For many women in India’s urban areas, kitty parties function as both an informal savings bank and a much-needed social outlet.

It has been two years since Seema Chadda’s husband passed away, but only three months since she started leaving the house again. Seema, who is 65 and lives in South Delhi, is an old friend of my father’s. For years I have heard legends—some with well-placed hyperbole—of her cooking, and the way she would soar around a room with trays of steaming parathas for scores of hungry men. After she lost her husband, Seema gave up many of her usual social outings. But she slowly got back “in the scene,” as she says. And for Seema and many other Indian women, that means the kitty party scene.

In India, a kitty is a group of women that serves two purposes: It functions as a daytime party held once or twice a month, and as a way for the group to build up a small stockpile of money to keep on hand in case any one of its members is hit with a financial crisis. When kitty members gather, each contributes a predetermined sum of money that is given to the host, who then arranges food and activities for the members. As much fun as they can be, the gatherings also provide a valuable social and economic outlet.

“When I was a young woman, I wasn’t allowed to work,” Seema recalls. “Kitty parties meant we could have outings to meet with friends and do whatever we wanted once a month.” She has known the members of her kitty, whom she refers to as “sisters,” for almost 40 years now. “When I found myself all alone,” she says, “it was easier for me to go back into the world through them.”

The exact origin of the kitty is unclear: One theory holds that it developed from the Hundi (Hindi for “savings box”) system in which one person would order a second, in writing, to pay a sum of money to a third. Another posits that kitties descended from the kuri or chitty system, an indigenous rotating savings establishment used by women in rural India to pool money and direct it to a random recipient.

But while indigenous savings systems have been common in India since the 16th century, kitties are a much more recent phenomenon: The first were documented in the 1950s. And they are also distinctly urban and class-based: Most of them function as gatherings of middle-class—and mostly married—women in metropolitan areas of North India and Pakistan.

Kitty membership is granted in many ways; women are frequently relatives, but just as often, their alliances are reflective of class. Wealthy women tend to meet through husbands who work together, while middle-class women meet in their neighborhoods or through their children’s schools, and working-class women come together through their professions. Members almost always belong to the same economic class, and new members are introduced into the group by the older members.

While kitty parties are crucial as informal savings mechanisms, food is central to them. A menu usually consists of snacks like dahi bhallas, or cornflour balls dunked in yogurt and a sweet sauce made from fennel seeds, garlic, and cumin; fried cheese cutlets; and bread pakodas, a favorite North Indian snack of greasy, deep-fried bread slices clamped around a sliver of paneer. Occasionally, kitties also offer lunch, which is always vegetarian to ensure everyone can eat everything. “I would make a pulao, daal makhani, sarson ka saag [a Punjabi dish made from cooking mustard spinach leaves],” says Seema, adding that she learned all the recipes from her mother in-law.

During the first two decades of Seema’s kitty, the women usually cooked, but as they got older, restaurants flooded New Delhi, and prepping for meals became a laborious task. These days, the women prefer to dine out, with each host choosing the restaurant for the gathering. Some restaurants have set menus that cater to these women; kitties also tend to flock to restaurant chains, like Bikaner Vaala and Haldirams, that serve chaat, or spicy, fried street food.

“Last week we went to a restaurant called Laid Back Cafe, where I ate an Italian risotto for the first time,” says Seema. “It’s rice! A little bland. But I liked it.”

Seema’s kitty is one of many styles. In the more extravagant ones, Seema tells me, groups of women have been known to fly to destinations like Florence for two-day luncheons. Others have themes: women dress up like schoolgirls in pigtails or Bollywood stars from the ’70s. But for all kitties, the main goal remains the same: to gather in a space with your women friends. “No men allowed,” Seema stresses; kitties are always “all girls.”

This was true of all the kitties I attended: Men were nowhere to be found, unless they were delivering a dish from the kitchen or bringing snacks while the ladies talked. “Men think all we do at kitties is gossip,” says Abha Kumar, a woman in her late 50s whose lunch kitty I joined at the Panchsheel Club, one of Delhi’s oldest. “But I read somewhere that gossip is a bad word for a good thing. What is wrong about unloading your troubles onto your friends?”

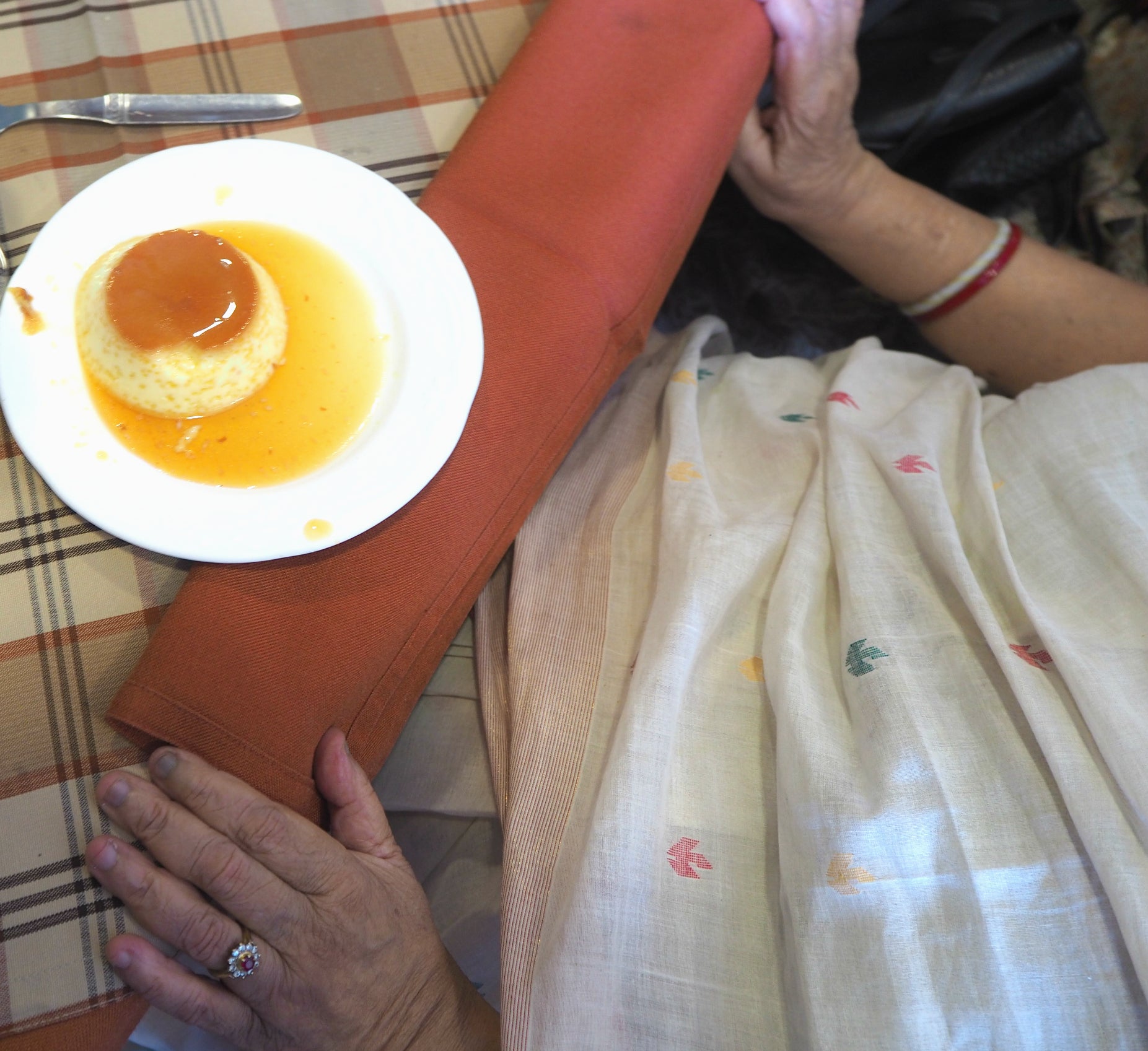

Abha’s kitty began meeting in 1982. All of its members are distantly related to one another, and unlike those in Seema’s kitty, they don’t hit up the city’s new restaurants but instead stick to what they know best: snacks and meals at the city’s best clubs. Clubs in Delhi are styled after British clubs in which members eat and drink and play sports together, and the menu that Abha and I are eating consists of colonial favorites: cutlets and potato chips, an “English bake” in which vegetables are layered with cream and cooked in the oven. The ladies hurry through their meal in anticipation of a communal favorite: caramel custard, a steamed bittersweet rice pudding beloved by Indians all over the subcontinent.

“[The kitty is] a way to not become completely neurotic,” says Abha as she watches her friends inhale their custards. “To stay connected.”

Later that evening, I attend another kitty, this one in a neighborhood not far from where Abha and her friends had lunch. “When I moved here, I didn’t know anyone. Then my mother-in-law began taking me for her kitties,” a member named Julia Grover tells me. Originally from Shillong, Meghalaya, one of India’s easternmost states, she moved to the capital after she married her North Indian husband. When she arrived, she found a city with a language, temperament, and palate alien to what she had previously known.

“Initially, I couldn’t cook or eat like people in the North,” she says. “But I knew they wouldn’t be able to digest [my own] northeastern flavors, either. We eat a lot of steamed vegetables, raw roots—you know, not everything put inside masala and dipped inside chutneys, like in Delhi. So I made momos [dumplings], which is quite common in Shillong as snack food, and Delhi people love momos, so it worked.”

The neighborhood kitty that Julia belongs to is the most informal kind of kitty; its members typically gather in a central park for food and tambola, a bingo-like game that originated in southern Italy and is played at kitty parties everywhere. Joining a kitty “really gave me something to do, a way to make friends,” Julia says. “Today I can speak the language, and I have all these women I can rely on.”

Despite the sense of community and connectivity they foster among women, kitties haven’t been immune to criticism, much of it from women. They have often been looked down upon as antiquated, anti-feminist affairs, unfit for the constantly evolving Indian woman and unwelcome in progressive circles. And with more and more women entering the workforce, kitties have declined in popularity since the 1970s and ’80s. This shift is particularly evident in Julia’s kitty, which is largely comprised of women in their 80s; at 52, Julia is its youngest member.

“I only joined two years ago; before that I looked down on them,” says Jayashree Chowdhury, an attendee of Julia’s kitty. “There is some sense of an idea that kitty parties are not for progressive women, not for intellectual women. But I have found solace in them. Despite myself, I will admit!”

Despite their decline, kitties remain ubiquitous among married women who aren’t allowed to work, as well as women who move to new cities, the wives of young businessmen in smaller cities, and women from wealthy families who aren’t otherwise allowed to make social contact outside of the family context. They allow these women to feed their appetites and whims, eat and talk as much as they like, and enjoy themselves, unobserved and uninhibited in a society that, even today, is ruled by laws decreed by men.

As Julia distributes snack boxes of kachoris, spicy pastries stuffed with lentils and potatoes, the older women begin a relentless game of tambola. As the ladies play the numbers and squares, they also, for an hour, trick fate and carve out their own destinies.

“Through food we exchange recipes, and through recipes, we exchange ideas,” says Julia as she sits down to watch the women play. “That is what kitties are about. Sticking together. Being independent. And evolving.”