public intellectual Gertrude Stein, and, for Scholder, it felt like permission to do away with convention.

One of the best recipes in Cookin’ With Honey comes from writer and performer Laurie Weeks, who, Scholder says, was always trying to get off drugs and never had any food in her house. “Maybe she would have cheese, but no bread to make a melted cheese sandwich. And so you just put the cheese on a postcard, put it in the toaster oven, because isn’t it that gooey cheese that’s so delicious? So you just kind of scrape it off.” Reader, I give you “Nacho From the Edge.” This is the kind of unfussy, unhinged humor that runs through Cookin’ With Honey like a vein of gold. Mainstream cookbooks of the time instructed women on how to best approach perfection via the dinner table. Cookin’ With Honey and its queer contemporaries held up a mirror to the messy, myriad ways in which food is central to life—no matter how ugly it gets.

“It was nice to experience a collection that was centered around pleasure,” Scholder says. “And I think, on some level, I really needed that in my life at that time, to have a lighter way to produce something that also, I thought, was meaningful.”

Cookin’ With Honey wasn’t the only food project to deploy humor in a time of crisis. Perhaps the most famous example is “Get Fat, Don’t Die,” the long-running column authored by Beowulf Thorne for his AIDS-era zine, Diseased Pariah News. In his history of the column, Jonathan Kauffman writes that many patients with AIDS were dying due to malnutrition, or “wasting,” and thus caretakers were eager to fatten them up. Thorne’s column detailed recipes like “Gretchen Mae’s Fat Man’s Delight” and “Luke-O-Plakia’s Faceless Stroganoff” that, Kauffman says, “claimed the right to pleasure, but in each recipe was embedded an urgent appeal that recipe writing of the 1990s had dispensed with: Eat so you can survive.”

“Survival is political when you’re in a society that doesn’t want you to exist,” says Dr. Alex Ketchum, a queer historian who cofounded The Historical Cooking Project in 2013. In 2021, Ketchum curated an exhibit titled “A Recipe for a Queer Cookbook” at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, where she is an assistant professor. The exhibit poses the question on everyone’s mind: What makes a cookbook queer? Dr. Ketchum’s answer required the authors to self-identify as LGBTQ+, somehow touch on issues relating to the community in the book, and include instructions for preparing food or drink (not just metaphorical recipes).

But this is the question that haunts many of the gay and lesbian cookbooks from the 1970s through the ’90s, a heyday for the Women in Print movement, which frequently took on these projects while mainstream publishers were unwilling to bear the social, political, and financial risks. Through a loosely connected network of authors, agents, publishers, and bookstores, women circumvented the exclusionary tactics of big-name book people (read: men), opting instead to build their own systems. The alternatives were clear: In a moment of proposed censorship emblematic of the time, Selma Miriam and Noel Furie, cofounders of the lesbian-feminist group Bloodroot Collective and longtime owners of the Bloodroot restaurant in Bridgeport, Connecticut, remember being asked by their publisher to remove the word “political” from the title of the collective’s first cookbook, The Political Palate. They refused.

“We figured our first book should be ‘Political Palate’ because that’s what we were—we were political,” Miriam says. “But [Crossing Press] said no, we should change it. Meantime, we had a friend who knew how to set type, and she said, I’ll do it for you. So we did it ourselves.”

“Survival is political when you’re in a society that doesn’t want you to exist.”

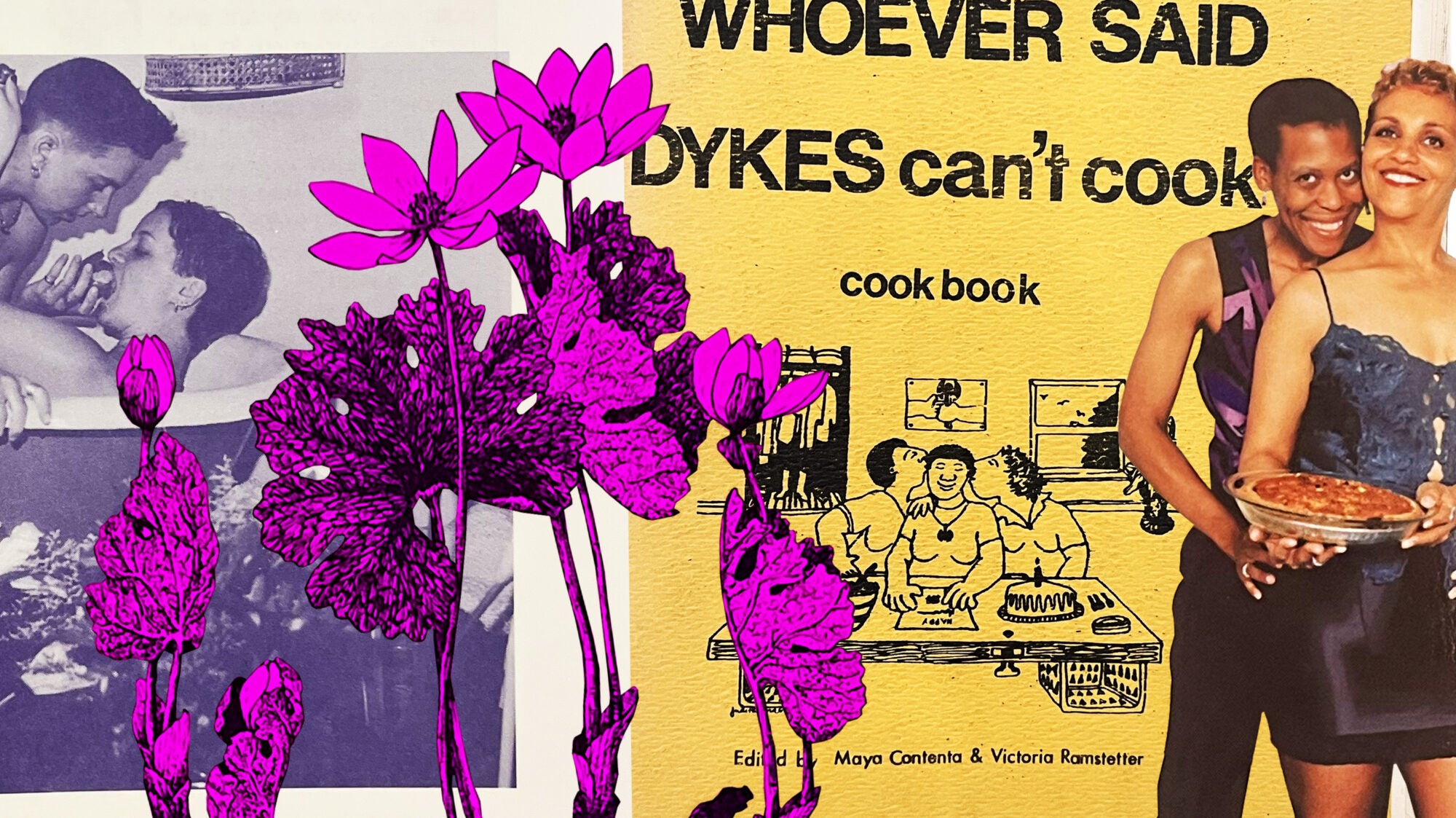

Other DIY cookbooks followed suit. In 1983, the Cincinnati-based Lesbian Activist Bureau published Whoever Said Dykes Can’t Cook?; in 1989, Leatherella Parsons solicited recipes from members of the International Association of Lesbian and Gay Pride Coordinators for Cooking With Pride (featuring copious stories from Parsons and dishes like “Wanda’s London Broil”). The next decade proved to be even bolder, with titles like The Lesbian Erotic Cookbook (tagline: “It’s Erotic in Nature”) in 1998 and, at the turn of the century, The Lesbiliscious Cookbook by Kim Gillow (with recipes from the now-defunct women’s group Camp Sister Spirit).

By the year 2000, the gay liberation movement was no longer top of mind. It was the era of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell and the Defense of the Marriage Act; it was a chapter in queer history defined more by assimilation than separatism. ACT UP and Queer Nation, two groups that defined the raging radicalism of the previous decade, no longer dominated the headlines.

And yet, if you flip to a page within The Lesbian Erotic Cookbook, you’ll most certainly be met by a naked woman. Recipes like “Chunky Butchy Borscht” (a classic borscht fit for the butch because it’s “strong [and] substantial”) and “Road to Ecstasy Applesauce Bread” (instructions: bring to the bathtub, surrounded by flowers, and nibble) inspire a certain degree of shamelessness. And there is nothing quiet about “Simple-Ass Pancake Mix,” deemed a “quicky” by the book’s author, Ffiona Morgan. These pages, then, offer a blueprint for a decidedly unapologetic queer life.

Is there something revolutionary about reclaiming a space that for so long has been the domain of the cisgender, heterosexual housewife? In an era dominated by anti-trans legislation, right-wing extremism, and the rise of the tradwife, the home remains a contested geography. Many would-be queer chefs no longer politicize their recipes; meanwhile, queer culture has been largely commodified. It can be difficult to see the political power of a title from a star cast member of Queer Eye; then again, the most powerful aspects of queer culture have never been those that mainstream culture readily absorbs.

If nothing else, the queer cookbooks of a generation ago taught us this: When your food—and your recipes—nourish a community that has been torn apart by homophobia, bad politics, and AIDS, at some point every meal starts to feel like an act of resistance. Sometimes getting fat is an act of war. Sometimes sheer survival is the most powerful form of revolt.