Today, more than 800,000 food products are certified kosher by the Orthodox Union. It all started with a chemist, a rabbi, a pickle company, and a brand of soda.

In the early 20th century, grocery shopping quickly became easier for most Americans. Industrial food systems and miracle ingredients like glycerin and gelatin introduced hundreds of cheap, shelf-stable, and mass-produced foods to a growing (and hungry) population. But for the millions of Jews living across the country in the 1920s, this bountiful new age brought perils along with convenience.

It was suddenly impossible to tell, when shopping at shiny new supermarkets, which foods were kosher and which were not. Dairy worked its way into milk chocolate, hidden grains undermined Passover restrictions, and glycerin (derived from nonkosher animal parts) preserved, sweetened, and moistened everything from bread to ice cream to beef sausage casings. But first Heinz in 1927 and then Coca-Cola in 1935 heeded demands from the Jewish community to create kosher products, unintentionally setting a precedent that would open modern groceries to devout Jews across America.

Most companies, it turned out, were overlooking their Jewish customers not out of bigotry, but out of ignorance of kosher law, or kashrut. Millions of immigrants fleeing poverty and persecution in Eastern Europe quickly ballooned the Jewish population in America up from 230,000 in 1880 to 4.2 million by the time immigration quotas were established in 1924 and 1927. Before this influx, the largest American food manufacturers had little reason, or opportunity, to learn about the dietary restrictions keeping their products out of Jewish homes. This all changed when two Jewish community leaders decided to educate these companies about kashrut.

The first was Abraham Goldstein, a New York City–based chemist working at the Orthodox Union (OU), an early national organization of Orthodox synagogues that represented congregations across the country. The OU hoped to unify English-speaking Jews in the U.S., taking up causes such as kashrut on behalf of the Orthodox community. Goldstein spearheaded the union’s division of mashgichim, kosher inspectors who were respected community figures with enough authority to examine a company’s food production and assure the public the company followed all necessary Jewish laws. Their objective was to help the Jewish community determine which products were safe for consumption.

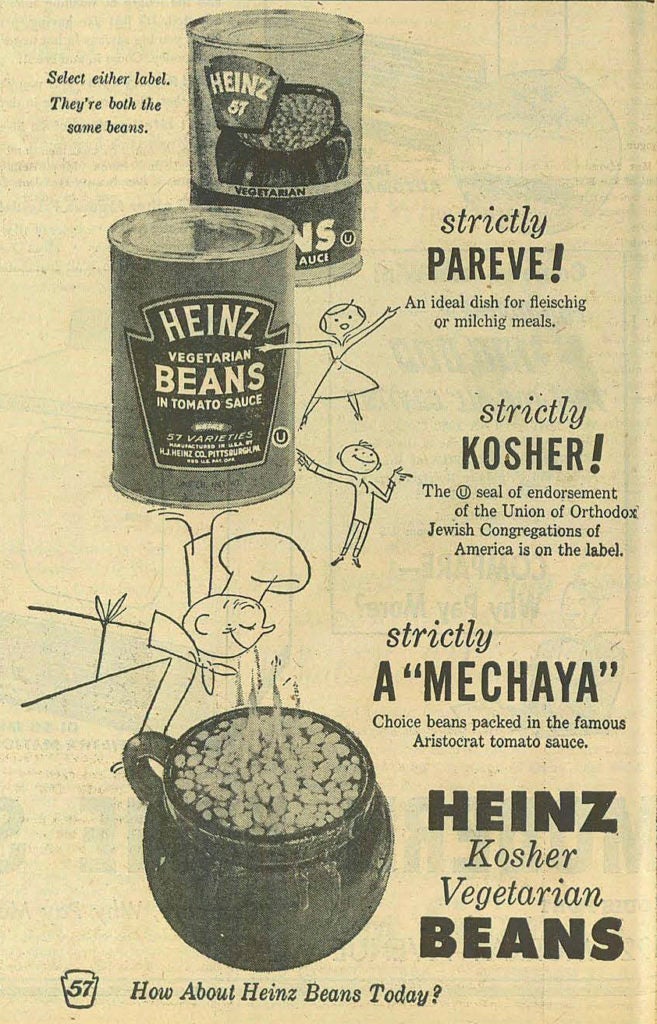

A Heinz ad from the American Jewish Outlook, December 9, 1955 (courtesy of the Pittsburgh Jewish Newspaper Project)

After a few successes with smaller manufacturers, in 1927 Goldstein approached the Sharpsburg, Pennsylvania–based Heinz. The company was the largest producer of pickles, vinegar, and ketchup in the country, with 6,000 employees and 25 factories. Founded by an American born to German immigrants, Heinz sympathized with appeals from European immigrants trying to navigate American culture. The company agreed to Goldstein’s inspections, and it turned out that the company’s practices were already aligned with Jewish dietary laws.

As a result came the first symbol to demarcate kosher status on a nationally marketed product. The OU had given its first kosher certification to Loose-Wiles Biscuit Co. in 1924 for Sunshine Kosher Crackers, but the crackers sported a complex seal featuring the OU’s insignia in Hebrew. Heinz requested a simpler logo, and together with the OU, the company developed the symbol that now adorns hundreds of thousands of kosher products, the letter U within a circle, a symbol that all consumers could understand regardless of Hebrew literacy.

In 1933, while Goldstein continued to spread awareness of kashrut, the American rabbinic community summoned Atlanta rabbi Tobias Geffen to seek out kosher certification for another staple of American grocery stores: Coca-Cola.

“Jews started using Coca-Cola for Passover, especially during Prohibition, when there were shortages of kosher wine,” says historian Roger Horowitz, author of Kosher USA. The company had advertised heavily in the Yiddish press for years, and the soda had become a common drink to serve to children at Seders. This growing popularity sparked question and debate about whether the drink could be considered kosher.

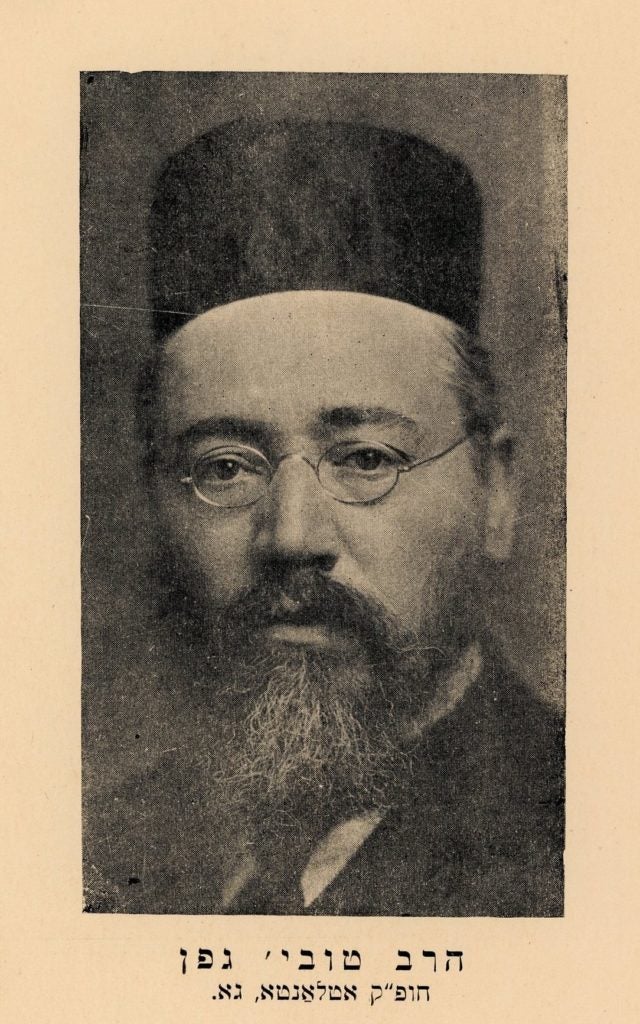

Rabbi Tobias Geffen (courtesy of the Geffen family)

“There is a tradition in Ashkenazi law that you ask the local rabbi on an issue of kosher law,” Horowitz tells me. Geffen had established a reputation as one of the few rabbinical scholars in the American South, making him perfect for the task of investigating Coca-Cola. Starting in 1927, Geffen began receiving increasing inquiries about Coke, eventually deciding to investigate the company personally.

Coke was notoriously protective of its secret formula, but Geffen had a friend inside the company, general counsel and Reform Jew Harold Hirsch. His grandson David Geffen tells me that the request was met with resistance at first: “My grandfather, who was no slouch, said to Hirsch, ‘Well, if I can’t see the secret formula, I will have to rule that Coca-Cola is not kosher and not kosher for Passover.’”

Six months after pressing Hirsch for access, Coke capitulated, and the rabbi became one of a handful of people to learn the Coke formula down to its most secret ingredient.

As he described in his 1935 teshuva, or kosher ruling, Tobias Geffen identified two strikes against Coke. The primary concern was Coke’s use of glycerin, a byproduct of soap manufacturing derived from parts of nonkosher-slaughtered cattle and pigs. Although deferring to secular science was unheard of for an Orthodox rabbi at the time, Geffen broke with established rabbinic authority and sought help from the chief chemist of the state of Georgia, who informed him that glycerin made up 0.09% of Coke by volume.

Geffen suggested Coke switch its glycerin source from animal parts to cottonseed oil, a change that required the company’s glycerin supplier, Procter & Gamble, to re-engineer its supply chain, too. Geffen also suggested swapping the grain-based alcohol used in the manufacturing process for one derived from beets or sugar cane. Coke (and Procter & Gamble) agreed to all of Geffen’s requirements.

According to David Geffen, the rabbi’s signature adorned bottles produced in Atlanta starting in 1935, but Coke eventually adopted the OU symbol established by Heinz and still sports the logo today. David Geffen adds that although it was far less publicized, his grandfather also quietly gave his approval to Pepsi when the company approached him in 1942, hoping to keep up with Coke.

Both Goldstein and Tobias Geffen faced opposition from other rabbis for their decisions, especially Goldstein for his reliance on secular science. The OU even ostracized Goldstein for challenging rabbinic authority as a common Jew using chemistry. Yet both men left outsized impacts on kashrut by embracing modern scientific methods. Geffen’s scientific analysis of glycerin’s role in the Coke formula set a precedent and a methodology for future mashgichim to duplicate.

A Heinz label in 1927 featuring the standardized OU symbol (courtesy of the Senator John Heinz History Center)

In 1935 Goldstein went even further, launching the Organized Kashrus Laboratory to aid rabbis with scientific analysis and test foods for kosher certification. In each issue of the lab’s quarterly journal, Kosher Food Guide, Goldstein answered dozens of letters from concerned Jews with kosher quandaries, eventually giving his certification to brands like Kellogg, Crisco, Kraft Miracle Whip and Hershey Chocolate Syrup.

The cases of Coke and Heinz hardly settled kosher debates overnight, and not all popular food companies decided to follow Coke and Heinz’s lead. Horowitz tells me Hydrox, an early competitor of Oreos, survived for decades on the Jewish market because Oreos contained lard derived from pork and Nabisco, the manufacturer of Oreos, refused to alter its recipe. Only in 1998, when Nabisco finally nixed the lard, did Oreo finally squash Hydrox across all markets (although Hydrox did return to the market in 2015 under new ownership).

Several competing national kosher certification programs sprouted up in the decades following, and their symbols still compete for Jewish attention and trust at the supermarket, but the OU symbol remains the most prominent today, stamped on nearly 70% of packaged goods sold in American groceries, according to the organization. Today the OU alone certifies over 800,000 products produced by 9,000 facilities in 100 countries.

Despite their complex legacies, Goldstein and Geffen gave devout Jews the opportunity to engage with quintessentially American brands at a time when anti-Semitism was on the rise in America. David Geffen says his grandfather, who had emigrated from Europe following the Kishinev pogrom in 1903, understood the significance and symbolism of Jews joining fellow Americans in drinking Coca-Cola. “He wanted them to be able to have a kosher drink,” says Geffen. “And because Coca-Cola was the most popular, he wanted to make sure it was Coca-Cola.”

Lead image of Rabbi Baruch Poupko inspecting food at the Heinz plant in his role as a mashgiach in 1951, courtesy of the Senator John Heinz History Center