Modern critics of the prolific food writer might have more in common with her than they realize.

It was 1954, and The Art of Eating: The Collected Gastronomical Works of M. F. K. Fisher had just been released. The bound collection of five previously published books featured an introduction by Clifton Fadiman. Fisher’s author photo had been taken by photographer and Dadaist Man Ray.

The reviewers were starry-eyed. In the New York Herald Tribune, J. T. Winterich called her “one of the haute cuisine gastronomes of all time.” While other female food writers of the day almost exclusively wrote fussy recipes or offered sage advice about home economics, Fisher wrote about her own charmed life, world travels, and many elaborate meals using food as a metaphor for the human experience. In her 15 years of writing thus far, she had virtually invented the genre of modern narrative food writing, and her adoring critics and many fans could not get enough of it.

But Fisher was conflicted by the fanfare. The writing, it turned out, wasn’t serious or important enough to merit all the fuss. Or at least not in the eyes of the author. “I feel quite plainly repelled by the whole thing, and I wish I’d never agreed to it,” she told a friend in a letter in 1954 about the adored collection of her writing. “Warming up a cold corpse as far as I’m concerned, for the woman who wrote those books has been dead for years.”

Why would M. F. K. Fisher, arguably the most famous food writer of the twentieth century, hit her 40s and want to quit? Middle-aged and a single mother to two young girls, Fisher was lonely and overwhelmed. Great reviews had not translated into meaningful book sales (such was and still is the industry), and she was a working writer who needed a regular paycheck. She felt her usual subjects—food, wine, and other activities bundled into a breezy category called “pleasure”—were as stale as a week-old miche. Her writing persona, the M. F. K. Fisher that you love (or love to hate), and the person that hungry fans quote on social media under portraits of winter pears and creamy floral tablescapes, was such a heavyweight that she longed to discard it completely.

“I feel quite plainly repelled by the whole thing, and I wish I’d never agreed to it.”

Though she was praised as a singular talent in the field, the subject of food that she poured so much of her early life into was just a means to an end: Fisher really wanted to break out of food entirely and publish work on a wide range of topics, fiction included. She fantasized about killing off the M. F. K. Fisher everyone knew as a food writer and reentering the scene as someone entirely different.

In a letter written to her sister Norah in April 1952, Fisher wondered: “Should I quietly hold a private funeral? Should I give the coup de grace to some 25 years spent developing a minor talent?” But she was worried about how abandoning her career might affect her emotionally and concerned that her current sense of self was too deeply bound to her literary persona.

She had tried fiction before—with little success. Fisher and her second husband, Tim, had collaborated on two novels. One sat in a drawer; the other, published in 1939 under the pseudonym Victoria Berne, had received scant attention. Ten years later, in 1949, she’d tried again. Not Now but Now was a story about a female heroine, Jennie, who appeared unaged in different eras and places. “I think we can dismiss the whole thing,” Hamilton Basso wrote in The New Yorker, remarking on the “brittle preciousness” of Fisher’s writing style.

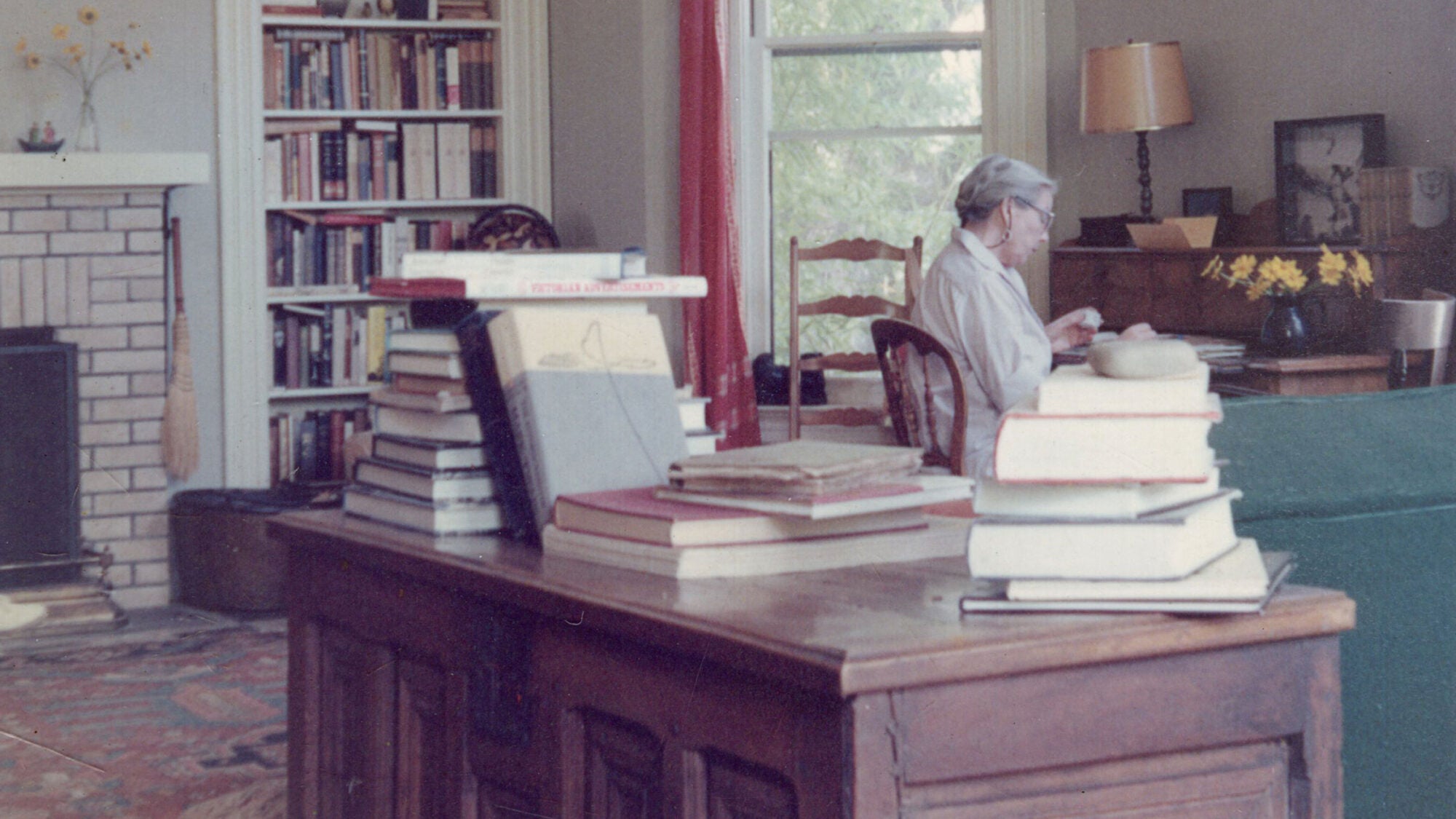

MFK Fisher in 1954

The negative backlash had stung, as had the realization that she wasn’t cut out to write literary fiction on par with her beloved idols Colette and Virginia Woolf. It left a painful open question about what to do next.

“Do I marry M. F. K. Fisher and retire with him-her-it to an ivory tower and turn out yearly masterpieces of unimportant prose?” she had asked her psychiatrist, George Frumkes, in a letter written in 1950, around the time her ennui started brewing. “Do I study yoga? Chinese? The making of Bombay curries? Or just myself?”

You could call this a midlife crisis or dismiss Fisher’s angst as a mid-20th-century women’s issue. You could label her desire to reinvent herself as the musings of a melancholy dilettante.

That’s what the Fisher haters would do. Every famous writer has them: naysayers and eye-rollers. But Fisher seems to inspire more vitriol than many, even half a century after the fact. The comments can be cleaved into the personal (she was snobby and narrow-minded) and the prose oriented (her writing was overly pretty and precious). In 2014, the late writer Joshua Ozersky decried Fisher as nattering and elitist, basically the source of inspiration for all the bad food writing in existence. He ended his public takedown on Medium with the line “M.F.K. Fisher must die.”

Every famous writer has them: naysayers and eye-rollers. But Fisher seems to inspire more vitriol than many, even half a century after the fact.

Isn’t it funny to learn that she felt the same way? That even though she’s been placed on a high literary pedestal, Fisher was besieged by the same creative neuroses, doubts, and practical problems that haunt many writers?

In the recently published collection Women on Food, editor Charlotte Druckman and writer Sadie Stein commiserate over their shared “lack of love for a food writer held up as the ultimate, shining example of her profession.” But when I told Stein how self-critical Fisher had been, she was sympathetic. “I have no difficulty believing M. F. K. Fisher had normal doubts and fears; she was a real person, and I can’t imagine any writer who doesn’t have a complicated relationship with the persona she creates.”

In the end, rather than tossing her food-writing career aside, Fisher became more resolute. She continued to churn out prose quickly (she hated revising), and negative opinions went unread or were dismissed (they didn’t understand her). She hoarded praise like a protective layer of fat.

After being regularly in print for three decades, Fisher became more commercially popular in the late 1960s, as more Americans began to enjoy global travel and food. She became friends with James Beard, Julia Child, and other culinary talents who helped make gastronomy popular for the masses. She wrote the Time Life book The Cooking of Provincial France, which was mailed to 500,000 subscribers in 1968, on the cusp of her 60th birthday.

Fisher continued to write into old age, but many essays were careful duplications of pieces that had been written decades before, then refashioned and republished under a new title. It was a sly bit of self-plagiarism that Fisher, her editors, and her publishers were aware of and didn’t care about—they just needed more Fisher work to sell.

Rather than killing off M. F. K. Fisher, she had become her.