Jiggly, melt-in-your-mouth soft and silken tofu has (finally) come of age stateside.

A cream-colored tangle of curds, loosely congealed like a cumulus cloud and submerged in a clear liquid, arrives at the table unannounced. The petite porcelain bowl is the compulsory amuse-bouche at DubuHaus, a Korean restaurant in Midtown Manhattan devoted to tofu, or dubu, as the Korean language commands. There diners can casually watch tofu being made through a glass panel looking into the workstation, where, twice a day, soybeans are pressed into milk that is coagulated into tofu and served warm in seafood stews or spicy pork belly braises before ever seeing the inside of a refrigerator.

Why? Because the proteins in the tofu will firm up when cold, says the restaurant’s dubu specialist, Kyle Kim, ruining its pristine pillowiness. “Fresh tofu is juicy and soft, a better texture—you cannot compare it to tofu from the refrigerator,” he explains.

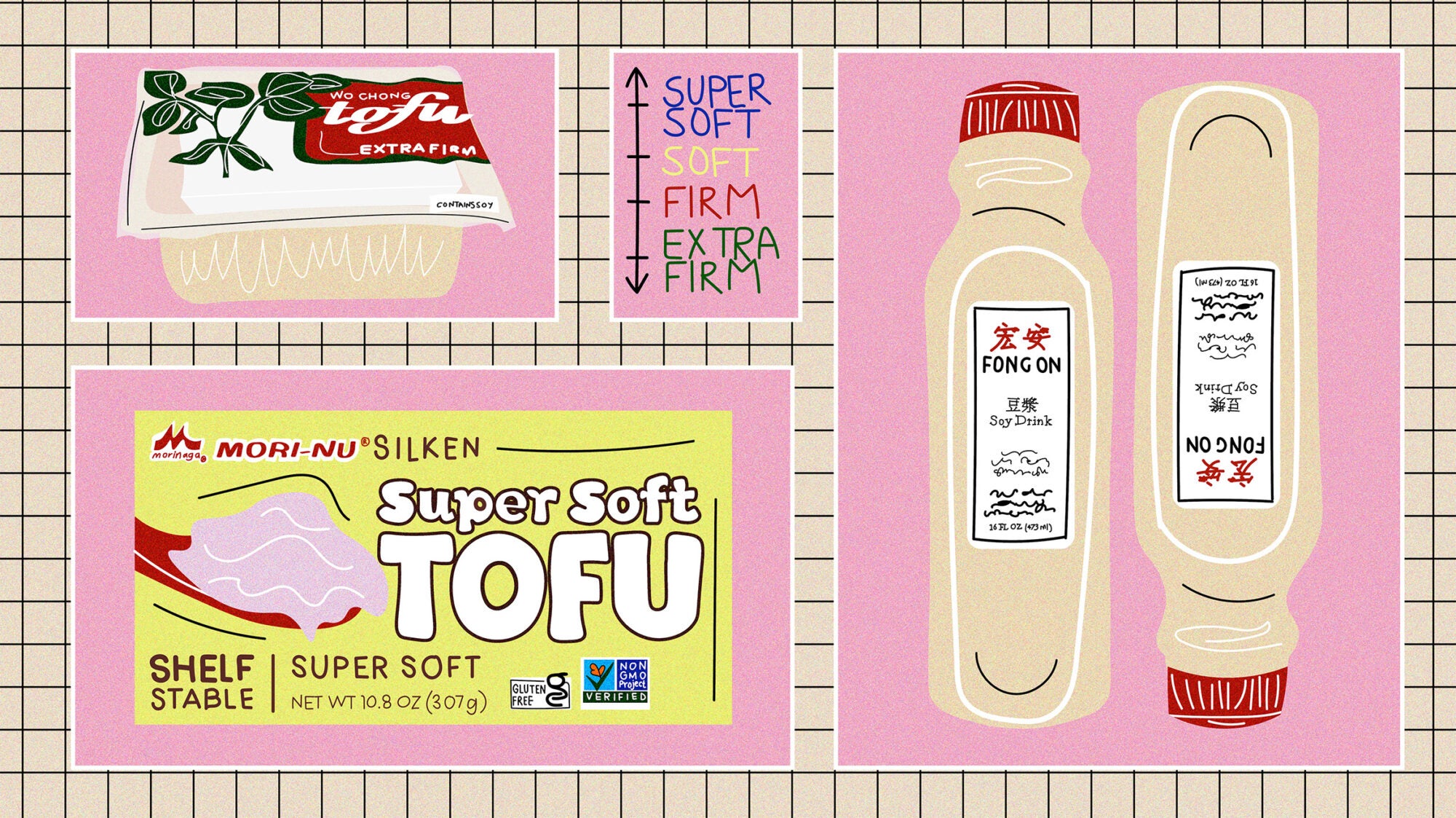

Soft, juicy. Tofu is one of those staple foods that can shapeshift in so many ways it might seem strange to lump all its manifestations in the same category (much like chihuahuas and huskies are both, incredibly, dogs). Roll through an H Mart or a Chinatown supermarket, and you’ll find a colorful assortment of blocks, tubes, knots, skins, and noodles of bean curd, for instance.

By contrast, my local supermarket in Manhattan only sells two of them: firm and extra-firm. These may be the platonic ideal of tofu in America: pressed to a meaty denseness that you can chew on, and the finished product is often subjected to searing, roasting, frying, marinating, tossing, and heavily saucing in a quest to make it a suitable meat replacement—rather than showcasing its virtues in a more pure state.

In recent years, a number of articles from US-based food outlets have presented a hack involving freezing then thawing firm tofu, a process that results in a “pleasantly spongy interior” (the New York Times) and “meat-like consistency” (Bon Appétit) that’s “fitting for a faux McRib” (Eater). There is a time and place for all kinds of tofu textures, but save for in mapo tofu, the fiery Sichuan dish that’s gained a cultlike fame around the world, softer ones haven’t been as popular stateside.

Now, thanks to East Asian tofu makers and restaurants across the country, an appreciation for soft tofu varieties may be solidifying—and finding its way into supermarkets. From savory-topped tofu puddings offered at a century-old Chinese American tofu shop in New York City to almond-flavored silken tofu from a Japanese American manufacturer based in Southern California, soft, creamy tofu that melts in your mouth is finding more fans. And they’re not just blending it into smoothies for a hidden boost of #protein.

Tedman Louie has always preferred soft tofu to firm, but the latter is what his family’s brand, Wo Chong, sells more of by far. “The question I always get is, ‘Can we make it firmer?’,” he says.

This consumer preference reflects a gradual change in customer demographics since Louie’s great-grandfather started the business in San Francisco’s Chinatown in 1928 to serve the local community. Today it’s the oldest continually operating family-owned tofu brand in America, sold in retail markets throughout Northern California including Safeway and Kroger. Louie says that while Wo Chong has grown considerably over the decades, it’s still a small business in comparison to nationwide tofu brands such as House Foods. Compared to many bigger brands, Wo Chong’s tofu—which comes in soft, silken, firm, and extra-firm varieties—is a lot yellower in complexion because Wo Chong doesn’t dilute its soy milk, he says.

There’s still a lot of love for Wo Chong’s soft and silken tofu from Asian markets and restaurants, says Louie—San Francisco’s Chinese American fast-casual restaurant Mamahuhu uses it for its mapo tofu, for example. But for now, there’s still a clear preference for firm styles of tofu among the non-Asian wholesale and retail customers the company serves.

“I think the American markets think of tofu like a flavorless cheese, so they like that texture with a bite,” says Louie. What’s more, he adds, softer tofu requires more patience and skill to cook and handle it gently, so that the pieces don’t crumble. Cooking it may not be for everyone. But the payoff is worth it, he says—Louie’s favorite way to enjoy soft or silken tofu is by deep-frying it, resulting in a dramatic contrast of textures as its golden crust gives way to an oozing, creamy center so tender it nearly melts in your mouth.

There’s something magical about the interplay of textures and flavors when using soft tofu, says Hooni Kim, chef-owner of Meju and Danji in New York City. Soft tofu, often freshly made, is the main attraction of soondubu jjigae, the eponymous Korean stew that can include pork, mushrooms, and other supporting ingredients. An especially popular version is the spicy seafood soondubu jjigae, where scoops of tofu bob alongside whole shrimp, clams, and bits of squid in a bright vermilion broth. There, as with mapo tofu, soft tofu provides some relief for one’s palate from the onslaught of chiles and strong flavors, says Kim. “I think soft tofu balances things out a bit, so it’s like a soft pillow on a hard bed,” he says.

Ever since the Michelin-starred Danji opened 15 years ago, he has served a crispy fried soft tofu there, and it’s still a bestseller. Cubes of soft tofu are coated in potato starch before being flash-fried, which gives them a sort of “mochi-gooey texture” on the outside, then they are served in a ginger-scallion vinaigrette. It’s very simple, and it’s all about the tofu, says Kim, adding that the dish has won over many diners who previously thought they didn’t like tofu. “Our servers say, ‘If you don’t like it, you don’t pay for it,’ and we’ve never had someone ask for their money back,” says Kim.

What separates soft and firm tofu styles is water content: the more watery or less pressed the tofu blocks are, the softer they are. There are no trade regulations for the categories of soft, medium, firm, or extra-firm, and each manufacturer has its own barometer. So it’s often the case that one brand’s “extra-firm” is firmer than another’s.

Then there’s silken tofu, which undergoes a slightly different preparation process than block tofu. All tofu starts with fresh soy milk that’s heated and coagulated into curds with a firming agent such as calcium sulfate (gypsum) or magnesium chloride (nigari). With silken tofu, the heated soy milk and coagulant are poured into a container to set, rather than allowing the curds to separate from the whey and then forming them into blocks. This results in a uniformly smooth piece of tofu. And within the category of silken tofu, textures can range from a barely set, custardy softness to a jiggly, gelatinlike firmness.

Silken tofu is the predominant style enjoyed in Japan, and its texture can also depend on how the soy milk is made before being solidified into tofu. “Back in the old times, when my great-grandparents made tofu at home, they would use a piece of silk to filter the soy milk,” says Colleen Sherfey, head of marketing at Morinaga Nutritional Foods, which manufactures the Mori-Nu brand of silken tofu. This, she says, helps ensure a smoother, silkier texture in the resulting tofu compared with using cotton cheesecloth.

Mori-Nu was launched in 1985 in the United States as a subsidiary of Morinaga Milk Industry, a Japanese milk and confectionery company. In the 1980s, says Sherfey, as the food industry was growing rapidly with global conglomerates like PepsiCo, Morinaga determined that it couldn’t compete with long-established brands of milk products in the United States. So instead the company decided to bring one of the most common Japanese foods, tofu, to its new market in a distinctly Japanese style: silken. Mori-Nu’s innovation was setting the silken tofu directly in its packaging, a coated cardboard box made by the Swedish company Tetra Pak. Thanks to this partnership—and the newly developed technology behind Tetra Pak’s aseptic packaging—Mori-Nu’s tofu is shelf-stable, with no need for refrigeration until the package is opened.

This particular convenience may be lost on many consumers, as retailers routinely place Mori-Nu tofu in the refrigerated aisle (and after purchasing it, customers assume the need to store it in their refrigerators at home). But it’s a major distinction of Mori-Nu tofu, which is among the biggest brands for silken tofu in the United States, sold everywhere from health stores and co-ops to Walmarts, Wegmans, and Krogers nationwide.

Thanks to recipes and serving suggestions illustrated on the packaging, the company has helped expand the repertoire of tofu uses in America, from vegan scrambles and classic Asian dishes to an invisible player in cake batter, pumpkin soup, and even meat loaf. Says Sherfey, “When I make mashed potatoes, instead of putting cream in to make it creamy, I’ll use tofu and blend it in, and it becomes extremely fluffy.”

This July, however, Mori-Nu is launching a new product that will present a different suggestion: “Asian Dessert Tofu,” which is lightly sweetened and flavored to resemble almond jelly. The image on the packaging shows soft mounds of tofu in a patterned porcelain bowl with a scattering of goji berries on top. The texture of this tofu is about the same custardy-soft set as another recent SKU, appropriately called “Super Soft” tofu, which launched last year. The image on that package depicts a wooden spoon holding a wobbly-looking mouthful of the product, while on the website, a bowl of tofu pudding—known as douhua, dou fu fa, or dau fu fa—with sweet toppings and syrup is shown.

Asian desserts such as these have been gaining more of a foothold in the United States in recent years. Asian dessert culture in general has been blowing up in US college towns, even prompting the “bobafication” of American chains like Starbucks. The new offerings from Mori-Nu were developed in response to these growing trends, and thanks to the expansion of Asian chains such as the Taiwanese dessert shop Meet Fresh, as well as mom-and-pop shops from coast to coast, tofu pudding is more visible than ever. That goes for sweet and savory-topped bowls alike.

Paul Eng sells many of both at his shop, Fong On, in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Originally founded in 1933, three generations of Eng’s family ran the shop, making fresh soy milk and tofu, until it shut down in 2017; two years later, he reopened the business in a new location, preserving many of his family’s traditional offerings, like dou fu fa, for a new generation of customers. For sweet dou fu fa, customers can choose from toppings like taro balls, red beans, and boba, along with ginger, brown sugar, or almond syrup; or they can choose a savory dou fu fa topped with the likes of scallions, fried shallots, and pickled radish.

In addition to retail customers, Eng has been providing fresh soy milk and tofu to restaurants, including Meju and—much to his surprise—non-Asian fine-dining hotspots including Eleven Madison Park and Bridges.

“I absolutely didn’t plan for that,” admits Eng, who notes that these restaurants are often using Fong On’s soy milk to make their own fresh tofu and tofu-like creations in-house, such as an uni-topped soy milk custard at Bridges. There have been many more restaurants that have inquired, but for now, Fong On doesn’t have the staffing or manpower to accommodate them.

“I think tofu in general—along with Asian cuisine—has finally come of age,” he says. “My parents and my brothers were doing tofu for such a long time, and there was always this thought of a broader audience, but then it was just thought of as a health food. Now it’s not considered a health food that’s strange or odd but part of the mainstream.”

It’s enough to have made Eng reconsider the scale of his operations—and the reach of his product. A few years ago, Whole Foods approached Fong On about carrying its soy milk and tofu products in stores, which Eng didn’t initially think was possible given the machinery needed for packaging. But after having learned some new techniques, he “sees a pathway” to that possibility.

Watching the way his dou fu fa delights even customers who’ve never tried the stuff before has been encouraging. Over the past five years since reopening Fong On, the crowd lining up for his soy milk treats at the shop every day has shifted from predominantly Asian to a diverse mixture of groups.

The other day, Eng recalls, a woman came into the shop after having seen someone walking down the street eating a cup of savory dou fu fa. She went up to Eng at the counter and said, “I want that! I don’t know what it is, but I want it!”