If you really want to learn how to cook something, settle in and watch an old person do it for a while.

Everyone has a way of unwinding at the end of the day. For some people, it might be bullet journals, or drinking a Genessee Cream Ale, or scrolling through an Instagram feed of Japanese bread packaging. For me, it’s queuing up some videos of old people cooking things slowly.

As far as I can remember, this sprang from a video on the New York Times website of the late Marcella Hazan at age 89. She’s invited food writer Mark Bittman into her Florida home for a lunch cooked by herself and her husband, Victor. Victor shuffles gently across the kitchen with a pot of pasta water. Marcella sits at the kitchen table painstakingly cutting tiny slits in the bottoms of endives so that even the dense spots will cook through. Then, endives conquered, she lights a hard-earned cigarette. “In a few months, I will be 90,” she sighs. “It’s too much.”

I found the relaxed pace of the cooking (apparent even in this particular tightly edited video) soothing and refreshing, and it sent me diving into the Internet’s vault of old people cooking videos. Some were vignettes that news organizations had made of aging chefs and cookbook authors, and some were shaky, amateur tributes by kids or grandkids, trying to capture recipes that had been guarded for generations. In one, entitled “Carla’s Tortellini,” a 90-year-old woman shows her granddaughter how to make hundreds of tiny meat-filled tortellini. Like Marcella, Carla alternates between instruction and self-reflection. “I made a beautiful life for myself,” she says wistfully between tortellini.

The clips are all completely void of suspense or excitement—foils to all the cutthroat, adrenaline-pumping competition shows and snappy 30-second hands-and-pan videos of our era.

In addition to this topical, rhythmic charm (it’s nice to watch a grandmother make manti with her son as her granddaughter narrates!) value of these videos, they offer a few advantages that you rarely find in other forms of visual food media. For one, when a recipe makes its way into a food magazine or onto a TV show, it’s often been simplified and streamlined for the audience at hand, taking into account both their time limitations and their ingredient limitations (you can’t find galangal or sheep’s milk ricotta at every grocery store in the United States). But when Carla makes tortellini, the flour has to be recently milled, and it’s not negotiable.

In a YouTube clip labeled “Making Khao Soi with Chow’s Aunt,” an unnamed woman shows how she makes khao soi in her small home kitchen, not with premeasured quantities, but with bowls of coconut milk and light soy sauce that she dips into periodically, showing, as she goes, how wet the noodles should be, how dark the sauce should be, and how thinly sliced the scallions should be.

In a PBS clip showing how gumbo z’herbes is made at legendary New Orleans restaurant Dooky Chase, a 95-year-old Leah Chase navigates the kitchen with the help of a cane, narrating the process. In a triumph against the pragmatism and efficiency of test kitchens everywhere, Leah rattles off a list of almost a dozen types of herbs and greens that may or may not make it into the dish on a given day. The important thing, she says, is to use an odd number of greens. “Even numbers are bad luck. So you put uneven numbers of greens.”

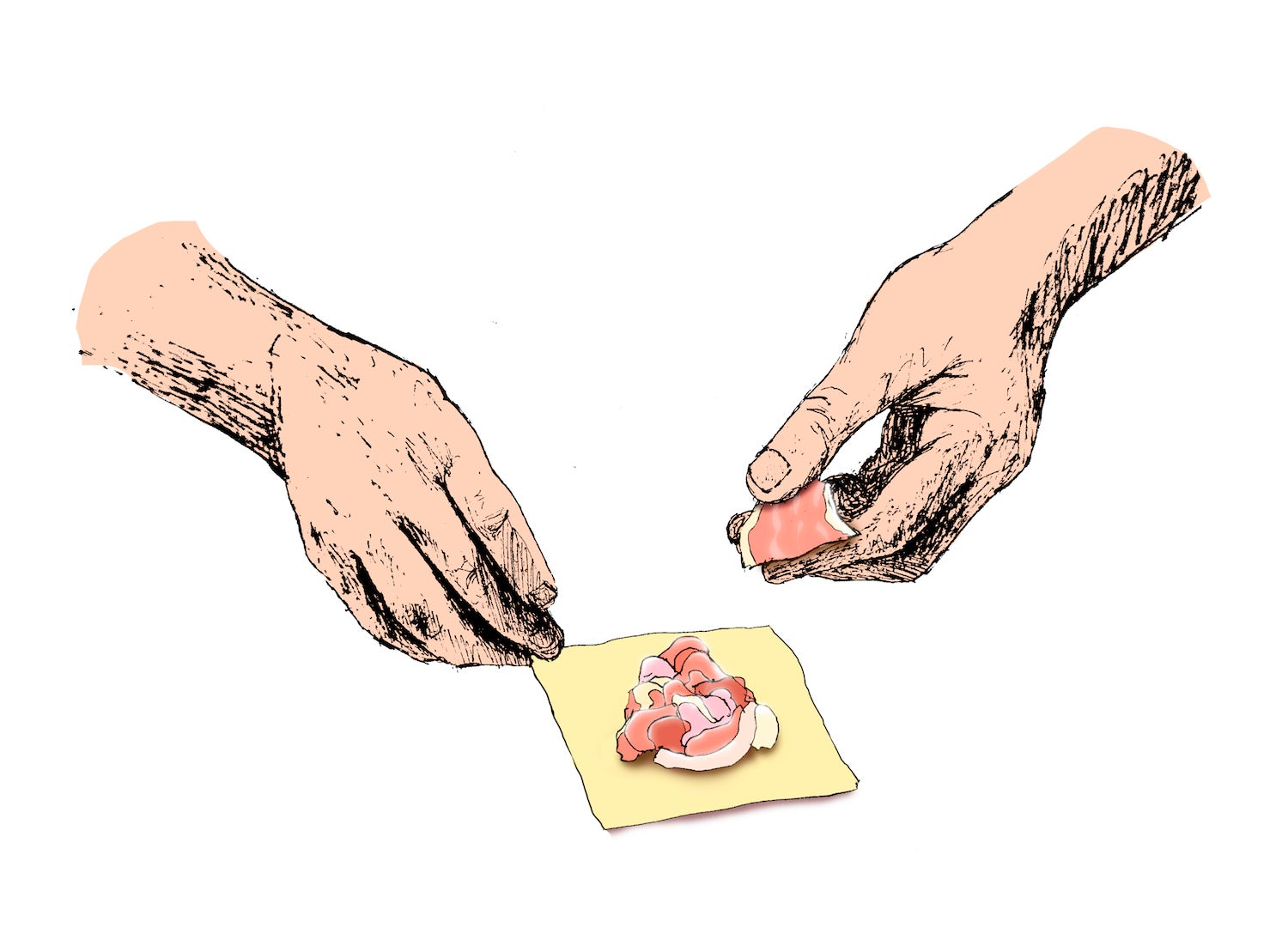

The medium works best for techniques that are hard to visualize from the written recipe—dishes where there’s some kind of tricky handiwork involved—wending softened cabbage leaves into tidy cylinders full of meat, folding dumplings into tightly sealed balloons, or stuffing seasoned sausage under the skin of a chicken wing. Grandma stuff. These are motions you can sort of describe in words, but until you see someone do it (or better yet—do it yourself), it’s hard to gauge how generously you should stuff the dumpling or how firmly you need to pull the elastic chicken skin.

But even better than creating visual instruction, these slowed-down, shaky hand videos give you a realistic idea of what it will be like to cook something you’ve never cooked before. There are no Food Network television tricks for making it all look more effortless than it is. At the end of the khao soi video, Chow’s aunt turns off the stovetop flame, laughs with relief, and wipes away some sweat.

We’re in the middle of a cultural moment where the most viral food videos tend to be sleek time lapses that emphasize the recipe’s low-effort-to-high-payoff ratio. We’re being sold the idea that at any given moment, we’re just a minute away from knowing how to make flaky, buttery baklava to rival the Greek place around the corner or crispy egg rolls that are as good as the takeout spot a few blocks away. In reality, becoming a good cook takes time. That’s why a lot of them have gray hair.