How Momofuku’s slow-roasted pork became David Chang’s signature “fajita moment.”

Back in 2009, Steph Le was working at a passport office in Vancouver, British Columbia, and she was unsure of what the future held for her. Was this job all there was? She was craving a creative outlet, but what that might be, she didn’t know.

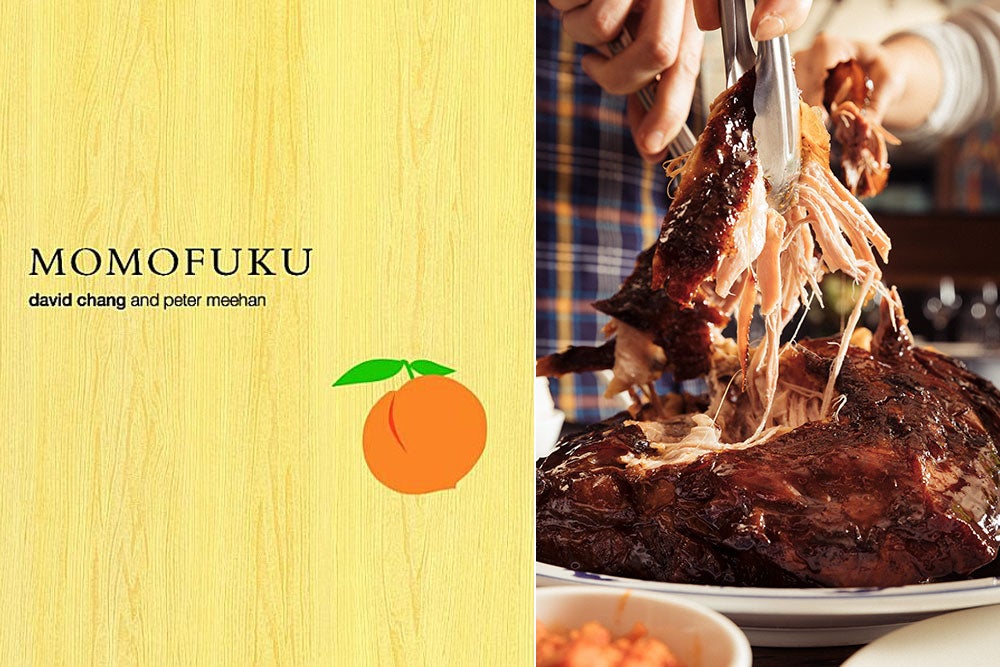

When Christmas rolled around, her husband, Mike Le, gave her a gift: Momofuku, a cookbook by David Chang, the revolutionary (then, now, and likely in the future) chef behind the then-five-year-old Momofuku Restaurant Group, and his coauthor, Peter Meehan, who would go on to found Lucky Peach magazine with Chang’s backing. In three sprawling, hyper-detailed, and casually frank sections, each representing one of the Momofuku restaurants (Noodle Bar, Ssäm Bar, and Ko), the book told Chang’s story—the Korean American who adored fine dining and Japanese cuisine but also craved instant noodles and fried chicken—and it reveled in pork, noodles, kimchi, Benton’s bacon, old-school techniques, “ghetto sous vide,” country ham, red-eye mayo, and oysters on everything.

The book had just been published by Clarkson Potter a couple of months earlier—October 27, 2009, nearly 10 years ago to the date—and it was greeted with rapture. Publishers Weekly gave it a starred review. In The Atlantic, Tejal Rao wrote, “I read it in one sitting and was immediately taken over by a very strong need for hot broth and noodles. It made me irrational.” And in Saveur, Sara Dickerman was already beginning to track Chang’s influence: “What Chang sensed when he opened Noodle Bar was that people wanted to eat very well but that they also craved spontaneity and informality. Nowadays, whenever I see a trained chef open, say, a late-night taco stand, I know he’s been drinking in some of Chang’s enthusiasms.”

This lust for high-end artisanship and low-end conviviality was about to completely envelop 28-year-old Le, who, at her husband’s suggestion, decided to cook her way through the whole book—and blog about it.

On New Year’s Day of 2010, Le launched Momofukufor2.com. Over the next 231 days, she would go on to cook all 98 recipes, from Noodle Bar’s ramen—a potentially multiday effort that encompasses six separate recipes—to the kimchi consommé. Sourcing some ingredients (like shiso leaves and pig heads) was a challenge, but she persevered, finishing in mid-August with Ko’s ingenious shaved foie gras dessert: “the dish I think we’ll never be able to take off the menu,” Chang and Meehan write, and correctly—it’s still there.

In the heyday of food blogs, Le’s focus on the Momofuku cookbook was, however, unique only in its single-mindedness. Over the next several years, the recipes were written about (and reproduced) in dozens of blogs and mainstream publications, from Frugal Hausfrau to Bon Appétit. And of all the Momofuku hits—the ramen, the pork buns, the Brussels sprouts tossed with bacon and fish-sauce vinaigrette—no recipe received as much attention as the Bo Ssäm.

It is a remarkable dish—overwhelming but simple, connected to Chang’s roots but adroitly cheffed up, a restaurant showstopper within the skill set of any home cook. At Ssäm Bar, it was The Dish.

To make it, you dry-brine an 8-to-10-pound Boston pork butt in salt and sugar overnight, then roast it gently for six hours, until the skin and fat and meat are pretty much tumbling off the bone. Then you cake it with brown sugar, crank the heat to 500 degrees to forge a pork-candy shell, and serve it alongside rice, kimchi, freshly shucked oysters, two sauces—ginger-scallion and ssamjang—and a few heads of lettuce, into whose leaves you wrap everything else. (That wrap is a ssäm.) Each bite is a bit of hocus-pocus that blends nearly every conceivable texture and flavor, from the sharp, spicy crunch of the napa cabbage kimchi to the fatty, sweet richness of the pork to the briny, binding mush of the oysters.

The dish, Chang explained in a statement to TASTE, was his attempt, at Ssäm Bar, to create “a ‘fajita moment’—you know, when that sizzling platter comes out of the kitchen, everyone cranes their necks as it glides past them, and then they all have to have one.” At first, he’d give it away free when the restaurant was busy and tell curious onlookers that it had to be ordered in advance and was only available during off-peak hours. Today, preordered, large-format dishes, like the “cracked at the table” Beggar’s Duck from Mission Chinese or the NoMad’s lacquered roast chicken for two, are commonplace, but back then the Bo Ssäm was a novelty in New York restaurants, particularly at a raucous place like Momofuku. But it turned out to be crazy popular—and, at $180, a big earner. (Today, it’s $250.)

“That’s how we stayed in business,” Chang said.

“The funny thing about the recipe itself,” he added, “is that it’s almost nothing like a traditional bo ssäm. If you go to a Korean restaurant and order bo ssäm, you’re going to get a platter of boiled or steamed pork belly. I like the fact that the cookbook kind of gaslit people that way. Just because I’m a Korean guy doesn’t mean that everything I’m telling you is actually Korean.”

Just as funny is how easy the recipe is, as Sam Sifton noted in a 2012 New York Times Magazine column, aptly titled “The Bo Ssam Miracle.” Recipes like this, he wrote, “make any cook appear to be better than he or she really is, elevating average kitchen skills into something that approaches alchemy.”

Times readers certainly seem to agree. The accompanying recipe has five stars, based on a whopping 2,249 ratings, with hundreds of reader notes detailing tweaks to the brine, how to prepare smaller pieces of pork, and alternative sauces. That may not put it in league with the Times’s 50 most popular recipes (the five-star mac and cheese has 8,000-plus ratings), but it’s quite an achievement for a book from, as Rica Allannic, its editor, put it, “a New York City–based restaurant that sounds like ‘motherfucker.’”

Which is to say that, despite Chang’s circa-2007 reputation as a nascent star, Momofuku was not an obvious slam dunk for everyone involved in its publication. “There might have been a little bit of a question about national appeal,” Allannic said. “I mean, we were never going for a Walmart audience, but you want to make sure [it’s not going to repel mainstream readers]. And some places did, in the beginning, have concerns about all the F-bombs inside the book, but they later came around. Not Walmart, but other places.”

Even Allannic had to come to terms with Chang and Meehan’s occasionally raw tone. “They were talking about some darker stuff, like depression and tough days. And I was like, ‘Okay, but then it got better?’ And they were like, ‘No, not really.’ And I kept trying to turn it around to come full circle, and then everyone has a happy ending, because this is America.” Eventually, she said, “I let go of that and realized it didn’t need to have an ending wrapped up in a bow. It was what it was, and it was truthful to that period of time.”

That time has passed in many ways. Chang and Meehan haven’t spoken since March 2017, when their business partnership, which had funded Lucky Peach, came to a reportedly acrimonious end and the beloved magazine shut down. For years now, they’ve lived separate lives.

But as Roland Barthes might have argued, Momofuku has a life separate from those of its creators, and it’s that existence we can now look back on with perspective, to understand how much has changed in the past decade.

“Back then,” said Steph Le, “Asian food wasn’t like what it is now. Right? Even living where we lived, where there were a lot of Asian groceries, there were still some things that—like light soy sauce, like [usukuchi] shoyu—they don’t have. Even now, that’s like a specialty ingredient.” Benton’s bacon was a rarity. Meat glue had to be special-ordered.

Today, she noted, you can get those things on Amazon, supermarket chains like Ralphs carry kimchi, and ramen and pork buns are facts of food life across North America. Le herself, meanwhile, is no longer at the passport office—she’s a professional blogger who runs the award-winning IAmaFoodBlog, and she has written her own cookbook, Easy Gourmet.

Momofuku made that career possible, along with the careers of folks like Ivan Ramen chef-owner Ivan Orkin, who gives Chang credit for transforming the American image of ramen. “Ramen was not considered a cuisine,” Orkin said. “Because ramen has no guidebook, it’s this combination of food being tasty, the master being interesting—the soundtrack.” Not only that, but Orkin appeared on the cover of the first issue of Lucky Peach, and the magazine’s coeditor, Chris Ying, is now Orkin’s cookbook coauthor.

In one small way, however, food culture has moved on from Momofuku. The book is clearly for carnivores, with its lavish recipes pitching a diet of maximal pork and beef and its inclusion of bacon in almost everything, and that can seem out of step in an era defined more by the veg-centric recipes of Yotam Ottolenghi, Jessica Koslow, and Alison Roman.

“Now, definitely, people are moving more toward [meat as] a special occasion—or not special occasion, but like a less-often kind of thing,” said Le. “I don’t want to say ‘dated’ either, but it was a moment in time.”

Still, when special occasions do come along, there’s always that Bo Ssäm—easy as hell to make, and a crowd-pleaser like no other. “They smell it and they look at it and they just go crazy,” Chang told Sifton in 2012. I cooked it for friends the other night, and I can assure you: In 2019, it’s still true. And it’ll be true in 2099, too.