They may be only Band-Aids for the region’s food insecurity, but “blessings boxes” are popping up in more and more parts of Appalachia, dutifully refilled by local pastors, police officers, and anyone with a box of pasta to spare.

At first glance, you might miss the Pikeville Church of God: a low-slung building that’s nestled into the crook of a curvy eastern Kentucky road so snugly it could almost be mistaken for a natural part of the topography. I certainly almost rolled right past the first time I visited—until I noticed an older man, box of dry pasta tucked under his arm, trudging away from the church along the sludgy shoulder of the highway.

“Come in, come in!” Reverend Sandra Layne beckoned as she unlocked the front door of the church and ushered me inside her wood-paneled, one-room sanctuary from out of a fog-dense September drizzle. A lifelong resident of Pikeville, Reverend Layne is unique among pastors in the region not only because she’s a woman, but because she’s an African-American woman leading a congregation in a town that’s 92 percent white. Layne began preaching after her husband, the former pastor, passed away in 2014; she built the blessings box last year as a tribute to his memory. “We’re certainly not the biggest of the blessings boxes here in Pike County—but I do know we serve the most people,” she told me.

A blessings box at Clearfield Baptist Church in Clearfield, Kentucky

“I wanted to find a way to honor my husband and his commitment to the service of others,” she said, a soft, affectionate smile spreading across her face. “He really was my honey. Now that little idea—whew, that blessings box—is the most used one in the whole area.”

Blessings boxes are homemade, often standalone, cupboard-like structures placed in high-traffic (mostly pedestrian) locations and filled with nonperishable food items that are free for the taking by those in need. Driving down the Tom T. Hall Memorial Highway in Carter County (named after the legendary “Watermelon Wine” country singer), it’s easy to track down a recently sprouted blessings box, whether you swerve onto the switchbacks that head toward Rowan County or simply stroll through downtown Grayson. Primarily located near churches, recreation centers, or civic buildings, these volunteer-built, volunteer-stocked public resources have twined their way into the fabric of rural communities across the country over the past few years and become charitable fixtures throughout Appalachia.

McClard saw the boxes as a “potential gap filler” for the food insecure who weren’t being adequately served through other means, like food banks and shelters.

The first blessings box—or Little Free Pantry, as they’re also known—was founded in Fayetteville, Arkansas, by Jessica McClard in 2016, who was inspired by the Little Free Library movement. McClard saw the boxes as a “potential gap filler” for the food insecure who weren’t being adequately served through other means, like food banks and shelters. “I saw the [Little Free Pantries] as a way to help people immediately who were between checks or had just moved,” she explains. “I wanted to find a way to help feed as many people as possible, as quickly as possible.” Today, the Little Free Pantry website pinpoints roughly 350 pantries on an interactive map, but McClard believes the majority of boxes are uncounted and estimates there are likely over 1,000 pantries worldwide.

A blessings Box at Olive Hill First Christian Church in Olive Hill, Kentucky

While there’s no exact count on the number currently dotting Main Streets across Appalachia, ask anyone who operates one and they’ll tell you: The demand far surpasses the resources. “Our box gets filled up about three times each day. Every morning around 6:30, the police department goes to all seven of the blessings boxes in Pike County and stocks them [with supplies they’ve gathered]; then at lunchtime, some of the sisters from our congregation who are coupon clippers come to fill our box; then after we leave here this afternoon I’ll stock it again. We can’t ever keep it full. I always tell people, ‘If you want to get rid of something, put it in a blessings box and watch it get gone.’” She was right: When I looked outside as I left, there was nothing in the box but packages of plastic utensils.

Hunger runs rampant across Appalachia—particularly for women, children, and those with housing instability. In eastern Kentucky, where I’m from, 25.4 percent of people live at or below the poverty line, as compared to 18.9 percent of residents in the rest of the state and 15.6 percent of people nationally. During the 2015–2016 school year, 27,000 high school students in the region experienced homelessness at some point, compounding food-insecurity issues for the region’s youth.

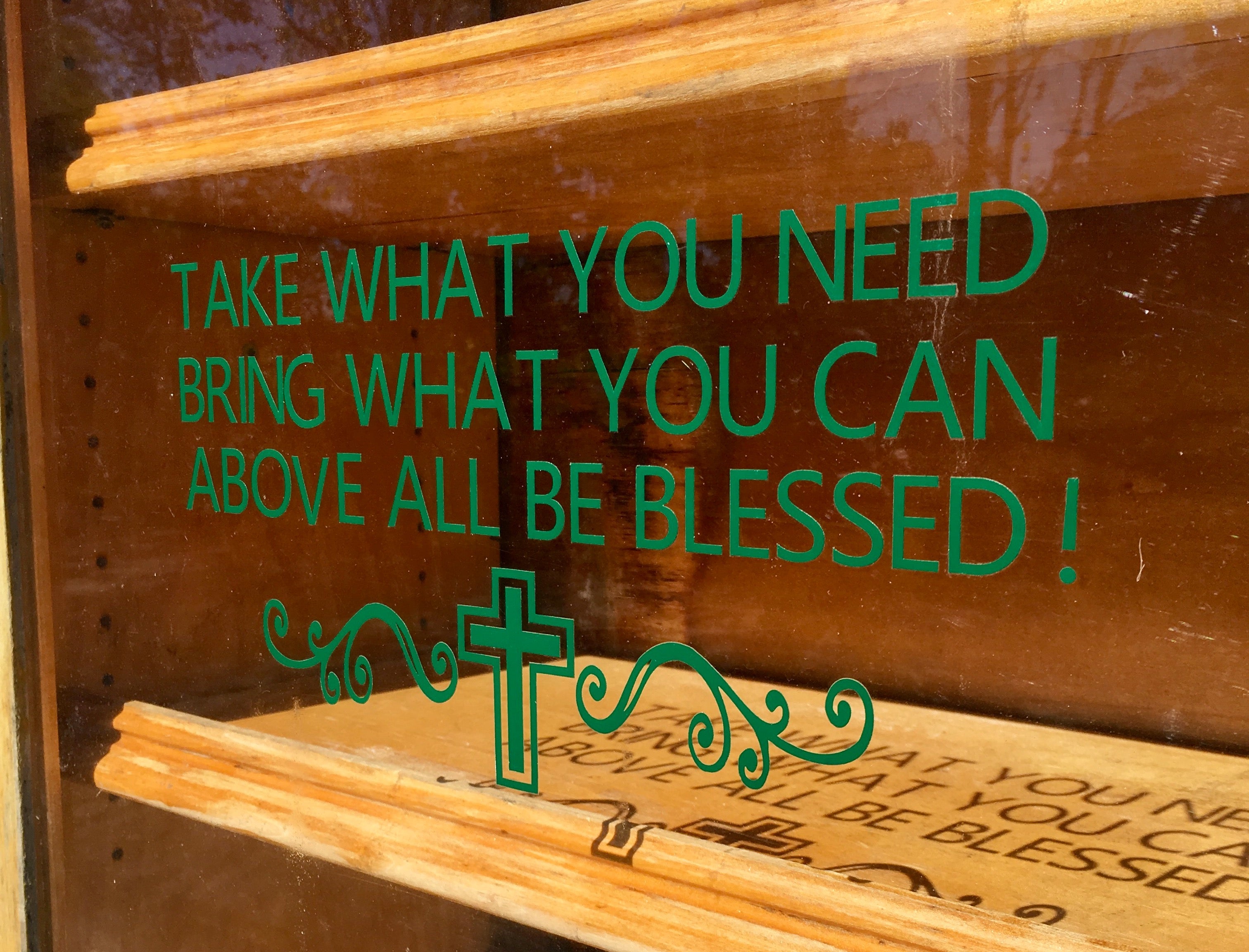

The meager contents of a blessings box in Morehead, Kentucky

“Hunger is a very real thing here, particularly among children,” says Jessica Mansfield, Director of Children’s Ministries at the Morehead United Methodist Church in Morehead, Kentucky. “So if a little kid or a teenager keeps going home to no food in the pantry, they can see that there’s something there for them in the blessings box that’s quick and easy. They can grab a can of tuna and eat it or flop some soup into a bowl and warm it up. Spaghetti has been a popular item because it’s easy to prepare for kids who are without much help. It’s not because families don’t care; it’s because there are limited resources here, and when you add a generation [of parents] in jail for drugs, it just causes a higher level of hunger.”

“There’s a culture of shame in America: People feel like if they’re poor, they aren’t working hard enough. But we know that isn’t true. The blessings boxes help to keep them from shame.”

Those who operate the ever-mushrooming number of blessings boxes are quick to point out how these mini-pantries—with their 24/7 accessibility and lack of requirements (like a driver’s license or proof of county residency) for getting meals—are picking up the slack where larger food pantries fall short.

“Our church started helping out a local pantry before we built our [blessings] box, and people would remind us that the pantry was only open on Tuesdays and they couldn’t wait until the next week to get food—they were hungry then,” says pastor Jason Johnson of the Prestonsburg Church of God in Prestonsburg, Kentucky. “The problem with food pantries is that most of them say, ‘OK, you can come get this and this, but only if you meet this set of criteria.’ With blessings boxes, you don’t have to give your name or Social Security number or anything like that. People can be discreet. There’s a culture of shame in America: People feel like if they’re poor, they aren’t working hard enough. But we know that isn’t true. The blessings boxes help to keep them from shame.”

Mansfield agrees. “Privacy is an important part of the [blessings box] because I want people to not feel shy about taking help. There’s a sense of dignity that people need to have. We built our blessings box in the back of a parking lot, so people don’t have to worry [about] ‘Who’s going to see me take food?’ They can just get the help they need.”

Reverend Sandra Layne, with a three-day supply of food to fill her blessings box

The first time I encountered a blessings box was last year in Paintsville, Kentucky, where I watched as—almost every other day—the simple, two-tiered wooden chest was visited by a seven-year-old boy who looked a little like the freckle-faced kid from The Sandlot. The boy, who I started calling Baby Thor due to his propensity for dragging around a large hammer at all times (yes, really), would completely empty out the box on each visit—all contents stuffed into a pillowcase—before heading home. I often wondered if he was sent there by an older family member who might’ve been embarrassed to be seen making use of such a prominently displayed symbol of need.

It’s easy to view blessings boxes as generous acts of community outreach because, of course, they are. Who on earth could hear Reverend Layne’s stories about the near-constant stream of those in need looking for a can of ravioli or loaf of bread and not believe that these boxes are serving a necessary, benevolent purpose?

From another perspective, the boxes are highly visible, public symbols of the food insecurity that’s plagued the region for generations—and only continues to worsen. Like a GoFundMe page for a schoolteacher who can’t afford cancer treatments, or a YouGive campaign for a line cook who’s been hit by a car and can’t return to work, there’s something glaringly wrong about the fact that we’ve come to accept that the system is so broken, on so many different levels, that there are wide swaths of our communities for whom hunger has become a foregone conclusion. Witnessing and working to fix the immediate needs of those in food deserts is one thing, but it’s perhaps even more important to talk about what led us to this point—and how we can begin to move the dial on large-scale, systemic changes that will address the root causes of hunger in the area.

For now, though, there’s an immediate need to address each day, and leaders like Reverend Layne aren’t showing any signs of slowing. “I’ve seen adults eating baby food out of our box, and it’s enough to break your heart,” she says, pausing to shut her eyes. “But you know what? People using the box never cease to say thank you. Every person I see out there—they’re always full of thanks.”