How a chef, cookbook author, and recovering medieval-history scholar became obsessed with the world of Carolina Reapers, Trinidad Scorpions, and the deadliest ghost peppers.

If you had been eavesdropping on the kitchens of Weehawken, New Jersey, one sunny afternoon in June, you might have overheard a truly odd noise. If you’d tilted your head one way, it would’ve sounded like a handful of people hacking their lungs up, on the verge of miserable death from some long-gone 18th century industrial disease. Tilt the other way, and it might have seemed like ecstatic laughter, the incessant cackling of the maddest angels high on heavenly herb.

In truth, the cacosymphony was both. Maricel Presilla—the chef, scholar, author, and winner of two James Beard Foundation awards, one for her cooking at Hoboken’s Cucharamama, the other for her 912-page cookbook Gran Cocina Latina—had just set a half-ounce of chiles de arból, the dried, sticklike, very hot Mexican pepper, onto a comal atop her six-burner Garland stove. Within seconds, invisible fumes had filled the room, lashing our throats with aerosolized capsaicin, the chemical that makes chiles hot. We coughed uncontrollably. It was hilarious. We laughed uncontrollably, until we started coughing again, and cackling again.

Earlier, Presilla had told me that the ancient Cuetlaxtlans had executed “Aztec officials they didn’t like” using just this method—asphyxiating them with toxic chile smoke. With her easy, sharp smile, wavy blonde hair, and short stature, Presilla had seemed so friendly, but was she secretly trying to kill me? Was that sly smile a villain’s smirk?

Man, I hoped not: I really wanted to try this Oaxacan tomatillo salsa we were making—and Presilla’s poblano-larded version of Spanish tortilla—before I died.

A woman selling assorted Andean peppers at a market in Piura, Peru.

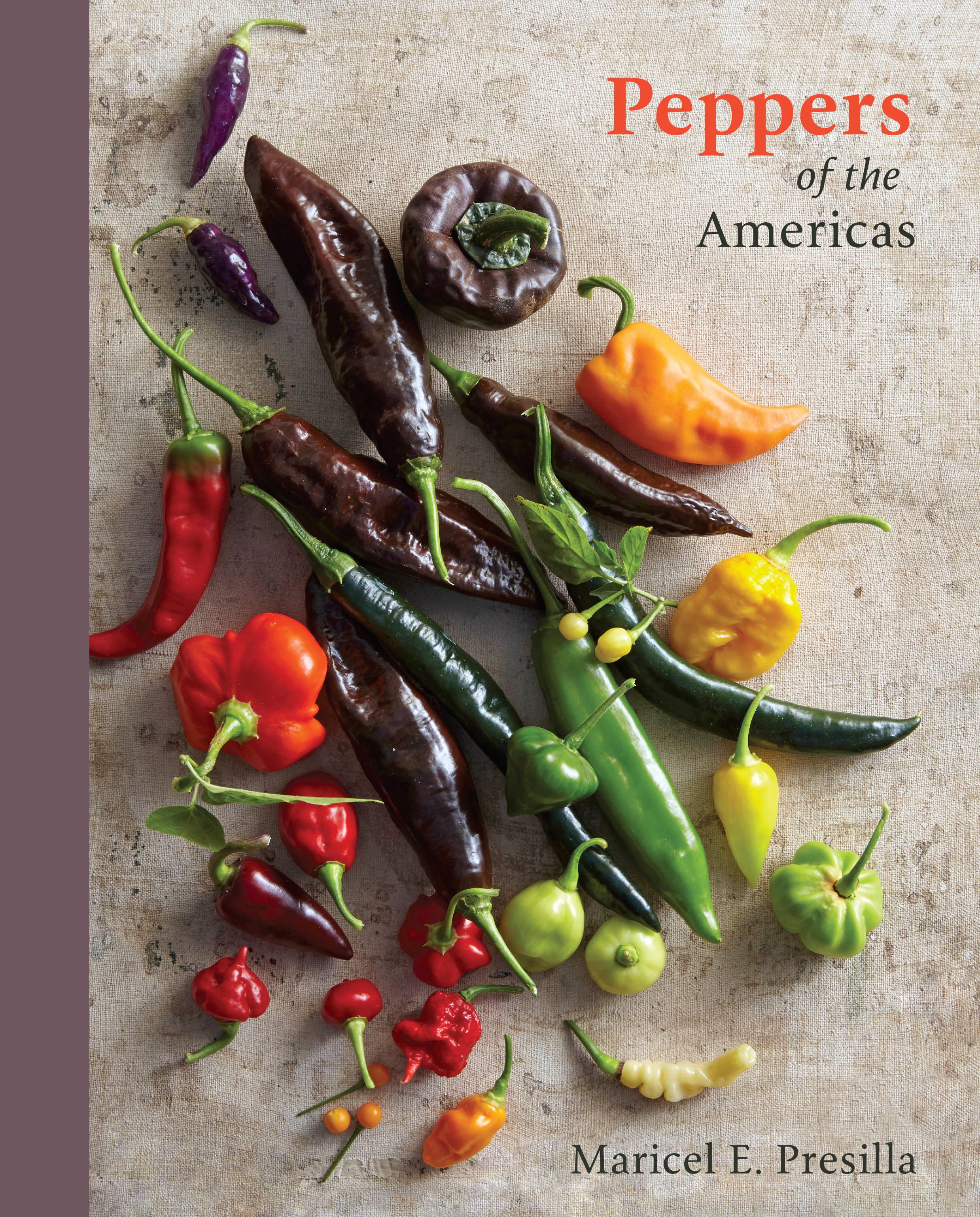

I had come to Weehawken to meet Presilla because of her new book, Peppers of the Americas, a lavishly photographed encyclopedia of the Capsicum genus—that is, the chile. Peppers traces, in depth, the history of this spicy, addictive member of the nightshade family, from its uses in the pre-Columbian Americas (where it originated in the wild) to its spread around the world over the last five centuries.

The book is filled with photos (by Romulo Yanes) and descriptions (both culinary and botanical) of peppers, from ají amarillo (“intensely fruity, flavorful, and colorful”) to the wild Sonoran chiltepín (“clean, bright heat and a grassy edge”). And there are recipes! An Alicante fish paella. A shrimp ceviche with yuca. Sichuan-style “tiger” peppers, dry-fried and doused in soy sauce and Chinkiang vinegar. I wondered: How did a woman born in Cuba—a land not necessarily famous for the spiciness of its food—get so obsessed?

As we sat in her living room—surrounded by her father’s paintings (of cacao pods, among other subjects) and occasionally interrupted by her three parrots and her eight-year-old twin goddaughters—Presilla filled me in on Cuba’s centrality to the story of peppers.

“In Cuba, we understand very flavorful peppers,” she explains, citing the cachucha, a Capsicum chinense. “Same incredible aroma and flavor of the habanero—it’s the same species—but it’s sweet. It can be a bit hot, but not that much. It’s extremely flavorful. It goes into many soups, into black beans.”

But it’s not Cuba’s only pepper. There is also, she said, the ají guaguao (pronounced wow-wow), a “very hot” pepper used by the Arawaks, the island’s native population, that now “grows wild by the side of the roads.”

“My father liked that—my mother did not, and most people in my family did not,” Presilla says. Her father used ají guaguao in enchilado de camarones and in chilindron de chivo, and because he liked it, it became Presilla’s “first taste of hot peppers.”

That first taste didn’t lead immediately to obsession. She continued to eat peppers, of course, after her family fled to Miami in the 1970s, and when she studied medieval history in Valladolid, Spain, and when she got her PhD from NYU, and when she taught at Rutgers, and when, in 2000, after years of cooking for friends and family, she opened her first restaurant, Zafra. No, the mania began when she started researching Gran Cocina Latina, an effort that took her to every country in Latin America and taught her that “everywhere you go, you find peppers.”

Maricel Presilla’s backyard in Weehawken, New Jersey.

They were in the Caribbean, where the focus was on fresh chiles—“the counterpoint of sweet with a hint of hot.” There were even more in countries with strong indigenous cultures, like Mexico and Guatemala , where hot peppers are often dried and used in cooking sauces or turned into table sauces “that add the jolt of heat that people need.” In Peru, Presilla tasted the rocoto of the highlands and ají panca of the coast, and in the Amazon basin she tasted the “hundreds of cultivars that people use daily.”

As Presilla talked about peppers—and as we moved from her living room to her backyard, occupied almost entirely by hundreds of pepper plants growing in large pots—she talked not only about flavors, uses, and obscure varietals (such as the Earbob, which “tastes like a hog plum”) but about historical and cultural connections—about how the celebrated Datil peppers of Saint Augustine, Florida, originated not in Minorca but in Cuba; about how the popularity of habaneros in the Yucatan peninsula demonstrates the close commercial ties between that region and Havana; about how African slaves arriving in the New World were quick to adopt the spicy flavors of indigenous peoples, preserving traditions both culinary and cultural. For Presilla, the key to understanding Latin America is the pepper (and cacao, too, but that’s another story).

But just because she’s obsessed, don’t expect to see her thoughtlessly chowing down on ghost peppers, Carolina Reapers, Trinidad Scorpions, or the other ultra-mega-hot varieties that get so much attention these days.

“We are not chileheads,” she said. “We were born with peppers; we were raised with peppers. It’s not a sport for us.”

What she’s looking for is that ideal but elusive balance of flavor and heat—you definitely want some of the latter, but too much gets in the way of the former. For her, the most interesting are Capsicum chinense, the species that includes the hottest varieties, from the habanero and Scotch bonnet to ghost peppers, Scorpions, and Reapers. “They’re the ones with the most complex flavor profiles,” she says, “but you cannot really enjoy that incredible beauty because they’re too hot.”

Observing pepper anatomy leads to understanding a pepper’s heat levels.

To get the most out of them—that is, their intense fruitiness and floral aromas—Presilla uses a technique she learned in Merida, Mexico, called “dancing the chile”: When you’re making a sauce, you cut a cross in the tip of a habanero and you use the pepper to stir the sauce, without ever fully dropping it in. “You get great flavor and the perfect heat,” she says.

I suspect Presilla always gets great flavor and perfect heat. That, anyway, was my conclusion as we ate our lunch in her backyard garden. The tortilla was the lightest I’d ever eaten, the comforting softness of the potatoes sharpened by the sweet, gentle bite of the poblanos and the tart fire of that fit-inducing Oaxacan salsa. Nothing was overpoweringly hot, yet the spice of the peppers was still enough to call attention to their presence, to spark up a midsummer meal. Surrounding us, as we ate, were Presilla’s babies, vinelike chiltepines and commercial cultivars with names like Mucho Nacho and Holy Mole!

With so many peppers in her life, I wanted to know, did she have a single favorite? If Presilla could have only one for the rest of her life, what would it be? Which chile reigned supreme?

“It’s very hard for me to tell you which is the best pepper,” she says, “because I believe that each pepper has its own beauty, and they have a place in the kitchen.”