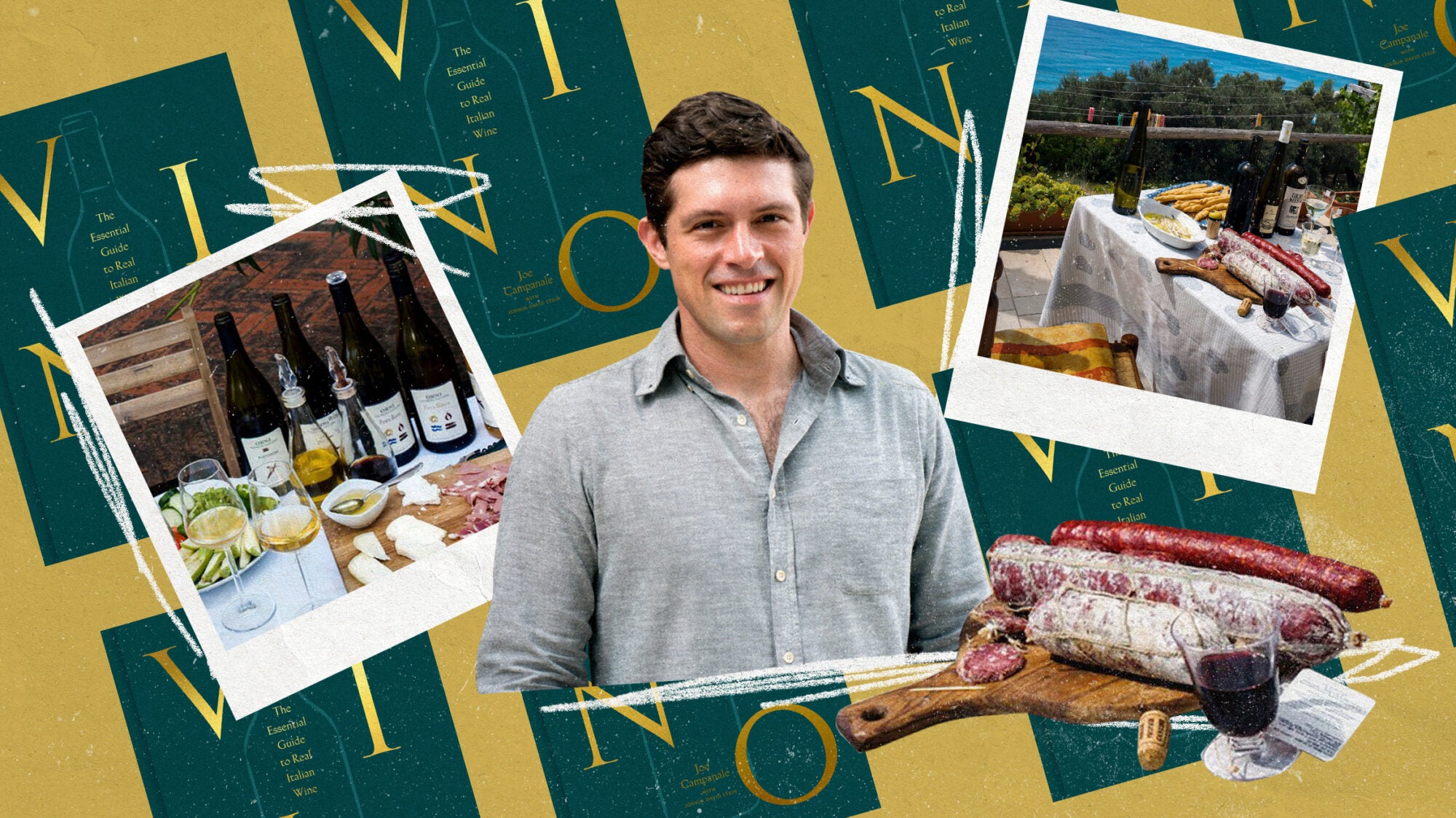

In a new book, Vino: The Essential Guide to Real Italian Wine, a wine expert goes deep.

It’s not hard to puzzle out the professional passions of the wine expert Joe Campanale. A past Food & Wine sommelier of the year and a certified guy to know in New York’s deep bench of wine experts, Campanale is the owner of two wine-focused Italian restaurants (Fausto and LaLou) and cofounded three others, most of them focused on natural winemaking. The Queens native also heads the wine label Annona, focused on producing organic and natural wines from the center and south of Italy.

So it’s probably no great surprise that his first book on wine is called Vino: The Essential Guide to Real Italian Wine—“real wine,” or “vero vino” in Italian, being a term he picked up from a genial Italian wine store owner during an undergraduate study abroad session in Florence. What is surprising is how genuinely unjaded, in fact genuinely excited, Campanale remains about the topic and about Italy, which, he told me in recent phone call, is just now coming into its own as a maker of these real wines. We spoke about the three things that make a wine “real,” and I got some great advice for visiting a winery that makes real wine in Italy—which, of course, Campanale suggests everybody should do at least once in their life.

What three things make a wine “real”?

I’ve been thinking about the concepts behind it for a long time, especially with the conversation around the natural wine movement, which to me is sort of an oversimplification of what really good wine should be. All the wines that I love start first and foremost as wines that are made organically or biodynamically, without any chemicals at all and as hands-off as possible. But saying that in and of itself, to me, isn’t enough—it’s just the baseline. Saying a wine is a natural wine doesn’t inherently make it a good wine. Beyond that, it has to be made from the right grapes. In Italy, the right grapes are the indigenous grapes, because Italy has more of those than anywhere else.

Oh, that’s cool.

You can drink a Chardonnay or Syrah from anywhere in the world, and so many of them are really tasty, but I’m always looking for what makes the wine unique—and the story behind that and the local flavors. Then you also need a talented winemaker who knows what they’re doing. Anyone can throw grapes into a barrel without sulfur, but that doesn’t mean the result is necessarily going to be good. That very low-touch or most natural way of making wine requires even more skill, to be more hands-off, if that makes sense.

Is this common in Italy now, to think about evaluating wine in this way?

I’ve noticed in the last ten years that there’s been such a sea change, with Italians feeling a lot more pride in their local grapes. When I first started in the wine industry, a lot of producers would make a local wine and it wouldn’t be very expensive—and the local wine would be indigenous grapes or a traditional-style wine. Then their expensive wine would be like 50 percent Cabernet and 50 percent local grapes, aged for two years in new French Oak barrels. Now you’re seeing producers move away from that. They’re not using as much French Oak. When you have new French Oak barrels, you start to taste the oak a lot, and to me, that covers up the flavor of the wine. They’re moving away from using the French grapes, and especially from using them for their top wine. I really love seeing when a producer might have a really fancy wine, but it’s all from an indigenous grape. And you’re seeing that more and more.

Part of your book is like a fantastic travel guide to the wineries of your favorite makers. I feel like people are going to rent a car, drive up to all these winemakers’ houses, and knock on their doors. Would that be okay?

I’d say that, in general in Italy, they really appreciate you making an appointment. There are very few producers that are set up that way, like in California, where you might be able to just stop by during tasting room hours—especially the producers who you want to go visit. They appreciate an appointment because, often, these wineries are family businesses. Oftentimes, if you’re going to go do a tasting there, you’re actually visiting their house, where they live and work.

I’m curious what you think it is about wine that makes learning about the point of origin so impactful, so helpful?

I think wine is special in that way. When it comes to the wines in the book, those artisan wines that are made with a light touch really start to taste like and smell like the places that they come from. Just the other night, I drank Fonterenza, which is a producer in Montalcino. The Rosso di Montalcino reminded me of the smell of the air in Montalcino, the herbs that grow in the ground there, the kind of underbrush, and the dirt.

I think that’s something that wine has a better way of translating than pretty much any other food product. Also, because the places that wine come from are pretty great, you want to go there. Good wines aren’t really made in ugly places, and I think being able to be transported to these absolutely beautiful, lovely places through your glass is a great experience.

Three Italian Wineries to Visit from Vino: The Essential Guide to Real Italian Wine:

- Podere Le Boncie, Tuscany

Giovanna Morganti made the first real wine Joe Campanale ever tasted, a Chianti Classico called Le Trame. - Giulia Negri, Piedmont

“Barologirl” Giulia Negri makes artisanal, delicate Barolos with floral tones and minerality. - Nusserhof, Trentino-Alto Adige

Heinrich Mayr and his daughter Gloria grow native grapes in the center of the Alpine and Austro-Italian town of Bolzano.