Each Southeast Asian take on peanut sauce tells a different story.

Peanut sauce is a familiar sight in Southeast Asia—trickling down chicken skewers on a street-side charcoal grill in Bangkok or mixed into bowls of thin rice noodles at a hawker stand in Singapore. There’s a rush of creaminess, heat, and tang that instantly hooks you.

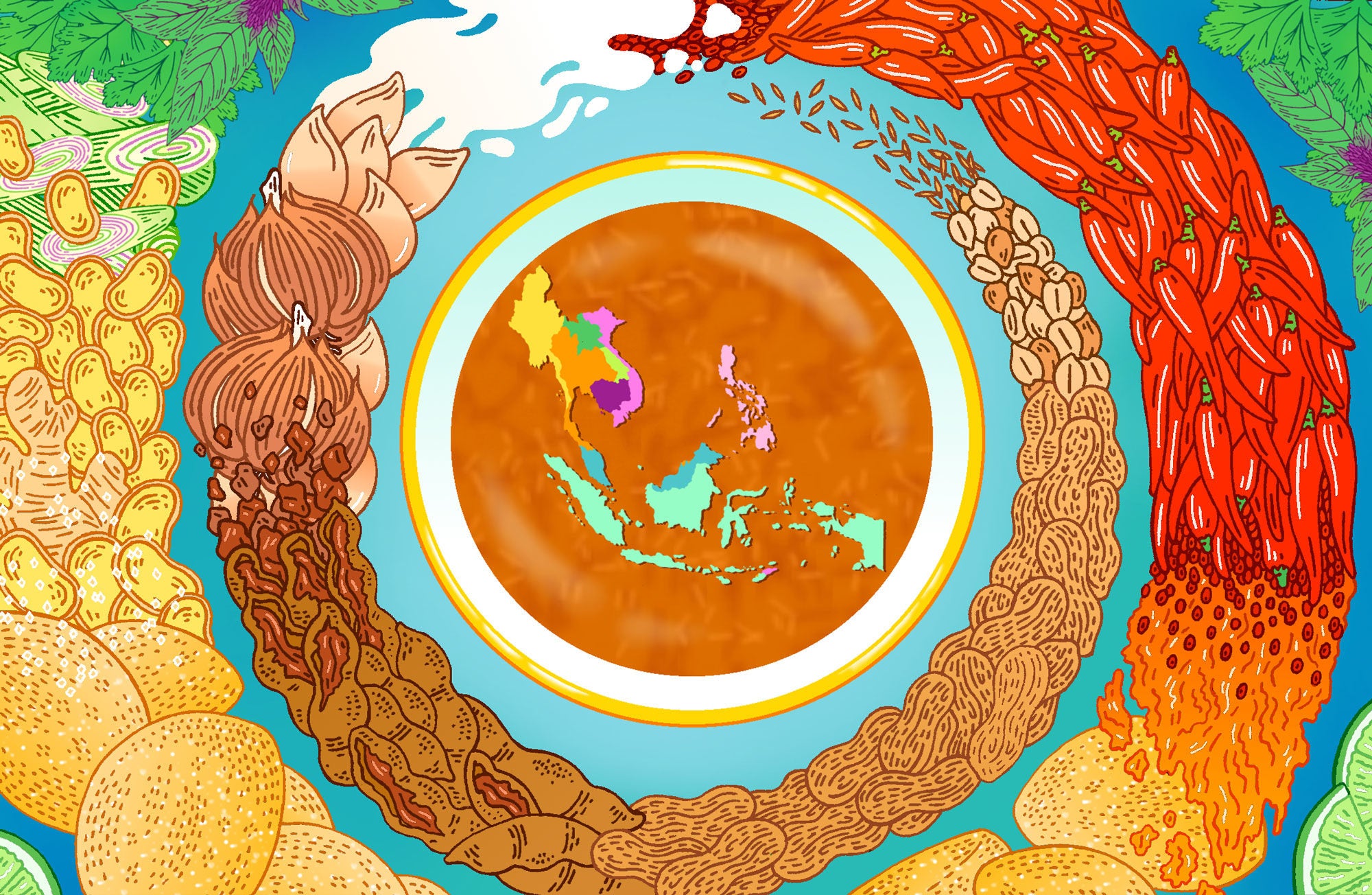

The reason for that is because peanut sauce combines some of the region’s most defining ingredients, most commonly: sweet palm sugar and coconut milk, briny soy sauce, aromatic herbs like cilantro and Thai basil, and fiery spices—cumin, crushed red pepper, black pepper. Blended together with a cup of fried, roasted, or unroasted peanuts, they form a dressing in which opposite ends of the flavor spectrum collide.

“Each peanut sauce tells a different story,” says Corinne Trang, a food writer and author of multiple Asian cookbooks. In the United States, “peanut sauce” tends to be shorthand for the sweet, peanut-butter-y sauce that you’re as likely to find alongside Cheesecake Factory chicken satay as you are on a bowl of noodles from a mall food court. Americanized peanut sauce has its own narrative of ingredients—often featuring peanut butter as a shortcut and sweetened with maple syrup or honey. But across Southeast Asia, each drizzle of liquid gold has its own personality, with many faces informed by local influences.

“Its profile is at once complex and balanced—you’ve got the sweetness and the spiciness, the richness and the sourness,” says Trang of Southeast Asia’s flavor matrix. Skewers of satay—the most ubiquitous vehicle for the sauce—are just the start in its birthplace of Indonesia.

Known as bumbu kacang, peanut sauce is to Indonesia as olive oil is to Italy—and it’s been a kitchen staple ever since its introduction in the 16th century by the Portuguese. The all-purpose sauce gives a lift to blanched vegetable plates of gado-gado and adds heft to ketoprak, a warm combination of tofu, bean sprouts, rice vermicelli, and rice cake. It’s also the go-to topping for fish-filled dumplings like siomay, and it accompanies ayam taliwang (spicy roasted chicken) as part of a tomato and chile dip.

Bumbu kacang begins with frying or roasting raw peanuts in vegetable oil before grinding them together with the ABCs of local cooking using a mortar and pestle. Spoonfuls of pasty palm sugar (which, unlike white sugar, is unrefined and comes in a jar) and kecap manis, a soy sauce blended with more palm sugar, bring sweetness; while tamarind, garlic, and ginger, plus a smattering of salt, chiles, cumin, lemongrass, and a hint of lime juice bring out both subtle and pungent aromatics.

“Sometimes coconut milk is added. Other times, chicken stock replaces water to thin it out. In Java, it’s sweeter, as they use more sweet soy sauce and palm sugar; in Bali, it’s spicier, with lots of chiles,” says Antoine Audran, culinary director of Potato Head Group, which has Indonesian restaurants throughout the region.

Beyond Indonesia, peanut sauce has localized itself into neighboring cuisines. “Singapore and Malaysia have the closest versions to Indonesia’s peanut sauce, given their [geographic] proximity to it,” Trang says. In Singapore, it takes the form of a predominantly chile-based dressing poured over rice vermicelli to make satay bee hoon, a hawker specialty, whereas skewers of satay in Malaysia call for shallots, galangal, ginger, and lemongrass (but not lime juice) to accompany squares of compressed rice cakes called nasi impit.

Thai versions favor heat and deeper umami, mixing in red curry paste and shrimp paste. “Peanut sauce isn’t central to Thai cuisine,” says Chicago-based Thai cookbook author Leela Punyaratabandhu. “But it’s still part of street food culture—you’ll generally find it at hawker stalls, where it accompanies satay.” Tuong dau phong, Vietnam’s take, includes fish sauce for extra pungency and is thickened with hoisin sauce. Aside from grilled meat, freshly wrapped spring rolls serve as a mildly flavored vehicle for dipping into the layered, nutty sauce.

Sometimes it’s a mash-up of all of those things, not necessarily confined to one country’s way of doing it. Punyaratabandhu’s peanut sauce recipe mixes traditional flavors with her Chicago pantry. “It uses granulated sugar and vinegar instead of palm sugar and tamarind pulp, and I’ve streamlined it by replacing ground peanuts with all-natural peanut butter,” she notes. Trang learned her version, featuring a touch of coconut milk for creaminess and chicken stock for extra flavor, from her Ho Chi Minh City relatives, who settled in Vietnam by way of China and Cambodia. In each peanut sauce recipe, every ingredient is a hint about its own backstory.