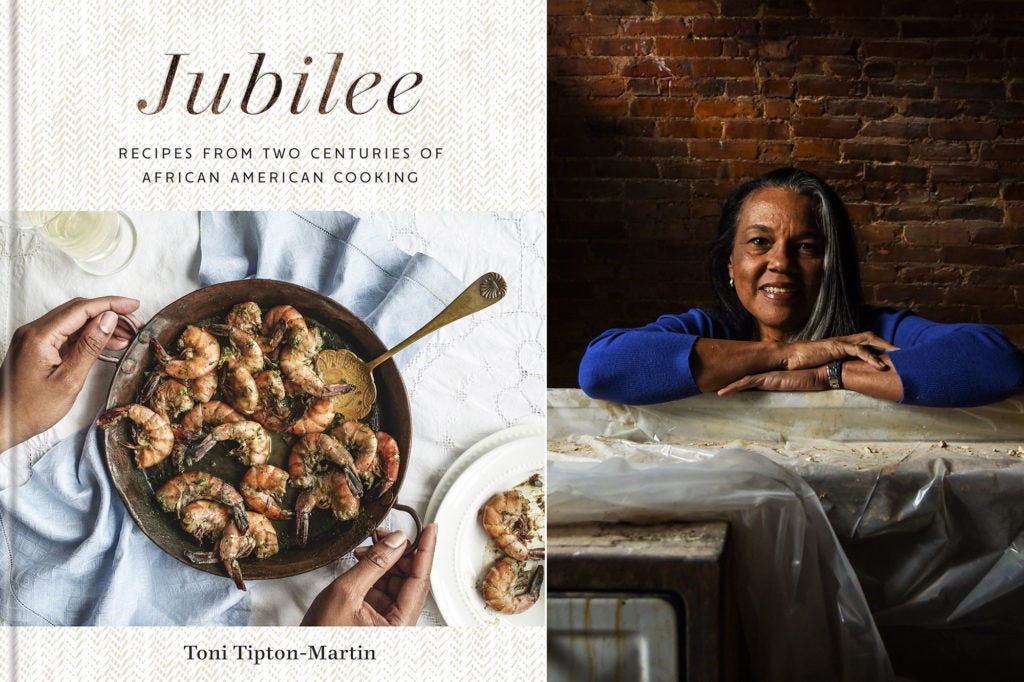

Toni Tipton-Martin introduced the forgotten founders of black cooking. Now she’s showing us what they cooked.

Toni Tipton-Martin has made it her life’s work to reframe Aunt Jemima, the iconic, reductive pancake figure that has represented black womanhood in American cooking since the late 1930s. Over the course of 30-plus years, the Los Angeles–born journalist and food editor compiled more than 150 black-authored cookbooks spanning over 200 years in pursuit of overturning the prevailing story line that white chefs and home cooks are the sole heroes of American gastronomy.

It’s strange to suggest that there was a time when black chefs were considered to be without agency or authority when considering What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking (1881)—originally thought to be the first book authored by a black cook—or A Domestic Cookbook by Malinda Russell (1866), later proven as the original text. Tipton-Martin’s mission to simply collect such texts functions as self-evident proof of black excellence in early American cooking, but when she published The Jemima Code in 2015, she redefined the history not only of black foodways but of American foodways at large. Now, with her follow-up, Jubilee, she’s translated the food of the Code with historical recipes adapted for a modern-day kitchen.

The first time I encountered Tipton-Martin was in late 2009, when she began posting to The Jemima Code, a blog where she first compiled the stories of black figures that had been left out of the dominant narrative of American food culture. As a young chef and the recent founder of the site Black Culinary History, I was hungry for these kinds of stories. The Jemima Code, with its Tiffany-blue background and defiant red kerchief—a direct challenge to the marginalized narrative of Aunt Jemima—stunned me. Here was a woman who had worked under Ruth Reichl at the Los Angeles Times and become the first African American woman to hold the post of food editor of a major daily paper, at the Cleveland Plain Dealer, a woman who seemed to wholly understand and embrace the power of acknowledging black culinary receipts. With her bold proposal, Tipton-Martin shifted the center of the food universe to a cast of largely unknown names that, until the late 1970s, had quietly represented the base of working culinary professionals.

Jubilee was always meant to be a companion piece, celebrating and bringing to life the food of the people featured in The Jemima Code. From French-Caribbean quick breads, fritters, and rolls to African-influenced gumbo and groundnut stew, these recipes stand as a record of the bloodlines borne out within black culinary tradition. With The Jemima Code, we learned about not only Leah Chase and Edna Lewis, but Liza Ashley, the Arkansas Governor’s Mansion chef who charmed the state’s first families with her chess pie, as well as Vera Beck, the Plain Dealer test kitchen chef whom Julia Child and James Beard sought out for her biscuits recipe. Now, Jubilee exhumes their work from the archives and ushers it to the fore. With it, Tipton-Martin has given us the gift of a clear view of the generosity of the black hands that have flavored and shaped American cuisine for over two centuries.

Back in August, I sat down with Tipton-Martin to talk about her process, the times that Jubilee will live in, and the necessity of reframing marginalized narratives.

[This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.]

Your career seems to have always been leading you to this space of culinary history, which is historically a white women’s field. It’s also coincided in many ways with the beginning of this modern era of food media. I’m wondering about how the initial mission of the collection and your approach to the scholarship changed with the zeitgeist?

I’ve always approached this project as a journalist on the hunt for a story. As far back as my days with the Los Angeles Times, I was reporting stories that addressed our community’s relationship with food from a health and nutrition point of view, but I was always curious about the people and the stories I couldn’t tell through that lens. I remember when Ruth [Reichl] came to the Times and asked me about my frustration with this framework. It was like being set free to write in a completely new way. She charged me to dig deeper and tell the stories I was interested in without a blueprint. I left the newsroom that day, and it took me three days to come back with my first story. I waited on pins and needles for her reaction.

The resulting story was the beginning of a paradigm shift for me personally and for the industry at large. I think today, with media forms changing so rapidly, the stories are far more personal, allowing writers to infuse themselves into the narrative. The thing that will never change is that the most powerful stories center people. When I began to collect the cookbooks, it was really about these forgotten gems. I’d be gifted an obscure book or come across an out-of-print title in an antique store, and slowly, a story was being born that told a counternarrative about the foundation of American cuisine.

I think of your work as wildly subversive, especially given the environment in which you began. To be one of the only black women navigating a mainly white food world—I’m wondering if you could talk a little about the vision it took to start building this canon of research before the zeitgeist was ready for it.

I had to convince a lot of people that there was power in these stories. I also had to convince them that I could present them without recipes. Very few people saw the vision, because our history is so hidden. It’s easy to dismiss or diminish these lives in the absence of written history, but we have to remember who had the power to record history. The journalist in me started with the source material. The books spoke to me and told me stories that were in direct contradiction to the tired tropes of deprivation and servitude. They showed such diverse lives and so much honor and joy that I knew I was onto something.

There were many discussions and versions of what the final book would become, but I’d always wanted to present these ancestors and the truth of their contributions to American cuisine in a way that would honor them. I’d hoped that it would resonate, and I knew the power of what I had, but no, I don’t think that at the time I really understood the way it would shift the conversation. It’s taken the subsequent years to form Jubilee into the project that it’s become, but The Jemima Code had to be first, to introduce the ancestors in archival form.

Once the reader consumes The Jemima Code and understands the 200-year timeline of black culinary history you’ve laid out, Jubilee becomes a tangible way for the reader to then cook the recipes. How did you approach the recipe writing with so much inspiration to draw from?

I’m not a chef, and although I write about food and cowrote A Taste of Heritage with Joe Randall, I wanted to develop the recipes from the point of view of the home cook who would hopefully want to integrate these deep culinary traditions into their everyday cooking. Our heritage is gracious and beautiful. I wanted to show how unique our culture is and to do so through the words and recipes of the ancestors. I want the reader to experience the food and traditions I grew up with that were full of pride and care—the attention to detail that a well-laid table expresses, and the flavor difference that preciously sourced produce brings to the dining experience.

I also had to make sure that, while the recipes read and tasted modern, it was clear that the inspirations were coming through the lens of the women and men of the code. The book is part African diaspora, part regional American, and all heritage, without compromising the source material.

Back in 2015, you hosted Soul Summit to commemorate the 150th anniversary of emancipation. At that event, noted journalist and food writer Lolis Eric Elie shared his manifesto on the notion of soul food as a starting point to define black foodways. In reading Jubilee’s recipes, it feels like you’ve unlocked a blueprint for these modern black foodways. What is your sense of the possibilities for black chefs in translating this wealth of culture into a modern culinary identity?

There is no one black identity. There is a shared culinary heritage that black hands have gifted this country, and I think the way that’s expressed today should be through personal narrative. I wrote the book and organized the chapters in the way I dine and entertain. I wanted to show how these traditions are expressed from my personal point of view growing up in California, having worked and lived across the country. I also wanted the recipes to reflect how cultural influence and regional specificity influence how we consume culture. There is cultural infusion that allows for unique or unexpected ingredient choices added to traditional dishes that is also part of the black migration story that I felt compelled to include.

You talk a lot about the choices you’ve made stylistically in both The Jemima Code and Jubilee. There is a presence and a beauty to both books that seems to be part of your own personal presentation and how you move through the world. Can you talk about the power of beauty?

So much of my work is about restoring dignity to our ancestors. So much of the narrative is about deficit and struggle, and I wanted my books to be beautiful as an homage to the power and beauty the books in the collection all showed me. These lives, these people of the code, deserve it. The Jemima Code was about showcasing the books themselves, so paper quality and the cover art were the focus. It’s a coffee-table book that is also a reference book, but it lives as an art piece. Jubilee, as a cookbook, had to be tactile. I wanted to be sure that I could bring to life these recipes in a way that translated as a usable manual but was still evocative and maintained the complexity.

The process was grueling, but in the end, the ancestors sent me Jerrelle Guy, who wrote the [James Beard] Award–nominated book Black Girl Baking. I knew I needed a team who understood recipes, could handle the food styling and photography, but would also have a love and respect for these foodways. I didn’t know I would find it all in one person, but once I spoke with Jerrelle and explained my vision, she was able to take the ball and run in a way that makes me so proud. Beauty is not a vice. It conveys the message that love and respect are being paid.

You live in Baltimore now. Can you talk about that move and what you have in store for this next phase of your career and the collection?

I’m restoring one of the “Painted Ladies” row houses in Charles Village, and the building is speaking to me. I feel the need to create a space for fellowship. I envision a hub for all of you to come and create and cook that really fosters the energy of the collection. I’m thinking about a home for The Jemima Code book collection and, for the immediate future, just waiting for the world to receive Jubilee.