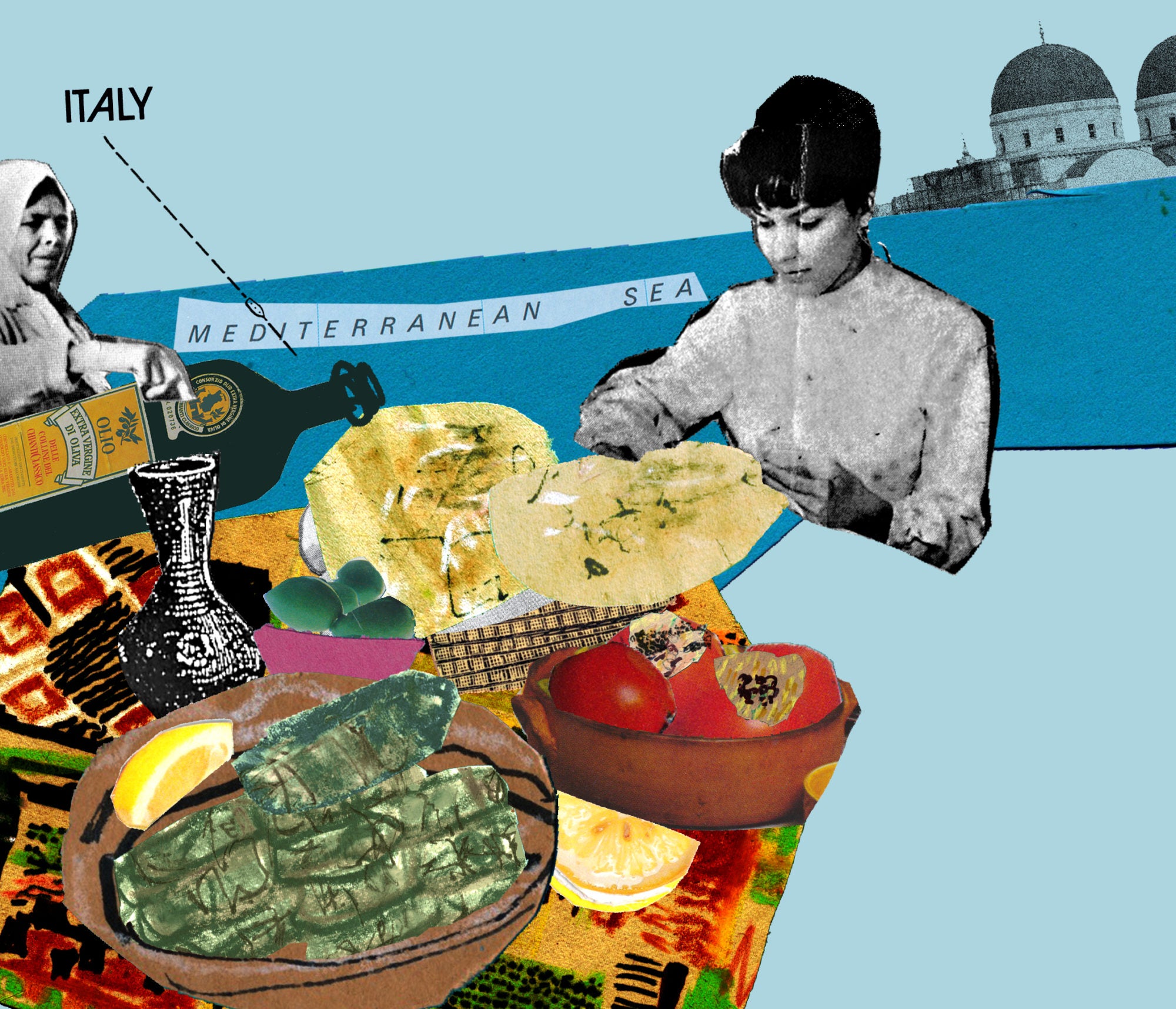

Growing up in Libya in the early 1980s, Reema Islam found—and fell in love with—traditional cuisine that bore the influence of four decades of Italian rule.

I was born in Benghazi, Libya, to a family of Bangladeshi and Pakistani descent. My childhood was spent by the shores of the Mediterranean, swinging from the olive trees and mixing up Arabic words with the Urdu and Bangla we spoke at home. Our dinner table was likewise a mesh of flavors, as my parents loved blending their own native cuisines with the Italian, Libyan, and Mediterranean tastes we were exposed to.

Libya borders the Mediterranean but is also home to a large expanse of the Sahara desert, where the Bedouin and Amazigh communities add to the culinary blend of cultures. Traditional Libyan food includes rustic, bread-based dishes like asida, a steamed dough dumpling surrounded by butter, and bazin, a similar dish in which a steamed or baked mound of unleavened bread sits in a meaty broth. But both Libya’s food and vernacular carry a lot of Italian influences, a legacy of Italy’s colonization of the country between 1910 and 1947. When my mother arrived from Pakistan in the mid-1960s to work in the medical sector, she picked up Italian words like bambino, thinking it was an Arabic dialect.

In Benghazi, my parents adjusted to the taste of olive oil in their food, while the use of cumin offered a sense of familiarity in an alien world. My mother’s colleagues taught her how to roll grape, cabbage, or spinach leaves into abrak (or dolmades), and to make mahshi (also known as gemista), or peppers, aubergines, and zucchini stuffed with fragrant rice and steamed.

During picnics with our Libyan friends, which were set against the red-hued mountains and smoky smells of barbecued meat, sheep intestines were cleaned and then stuffed with rice mixed with fragrant spices, parsley, and raw meat. The resulting dish, called osban, was cooked in a steamer over a wood fire, and I remember using all the strength of my young teeth to battle with the cooked innards’ elastic texture as rice spilled onto my plate. It taught me, early on, that all good things come with a bit of effort.

My desire to explore more local flavors often led me, on the slightest pretext, across the hallway to the apartment of our neighbor, who cooked rice with huge chunks of meat and at least three times the amount of tomato paste and chiles my mother used. My neighbor’s family ate together out of a large bowl, digging in with their spoons and trying to save the bigger pieces of meat for me as I struggled between mouthfuls, wiping my streaming eyes and nose.

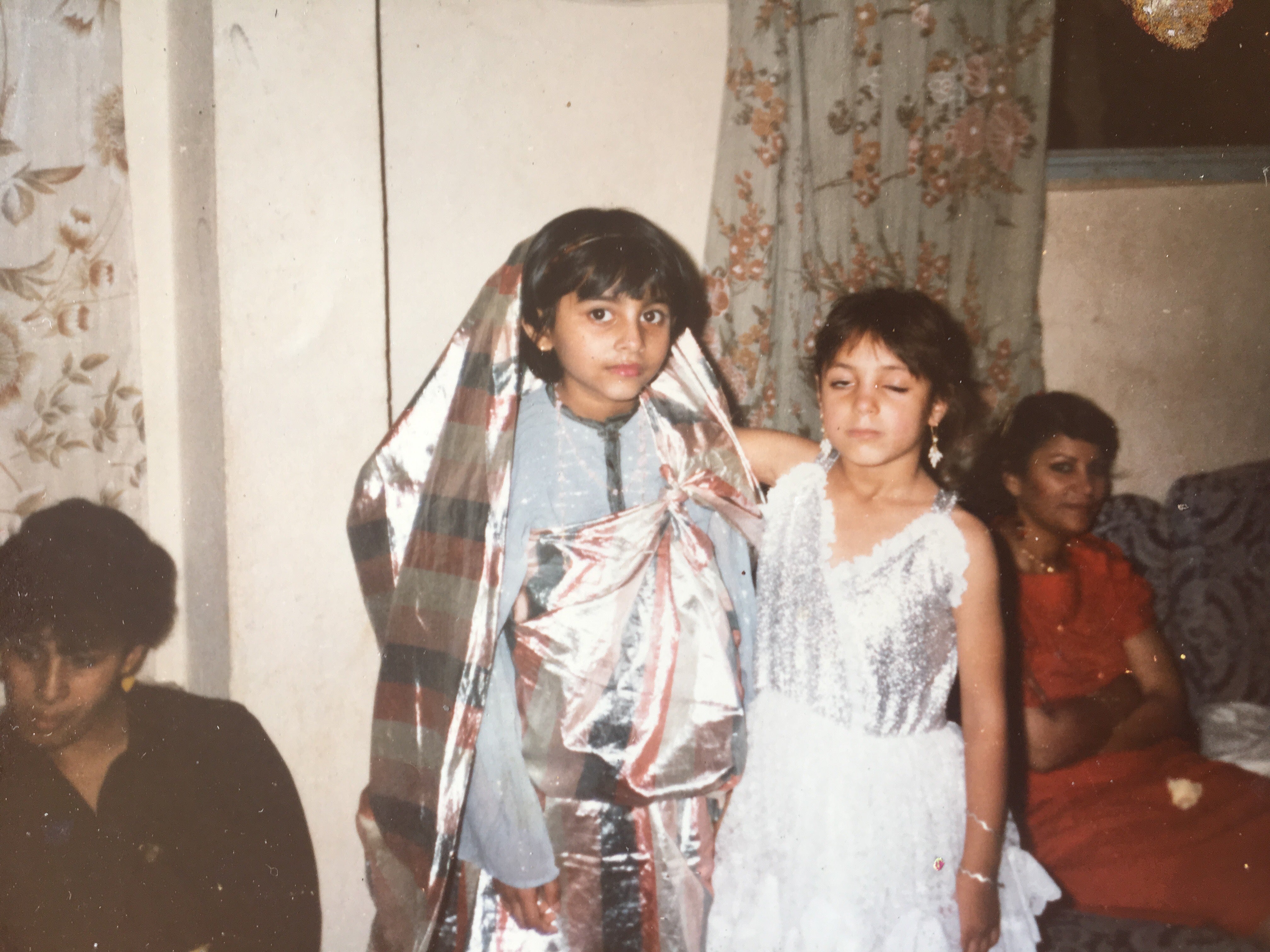

The author, left, and a friend at a wedding in Benghazi at age 6

Another Libyan staple, the macaroona, was similarly cooked with gigantic portions of meat and enough tomato paste to ensure a combination of pure delight and severe acidity. In my family, macaroona was eaten on Friday, or the holy day that began the weekend; our version featured elbow macaroni with toned-down amounts of tomato paste, bite-size pieces of meat, a strong touch of celery, and an additional sprinkle of oregano powder or za’atar. My mother served it on individual plates, even though I always wished we could eat the Libyan way, meaning out of one cavernous bowl with either bare hands or spoons, depending on the formality of the setting.

Another favorite was khubz, the leavened flatbread that in Libya is eaten with almost everything, from a bit of olive oil mixed with za’atar to the multipurpose salad known as sharmoula. In sharmoula, cucumbers, tomatoes, peppers, and lettuce are mixed with loads of olive oil and lemon juice; it was the perfect entrée for those days when the hot Saharan winds parched us. This was perhaps another one of those Italian-influenced salads that had adapted well in a country where the red dust storms called ghiblee would convert the landscape into a scene from Mars. Sharmoula remains an indispensable part of our dinner table to this day, but the howling sound and reddish skies of the ghiblee are perhaps my least favorite childhood memory.

A much happier one comes from the days when my two older siblings attended their scouting classes; on the way home, my father always treated us to something. We would sip gazooza, or fizzy drinks, and munch on semolina cakes topped with almonds and biscuits, the latter of which smelled intensely of bakhoor, an incense that was smoked on the coals next to them.

But my fondest memory of all is an act of rebellion I staged with my siblings. My mother was forever feeding us healthy meals and strictly discouraged us from trying the local street food, so my sister found ways to sneak in snacks from the roadside stalls near her school. The most quintessential of them was the sandawish, or wrap, made from khubz, slathered on the inside with olive oil and a generous smearing of hareesa, or red chile paste, and stuffed with lots of fresh lettuce, za’atar, and olives. I still can’t decide whether it was the thrill of eating forbidden food or the burst of flavors that continues to make the sandawish one of the high points of my childhood.

I was seven when we moved back to Bangladesh, but even after we returned, Libyan food remained such an integral part of our lives that my mother continued the tradition of cooking it on Fridays. Sourcing her ingredients here was so much harder, and that difficulty led me to one of my most shocking childhood discoveries: that macaroni—along with all other pasta dishes—was actually Italian food and not traditional Libyan cuisine! I was also surprised to learn that khubz wasn’t the name for all kinds of breads, but I kept calling them khubz anyway, much to everyone’s exasperation.

Today, no one misses dinner at my mom’s on the day “Libyan rice” is cooked, no matter that the rice mix used to stuff mahshi is often cooked on its own and the store-bought olive oil makes it taste different. I recently lived in Crete for a year, and one day the skies turned red as some dust blew over from the Sahara, across the Libyan Sea. But this time, it felt like an old friend had come for a visit.