In spite of having roots there, this enormously popular Indo-Chinese dish would be difficult to find in Manchuria.

One of the most iconic Indian dishes is made by battering and frying shrimp, cauliflower, or chicken and tossing it with a mix of ginger, soy sauce, and rice wine vinegar. Though it’s almost always labeled “Manchurian” on menus, paradoxically, the dish most certainly would be found in India rather than in China or for that matter Manchuria—modern-day northeastern China. In fact, the dish is so popular in India that even McDonald’s has periodically featured a Manchurian-style burger on its menu.

At the surface, an Indian’s deep love for Chinese food might seem a bit perplexing. For one, there’s isn’t a large population of Chinese immigrants in India (currently there are approximately 7,000 people of Chinese descent, including expatriates, living among 1.3 billion Indians). And though several Chinese restaurants exist in large metropolitan cities like Mumbai and New Delhi, the ones owned by Chinese immigrants are few and far between.

But the reason Indo-Chinese cuisine is so popular is also the reason it tastes so different from the more familiar versions of Chinese food we see in the West. “Indo-Chinese,” or “Hakka,” as it is sometimes called, involves a marriage of texture and flavor brought about by the judicious use of spices. And when it came to Indo-Chinese food, my family was no different: Every Christmas or Easter holiday, my grandmother would make a large batch of Manchurian chicken or sweet and sour shrimp in addition to her traditional staples of rich coconut beef and chicken stews, fresh tomato and cucumber salads, and cardamom scented pilafs. Her somewhat disconnected menu seemed to work with perfect symphony—all being orchestrated through spices.

Though their numbers have significantly and steadily declined over the years, Chinese tradesmen and Buddhist monks have visited India for centuries. The first Chinese immigrant community was established in 1780, when a Chinese man, Yong Atchew, received a grant from the British to start a sugar plantation in Kolkata (or Calcutta, as it was then called). As the business prospered, the influx of immigrants increased, including the Hakka tradesman who specialized in leather tanning and shoemaking. Kolkata is where the first Chinese restaurants cropped up, and it is also the city that houses India’s only Chinatown. Soon restaurants in Kolkata had large, shimmering woks that sat on fiery stoves, filled with countless bowls of Hakka egg noodles tossed with hot Indian green chiles and seasoned with a splash of chile sauce and tomato sauce, chicken fried rice made with long-grain basmati, or the American chop suey, a dish composed of mixed vegetables and chicken in a sweet gravy that’s topped with crispy noodles and a fried egg.

As time went on, these dishes started to adapt to their new surroundings, and the Indian preference for spice and heat made their way through. Dishes like “chile chicken,” Sichuan paneer, and chicken Hakka noodles began to make appearances all over. A combination of spice, heat, and bold flavors helped to quickly endear these dishes to hungry Indians, and the number of restaurants started to grow quickly across the country.

As customers demanded more, chefs got more innovative, and this eventually led to the birth of Manchurian chicken—a dish that, like General Tso’s, is rarely if ever found in China. Manchurian chicken was the brainchild of Nelson Wang, a third-generation Chinese Indian immigrant from Kolkata. According to Nabanita Dutt’s book To North India With Love: A Travel Guide for the Connoisseur, in the early 1970s, the Taj Mahal hotel in Mumbai brought in chefs from the Sichuan province to create spicier versions of Chinese food for their Indian clients. These new dishes took off, and a prudent Wang paid attention to the growing trend when he noticed the customers in his restaurant asking for similar dishes infused with an extra boost of heat and flavor.

But having never visited or lived in China, Wang was unfamiliar with the Sichuan style of cooking and decided to play around with the ingredients he had on hand, keeping in mind his customers’ tastes. He tossed bits of chicken in a thick cornstarch batter, deep-fried the pieces, and served them with a hot gravy made with soy sauce, vinegar, onions, chiles and garlic. Thus, Manchurian chicken came into existence and it quickly became one of the most popular dishes of Indo-Chinese cuisine. Wang eventually expanded his restaurant business and opened the famous China Garden restaurant in Bombay, where you’ll see photographs of celebrities from both Hollywood and Bollywood (there’s a photo of a denim-clad Goldie Hawn from the early ’90s) hung on the walls.

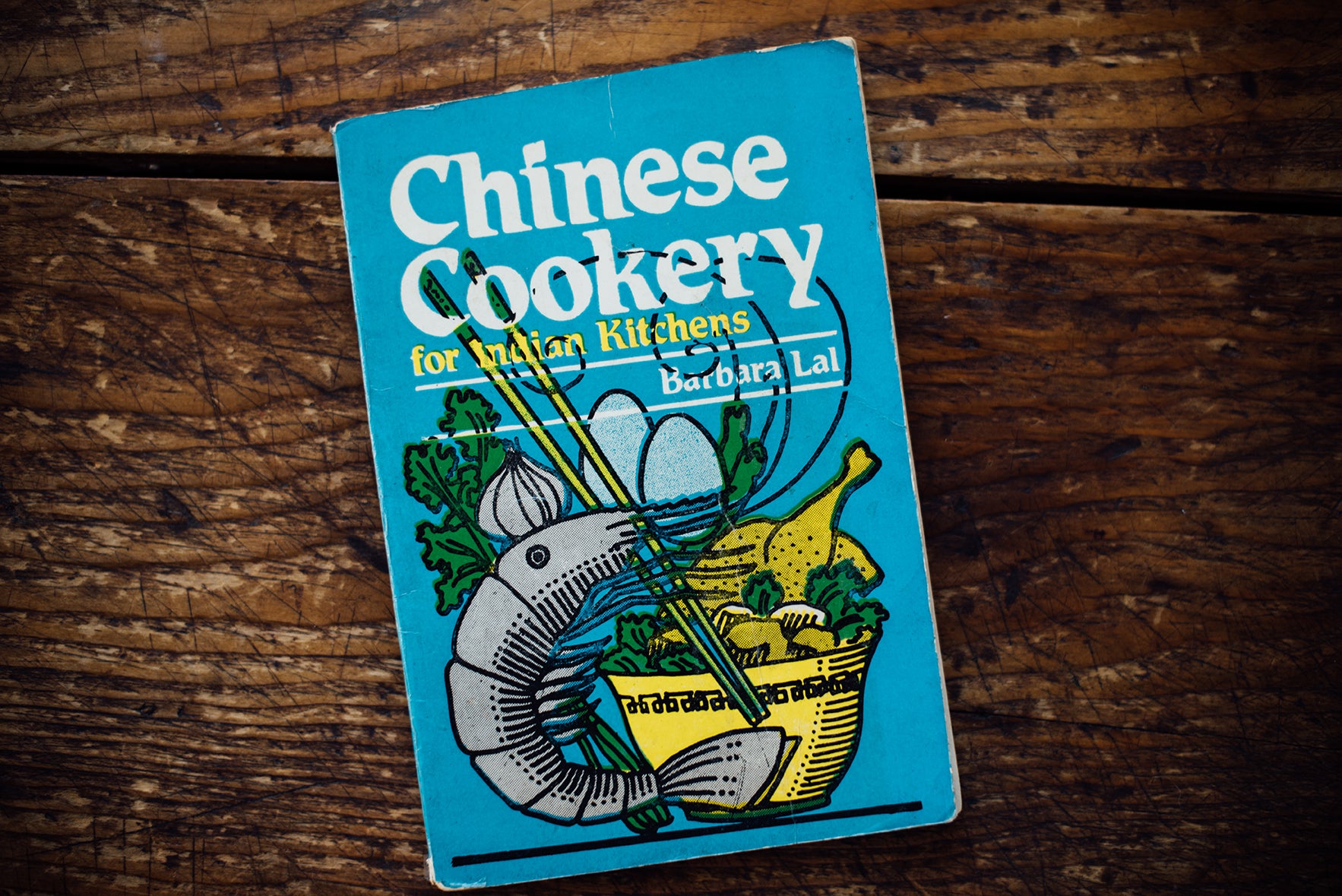

Today, Indo-Chinese food is an inseparable part of Indian culture, and it’s practically impossible to find these unique dishes outside India or in cities where there’s a sizable Indian population, like New York, or in countries like Singapore and Malaysia. There aren’t too many cookbooks on the subject. I own my mom’s copy of Barbara Lal’s Chinese Cookery for Indian Kitchens and a few other cookbooks on Bengali cooking from Kolkata that have a few recipes included. With a couple of ingredients, you can bring this unique cuisine into your kitchen with a recipe like this Manchurian cauliflower, which only requires a bit of rice to go along with it.