When seafood is slowly fermented with salt, the result is a briny, savory blast of umami that can transform dishes and inspire lifelong love affairs.

Open my cupboard, peruse my pantry, and inspect my fridge and you’ll count at least a dozen different bottles of fish sauce. They’re all testaments to the long affair I’ve had with the flavorful condiment that’s made from fermenting seafood and salt until it breaks down into a fragrant, inky liquid.

Fish sauce, called nuoc mam in Vietnamese, is part of my culinary DNA—and my family life is peppered with great fish sauce stories. One of the most memorable took place in the early 1960s, when my dad and uncle served as the governing military officials of two places renowned for fish sauce: Phan Thiet and Phu Quoc island. As my uncle once joked, “Your father and I protected one of Vietnam’s most precious things.”

After Dad retired from the military, he tried making a fish sauce concentrate that soldiers could dilute in the field. “If you’re patrolling in the jungle for a long time,” he recalled recently of his erstwhile experiments, “what do you want for a taste of home? Nuoc mam!” The idea didn’t catch on as a business, unfortunately.

When my family fled the 1975 Communist takeover of South Vietnam and resettled in San Clemente, California, mainstream American grocers didn’t carry fish sauce. Instead, we used soy sauce until we were able to buy a used Mercury Comet to make the three-hour round-trip drive to Los Angeles’s Chinatown to stock up. With fish sauce in hand, we felt more grounded, like we could be Vietnamese in America.

An adoration of nuoc mam led to my first cookbook’s working title, Pass the Fish Sauce. Alas, America wasn’t ready for it in 2006, when fish sauce was still largely unfamiliar here. So I went with Into the Vietnamese Kitchen. Behind the scenes, though, I did my part to spread the gospel: In the cooking classes I taught, I did fish sauce tastings with cucumber slices to help people better understand and appreciate it.

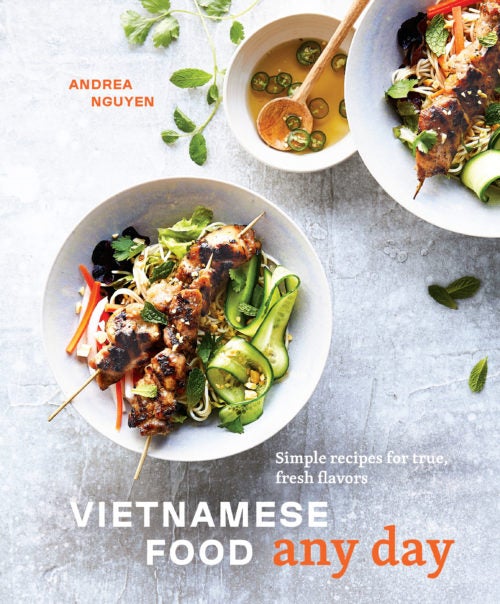

My sixth cookbook, Vietnamese Food Any Day, was released this year, and boy, have things changed. Cooks in 2019 are more adventurous and intrepid. People who attend my classes readily sniff and sample fish sauce from tasting spoons. They’re curious about different brands and want to know how to choose the best and how to use it well.

Here are a few pointers to help you along the way.

Navigating the fish sauce universe

Though fish sauce was an ancient Chinese, Roman, and Greek ingredient, nowadays it’s mostly associated with Southeast Asian cuisines. Depending on where you shop (a regular supermarket, an Asian market, Whole Foods, or online), the range of options varies. At a Southeast Asian or Chinese-Vietnamese market, you’ll see Thai nam pla, Filipino patis, and Vietnamese nuoc mam. Note that Korean markets, like H Mart, stock jeotgal and nuoc mam. Look online for more obscure Japanese shottsuru.

Thailand is the source of most of the fish sauces sold in the United States. Some of them are made in a so-called Vietnamese style that results in a subtle flavor that works well with the cuisine’s relatively mellow flavors, which I often describe as rolling hills. By comparison, the lusty, gutsy flavors of Thailand (think peaks and valleys) easily shine with bolder Thai-style fish sauce.

Filipino patis tends to be heavy-ish and lacking umami depth; it works well for Filipino food, but I’ve found it hard to deploy for Viet and Thai cooking.

In my own cooking, I mainly use Viet Huong’s Three Crabs, Red Boat, and Megachef (the blue-label bottle is easier to source in America). They’re made in the Viet style and are versatile; you can use them to finesse flavors across cuisines. I know without a doubt they’ll work for Viet food. When deploying nuoc mam for Thai dishes, I compensate for the more savory nam pla by initially using less sugar than a recipe calls for; if I don’t arrive at a solid Thai flavor profile, I’ll add more sugar. Nuoc mam is also fine for fermenting kimchi and seasoning Filipino sinigang.

Sweet-savory notes make many Asian dishes rock, but fish sauce that is on the sweeter side may jet Western dishes to Southeast Asia. When I want to amplify the umami depth of marinara sauce, Caesar salad, chili con carne, salsas, and posole, I’ll add dashes of fish sauce such as Red Boat’s, which is devoid of sweeteners.

Buying and storing fish sauce

If you’re in a mainstream grocery store, like Kroger, Whole Foods, or Publix, or in an indie market, check the Asian food section for Red Boat, Three Crabs, Thai Taste, and Dynasty (this is likely Megachef in a private-label disguise). Commonly found Thai Kitchen is a bit flat-tasting but fine in a pinch.

Refrigerate fish sauce if you only use it occasionally or if the smell bothers you. Keep it in the cupboard if you employ it several times a week or more. Fish sauce starts out as a clear amber liquid when it’s first produced but can darken and look inky over time, becoming saltier, funkier, and more concentrated as the liquid evaporates. When that happens, just use a little less than usual.

Employing fish sauce like a master

Read the nutrition labels and check the sodium level, which may range between 1,200 and 1,800 milligrams of sodium per tablespoon, depending on the brand. To prevent fish sauce from overwhelming food with its funk, I often combine it with salt; the two impart different kinds of savoriness to foods. If your fish sauce doesn’t have a built-in sweetener and/or an umami booster, like hydrolyzed vegetable protein, you may need a little sugar (or maple syrup).

Many people initially experiment with fish sauce by making Viet nuoc cham dipping sauce for noodle dishes and rice paper rolls. For simple foods, like smoky grilled eggplant, combine two parts fish sauce with three parts water and add thinly sliced chiles and perhaps minced garlic.

You can also try making canh, a broad category of Viet-style quick soups that are enjoyed at everyday meals. They’re typically prepared with water (not broth!) and rely on gently sautéed onion, fish sauce, and salt for foundational depth. Among my favorites is a versatile gingery greens and shrimp soup, which is great for dinner or lunch.

I often add fish sauce to oyster sauce to enhance the latter’s sweet, briny nature, which is supposed to come from actual oysters but often does not. For my take on shaking beef (thit bo luc lac), the meat is marinated with oyster sauce, nuoc mam, and soy sauce. Fish sauce plays a supporting role, but without it, the dish would lack gravitas.

You don’t have to rack up family anecdotes to appreciate nuoc mam. You just need to keep it on hand and use it often.

Lead photograph by Andrea Nguyen. Other photographs by Aubrie Pick.

Ingredients

- 1¼ pounds extra-large or jumbo shrimp, peeled and deveined

- 1⅓ cups coconut water

- 1½ tablespoons sugar, plus more as needed

- 1 tablespoon Caramel Sauce (recipe follows), or 1½ teaspoons molasses

- 1½ tablespoons fish sauce, plus more as needed

- 2 tablespoons virgin coconut oil

- 1 large shallot, halved and sliced

- 3 large garlic cloves, sliced

- Recently ground black pepper

- 1 green onion, green part only, thinly sliced

- Caramel Sauce

- 2 tablespoons water, plus ¼ cup

- ⅛ teaspoons unseasoned rice, apple, or distilled white vinegar (optional)

- ½ cups cane sugar

My niece Paulina requested this savory-sweet comfort food from southern Vietnam, a region where cooks use coconut milk and coconut water for a sunny array of dishes. I happily obliged because it’s delicious and involves a nifty technique—coconut water is reduced with other ingredients until it caramelizes a bit to create a lovely syrupy sauce. Enjoy tôm rim nước dừa with rice and a simple vegetable, like charred Brussels sprouts. Choose a large skillet or sauteuse pan with a light interior to easily monitor the color changes during cooking.

Caramel Sauce

- Fill the sink (or a large bowl or pot) with enough water to come halfway up the sides of the saucepan.

- In the saucepan, combine the 2 tablespoons water, vinegar (if using), and sugar. Set over medium heat and cook, stirring with a heatproof spatula or metal spoon; when the sugar has nearly or fully dissolved, stop stirring. Let the sugar syrup bubble vigorously for 5 to 6 minutes, until it takes on the shade of light tea. Turn the heat to medium-low to stabilize the cooking. Turn on the exhaust to vent the inevitable smoke. (Don’t worry if sugar crystallizes on the pan wall. But if things get crusty in the bubbling sugar syrup, add another drop of vinegar to correct it.) For even cooking, you may occasionally lift and swirl the saucepan.

- Cook the syrup for about 2 minutes longer, until it is the color of dark tea. The next 1 to 2 minutes are critical because the sugar will darken by the second. Monitor the cooking and, to control the caramelization, frequently pick up the saucepan and slowly swirl the syrup. When a dark reddish cast sets in—think the color of Pinot Noir—let the sugar cook a few seconds longer to a color between Cabernet and black coffee. Remove from the heat and place the pan in the water to stop the cooking. Expect the pan bottom to sizzle upon contact.

- Leaving the pan in the sink, add the remaining ¼ cup water. The sugar will seize up, which is okay. When the dramatic bubbling reaction stops, return the pan to medium-high heat, and cook briefly, stirring to loosen and dissolve the sugar.

- Remove the pan from the heat and return to the water in the sink for about 1 minute, stirring, to stop the cooking process and cool the caramel sauce to room temperature.

- Use the sauce immediately, or transfer to a small heatproof glass jar, let cool completely, and then cap and store in a cool, dark place indefinitely.

Shrimp

- Pat the shrimp with paper towels to remove excess moisture, and set aside.

- In a medium bowl, combine the coconut water, sugar, caramel sauce, and fish sauce and stir to mix; taste and make sure it’s pleasantly salty-sweet. It will cook down later and intensify but use this opportunity to check the flavor. If needed, add up to 1½ teaspoons sugar or fish sauce, or both. Set aside.

- In a skillet or sauteuse pan over medium heat, melt the coconut oil. When the oil is barely shimmering, add the shallot and garlic and cook, stirring frequently, for 3 to 4 minutes, until the garlic is pale blond. Remove from the heat and, once the cooking action subsides, add the coconut water mixture.

- Return the skillet to high heat and bring to a boil. Cook, without stirring, for 10 to 14 minutes, until reduced to between ⅓ and ½ cup, a bit thickened, and slightly darkened. Add the shrimp and continue cooking at a swift simmer, stirring frequently, for 3 to 5 minutes, until the shrimp curls up and cooks through and the sauce is slightly syrupy. (Expect the shrimp’s natural juices to release, thin out, and flavor the sauce.) If the shrimp cooks too fast, remove it from the pan, let the sauce cook down, and then return the shrimp. Remove from the heat, season with lots of pepper, and stir in the green onion. Let sit for 5 minutes for the flavors to settle and deepen.

- Transfer the shrimp to a shallow bowl or plate and serve.

Ingredients

- 2 cups packed thinly sliced green cabbage leaves

- ½ small jicama, peeled and cut into medium-thick matchsticks

- 1 (16-oz) unripe mango, peeled, pitted, and cut into thick matchsticks (double the width of the jicama)

- 1 ime

- Unseasoned rice vinegar as needed

- 1½ tablespoons sugar

- 1½ tablespoons fish sauce, or 1½ tablespoons soy sauce plus ¼ teaspoon fine sea salt

- 1 small garlic clove, put through a press or minced and mashed

- 1 Thai or small serrano chile, finely chopped, with seeds intact

- ¼ cups packed coarsely chopped fresh mint or basil

- ⅓ cups finely chopped unsalted roasted peanuts or cashews

Many people assume that an unripe mango is not ready for prime time, but to me, it’s an opportunity to make gỏi xoài (mango salad). The traditional rendition includes cooked shrimp and fatty pork, but I’ve found that dropping the proteins not only makes the salad less fussy (read: faster to make) but also shifts the focus to the produce and highlights the tropical flavor combinations that are central to Vietnamese cooking. The decluttered version is lighter, brighter, and easily adapted for vegan diners.

At the store, choose a rock-hard, unripe mango (one with all or mostly green skin). Store it in the fridge to prevent ripening. When you’re ready to make the salad, peel it with a knife or vegetable peeler, removing all vestiges of the firm green skin. The remaining flesh sweetens slightly and softens in the salad. For the jicama, choose a small, blemish-free one (ideally no larger than a grapefruit); it will be sweeter and less starchy than older, bigger ones.

- In a large bowl, combine the cabbage, jicama, and mango and set aside. (The vegetables and fruit can be stored, covered, in the refrigerator for up to 24 hours.)

- Using a fine rasp grater, such as a Microplane, zest the lime directly into a small bowl. Squeeze the lime to get 2 tablespoons of juice; if you’re short, add vinegar to make up the difference. Add the lime juice to the zest and then add the sugar (the amount depends on your palate and the mango—use more if the mango is sour). Stir to dissolve the sugar, then taste and add more sugar, if needed, for a strong tart-sweet finish. Add enough of the fish sauce to arrive at a bold, salty-tangy finish. Add the garlic and chile, stir, and then set the dressing aside.

- Toss the vegetables and fruit well with the dressing, mint, and peanuts, until the cabbage and jicama soften slightly. Transfer to a shallow serving bowl, leaving excess dressing behind.

- Serve immediately.

Ingredients

- 1 tablespoon canola or other neutral oil

- ½ medium yellow or red onion, thinly sliced

- 5½ cups water

- Fine sea salt

- 1 tablespoon fish sauce, plus more as needed

- 1 (8-oz) bunch mustard greens, coarsely chopped, including tender stems

- 12 large shrimp, peeled, deveined, and cut crosswise into thumbnail-width chunks, or split horizontally into symmetrical halves

- 1½ teaspoons finely chopped peeled ginger

- Recently ground black pepper (optional)

A typical component of an everyday Vietnamese meal, fragrant, wholesome, and fast soups like this one are called canh. Surprisingly, they’re typically made with water and rely on gently sautéed onion, salt, and fish sauce for foundational depth. What often defines canh is a ton of leafy greens, cooked in the pot to contribute their flavor and nutrients. A little protein is dropped in for savory flair. At the Viet table, canh is not just a first course—you can help yourself to it throughout a meal to refresh your palate. This nimble soup plays well with other dishes, but you can make a light meal of it, too. Just add warm bread and butter.

Instead of mustard greens, use another bold-flavored leaf, such as turnip greens or the radish tops left over from making pickles. Opt for spinach for a milder taste, or combine complementary greens, like kale and mustard.

As pictured, corkscrew-shaped shrimp result from halving them horizontally. Not fond of shrimp, or maybe it’s too expensive? Use a six-ounce fish fillet, such as tilapia or rockfish. Cut the fillet into bite-size pieces to add to the soup.

- In a 3- or 4-quart saucepan over medium heat, warm the canola oil. When the oil is barely shimmering, add the onion and cook for about 4 minutes, stirring, until soft and sweetly fragrant. Add the water, ½ teaspoon salt, and fish sauce, then turn the heat to medium-high and bring to a boil. Adjust the heat to maintain a vigorous boil for 3 to 5 minutes to develop flavor. Add the greens, stirring them for even cooking. When the greens are very soft and cooked through, about 5 minutes, add the shrimp and ginger. When the shrimp are opaque and cooked through, 1 to 2 minutes, remove from the heat and let rest for 5 to 10 minutes, uncovered. Taste and add additional salt or fish sauce, if needed.

- Serve the soup in a communal bowl or ladle into individual serving bowls. Sprinkle with pepper for a final spicy burst, if you like.