The author helped define an era of simple, unglamorous home cooking, leaving behind a signature recipe that may outlive us all.

“The word ‘power’ ruins my idea of breakfast,” Marion Cunningham once told Sheryl Julian of the Boston Globe. “The whole concept is spoiled by the fact that we should be negotiating. Breakfast should be a friendly, gentle moment in life.” The quote was a quintessential Marion-ism: quippy and perspicacious, with all the delivery and social commentary of a perfect joke.

It was October 7, 1987. President Ronald Reagan was wrapping up his second term. The 40-year-old real estate magnate Donald Trump had closed on his third casino, the Taj Mahal, in Atlantic City. And the titans of finance, their wallets all the fatter from Reagan’s slashing of top tax rates, were hammering out deals over eggs Benedict and white tablecloths at places like the Regency Hotel on New York’s Park Avenue. America was drunk on the greed-is-good ethos. Famously immune to short-lived trends, Cunningham was uncharmed.

Cunningham—one of the grande dames, along with Edna Lewis and Alice Waters, of American cooking—was imminently practical. Visiting food journalists who came to profile the beloved cookbook author always marveled at her electric stove and humble kitchen in her family home in Walnut Creek, California. No Viking stove, no Sub-Zero refrigerator. Her most notable indulgence was keeping two Toastmaster waffle irons on hand. “Nobody wants to wait for waffles,” she said of the redundancy.

The writing was smooth, vibrating with a sort of melodic everyday poetry, and even the recipes were warmly inviting in name: Bridge Creek Fresh Ginger Muffins, Heavenly Hots, Cinnamon Butter Puffs, Chinese Tea Eggs, and Lemon Zephyrs.

Waffles became something of a Cunningham emblem. Renowned for her best-selling revision of The Fannie Farmer Cookbook in 1979, she was 65 years old when she published the first cookbook under her own name, The Breakfast Book, with Knopf, in 1987. In the introduction, she said that there were almost no books on breakfast, a meal she loved for its “honest simplicity” and for remaining “pure” amid all the stylish food trends—it was a reclamation of sorts, a revolutionary one in its own understated way. The writing was smooth, vibrating with a sort of melodic everyday poetry, and even the recipes were warmly inviting in name: Bridge Creek Fresh Ginger Muffins, Heavenly Hots, Cinnamon Butter Puffs, Chinese Tea Eggs, and Lemon Zephyrs. Cunningham never oversold a recipe with excess verbiage. Her pancakes were “Plain Pancakes,” so you could only believe her when she asserted with matter-of-fact confidence that they were better than all the others she tried.

The recipes were so foolproof that even a kid could pull them off. Every Mother’s Day, I would leaf through the book to make my own mother breakfast in bed, delivered on a tray with a small vase of flowers. But it was her much-imitated yeasted waffles, in which the batter is mixed the night before and then eggs and baking soda are added just before cooking, that signaled the revival of the gentle and communal American breakfast. She credited them to an early Fannie Farmer cookbook, but her recipe added sugar, adjusted ingredient amounts and method, and, instead of whipped egg whites, used baking soda for extra leavening without a whisk workout. Crisp, light, and conveniently make-ahead, they became an enduring classic.

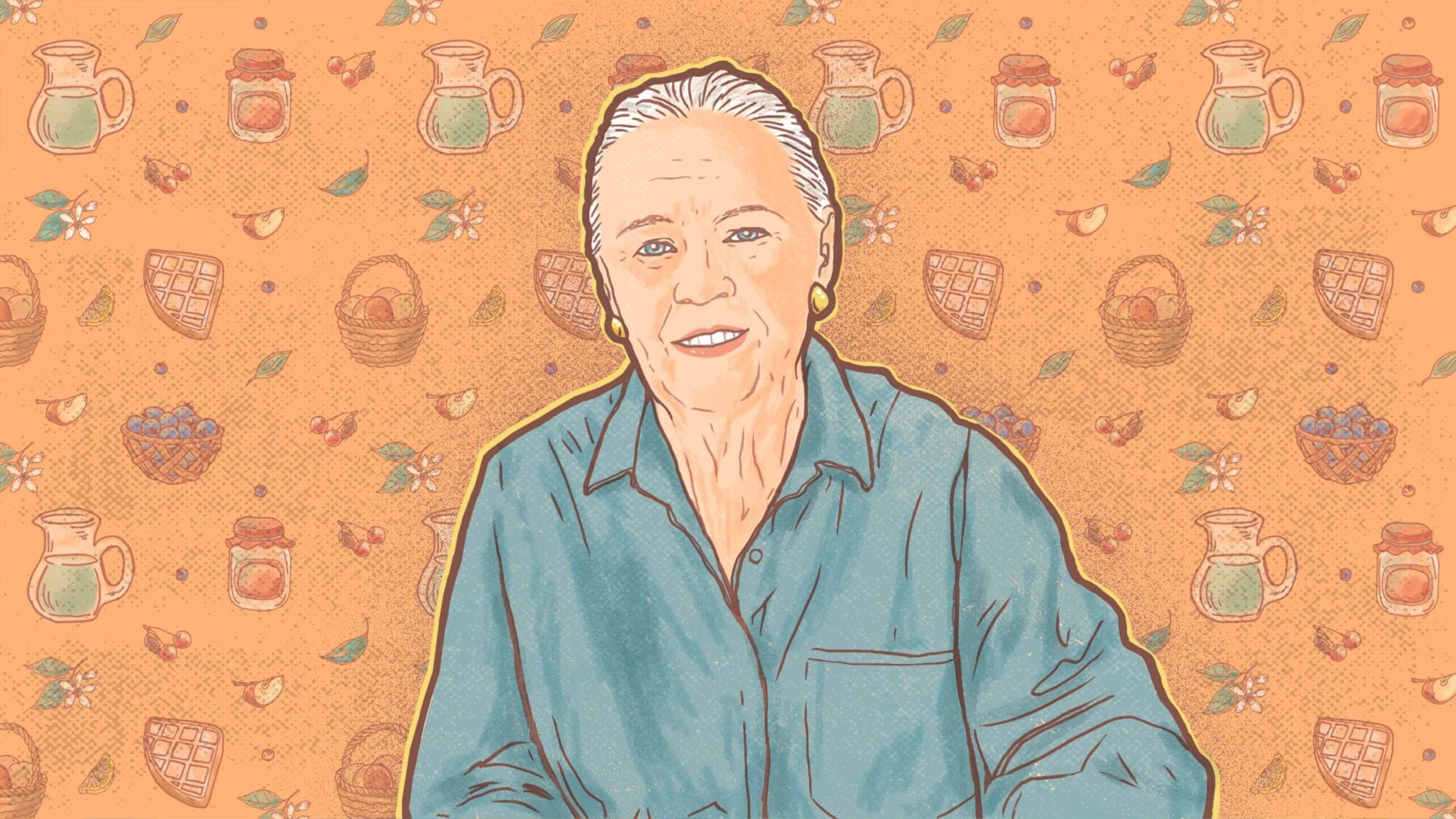

Cunningham was an American original in her own right. Tall, with piercing blue eyes, a sleek silver bun, and tasteful jewelry, the Californian cut a striking figure. “[She] makes senior citizenship seem like nothing more than a few wrinkles. And even her wrinkles are elegant,” remarked the Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s admiring food critic John Kessler.

During World War II, years before she became a famous cookbook author, she worked at a Walnut Creek service station while her husband served as a Marine. She changed oil and reset spark plugs, with designs on buying her own station, but when her husband returned and complained that she always smelled like “40-weight oil,” she let that dream go. Instead, she developed crushing paranoia and agoraphobia, and, along with her medical malpractice lawyer husband, a serious drinking problem, keeping a small bottle of gin in her pocketbook—an unfortunate family tradition, as her own father was an alcoholic with a rage problem.

The food writer Kim Severson, in her book Spoon Fed, alluded to “terrible things” at home. Whatever pain Cunningham endured or her own sins, she kept them mostly to herself, dropping a hint on occasion. “He doesn’t like homemade bread and he doesn’t like vegetables,” she once said of her husband, Robert, whom she’d met in kindergarten. “The only green thing he says he likes is money.”

Cunningham was a depressed, hypochondriac, alcoholic housewife well into her forties. But in America, in a correct reading of F. Scott Fitzgerald, redemption is always around the corner.

White-knuckling her way out of her crippling fears, Cunningham boarded a plane when she was 45 years old and left her home state for the first time to attend a two-week cooking class in Oregon with a personal hero, James Beard. In a cinematic twist of fate, Beard took a liking to her and an appreciation for her palate and cooking instincts, and he asked her to assist him with subsequent classes, which she did for more than a decade. “James Beard was one of her really great friends,” Julia Child told the Boston Globe. When the legendary Knopf editor Judith Jones asked Beard to recommend a home cook who could overhaul the then sadly dated Fannie Farmer Cookbook, he pushed for Cunningham, sharing her letters with Jones, who “loved the tone” of them. The cookbook, first published in 1896 as The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book by Fannie Merritt Farmer, had since gone through a number of disfiguring revisions, but Jones was confident America would embrace the right update. Cunningham was so nervous that she hoped she wouldn’t get the gig, but it wasn’t to be. So, in her early fifties, she set out to redeem an American classic.

Cunningham’s original revision of The Fannie Farmer Cookbook was something of a disaster. She estimated it would take her one year but it took five, and the small advance ran out before she finished testing and retesting all the hundreds of recipes, cutting some and adding others. “I never want to know what that book cost me,” she told the Boston Globe. But the book, released in 1979, went on to sell nearly a million copies, and Cunningham discovered her calling. “I found I loved testing recipes,” she said. “I never learned so much in my whole life. When the book was turned in I was depressed.” Jones’s next request was to create, from scratch, The Fannie Farmer Baking Book, which debuted in 1984. Along the way, Cunningham became the “butter of the food world,” according to Alice Waters in the Associated Press. She introduced Beard to Chez Panisse. She took monthslong trips to Europe and then to Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China with Waters and Cecilia Chiang. One of her closest friends was Chuck Williams, who went on to found Williams-Sonoma.

Back when America was besotted with French food and the organic movement, Cunningham’s commitment to iceberg lettuce and dowdy American food actually was exceptional.

“Marion Cunningham epitomized good American food,” Jones told the Los Angeles Times. “She was someone who had an ability to take a dish, savor it in her mouth and give it new life.” She’d given herself a new life, too. Despite her husband’s improbable protestation that she was “no fun” without a few cocktails, she kicked that drinking habit at 49, turning to coffee instead, and took up swimming and walking her golden Labrador Retriever daily. She bought a Jaguar—an uncharacteristic impracticality, given the car’s frequent service appointments—with her first royalty check from The Breakfast Book and drove it to meet the San Francisco Chronicle dining critic Michael Bauer five nights a week at a different Bay Area restaurant some 70 miles away.

For all the glamour of her new life, Cunningham’s bone-deep curiosity for home cooking abided. Early on, the once car-mechanic hopeful understood the technical aspects of the culinary arts. For The Fannie Farmer Baking Book, she devoted six months to researching the science of ingredients, consulting with flour technologists, microbiologists, and chocolate experts.

She also understood that psychology was just as important for a successful recipe. At the supermarket, she would peer into the baskets of unsuspecting shoppers and pepper them with questions about their cooking plans. She and Jones put together a 35-question survey to inform Learning to Cook with Marion Cunningham, and she held classes for complete novices to suss out problem areas in recipes for the uninitiated—like a student who gave up on a recipe when she couldn’t find “soft butter” in the market. She went on to publish The Supper Book, Cooking with Children, and Lost Recipes.

Today, it is quite typical to pronounce one’s love for American ordinariness—diners and ranch dressing and whatnot—as if it’s some sort of act of courage. Back when America was besotted with French food and the organic movement, Cunningham’s commitment to iceberg lettuce and dowdy American food actually was exceptional. Those yeasted waffles would outlast power breakfasts and the low-fat dictums of 1987—when she passed away in 2012, the recipe was printed in newspapers around the country, like the ringing of church bells. We’ve got many more breakfast cookbooks now. Tina Ujlaki, the great former Food & Wine executive food editor, once told me that “everyone has appropriated the Marion Cunningham waffle.” I have to imagine Cunningham was quite pleased with that.

What We Talk About When We Talk About American Food. In this column, Mari Uyehara covers American food at unique cultural moments and historical turns, great and small.