How an unlikely pairing became a classic in the canon of weird and great American cooking.

A memory: We’re all sitting around the dining room table when my grandmother brings out a platter full of sliced ham topped with pineapple rings, each with an electric-red Maraschino cherry placed dead center. They looked like gems, the cherries, and they caught the light like them, too. I’m eight, maybe nine. We’d had this dish the previous year, and we’d have it again the next. The table was decked in holiday linens. But about the ham: I couldn’t wait for the ham. This was before I would learn that the cherries came from a jar, the pineapple from a can, and, in the earliest versions she’d make, the ham from the same—and it was long before I might care about these things. I just knew it appeared before me and it was perfect and fancy. And that it made my mouth water. And that, slicing through it the way I assumed ladies should hold their utensils, I never felt more like a queen.

In my grandmother’s dining room, baked ham with pineapples wasn’t treated as a novelty or hidden away, tucked behind the gelatin salads and hotdish. It wasn’t a relic of the past, either. It was tradition. I’ve always thought of ham and pineapple, though, as making good culinary sense, which isn’t always the case in the canon of Weird and Great American Cooking. Do shredded carrots and Jell-O really need to be together? Do they??

“I think pineapple complements ham perfectly,” Allan Benton, owner of Benton’s Country Hams—a modern-day ham god worshiped at the Eastern Tennessee altar by the likes of Tom Colicchio and David Chang—tells me when I ask him why the heck this works so well. “Typically, when you’re doing a country ham, you need something sweet to neutralize the ham’s saltiness, and pineapple does this really well.” And it’s not just me and Benton: Pineapple shows up in ham recipes—atop the ham, in glazes slicking the ham, in shield-your-eyes versions of fried rice—the world over. But who, great genius of our time, did it first?

The saga of how pineapple found its way to ham begins all the way back on November 4, 1493, when Columbus made his second voyage to the “New World,” landing on what is now the island of Guadalupe. Columbus was pissed to find, instead of gold or silver, pineapples. Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, author of the first comprehensive history of Spanish America (and whose description and photo of pineapple would be the first ever in print, years later), was kinder, calling the fruit the most beautiful “of any fruits I’ve seen.” Pineapples made Columbus’s return trip back to Spain to be presented to Isabella and Ferdinand, who, according to Pineapple: A Global History, declared it his favorite.

It would take pineapples just a couple hundred more years to become globally adored—that’s breakneck speed in an era when travel and shipment were anything but. Scarcely available outside of their native homes of South America and the Caribbean—and a favorite of those who could afford to have them shipped—pineapples became known as the fruit of kings. European horticulturists spent decades willing them to grow far from their comfort zones; the Dutch brought one to fruit in 1687, the French in 1733. The whole process, of course, was stupidly expensive and turned out tiny, often-gnarled specimens. Pineapple: A Global History reports some efforts costing as much as £80 to produce one fruit—that would be $3,000 today. That makes pineapples, at least then, not just an edible luxury for fancy rich people. They were the Bentley of fruit, more status symbol than anything else.

Canning would—thankfully, eventually—devalue the $3,000 pineapples of the world. Invented in 1809 but not gaining steam as an industry until later in the 19th century, the technology created the possibility for once-scarce tropical luxuries to become normal, everyday. Essentially, it dethroned the king of fruits. “Canned food was doing something similar to the railroad and the telegraph in terms of speeding up time and unmooring Americans from the previous limitations of time and place,” says Anna Zeide, a food historian and the author of Canned: The Rise and Fall of Consumer Confidence in the American Food Industry. “So things like pineapple, which are geographically bound to where they’re being produced, are now suddenly being exposed to audiences who would have never been able to eat or afford a tropical fruit.”

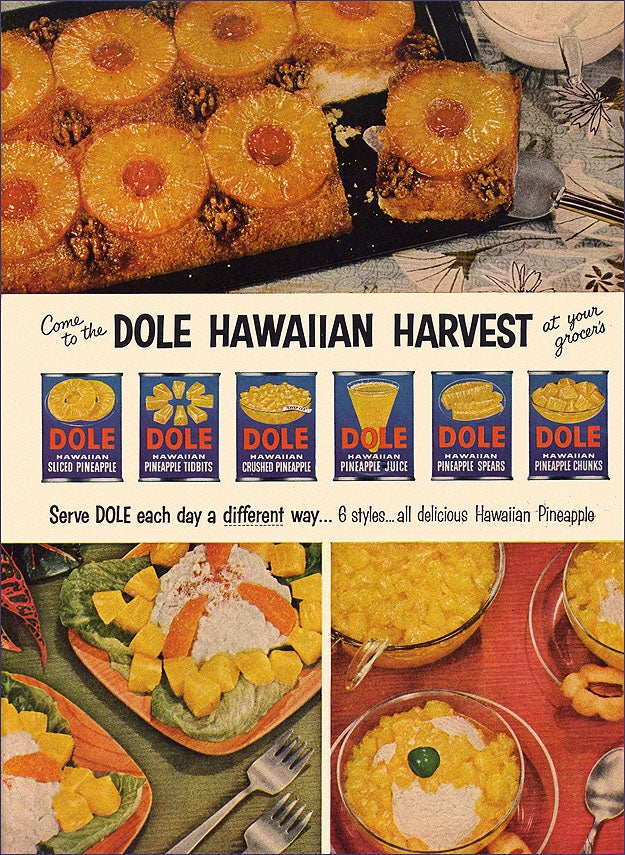

It’s this new technology that James Dole would lean on in 1900 after establishing the Hawaiian Pineapple Company—and competitors like Libby and Del Monte would follow suit. (Though not native to Hawaii either, the transplanted, close-to-the-ground pineapple plants thrived in the balmy climate.) By the early 20th century, pineapple was available to any cook, plebe, uncle, or child who wanted it. The only problem was that canning was slow to catch on with consumers: Companies had trouble convincing shoppers that what they said was inside the opaque tin really was inside, and there were outbreaks of botulism and food poisoning that some blamed on canned goods.

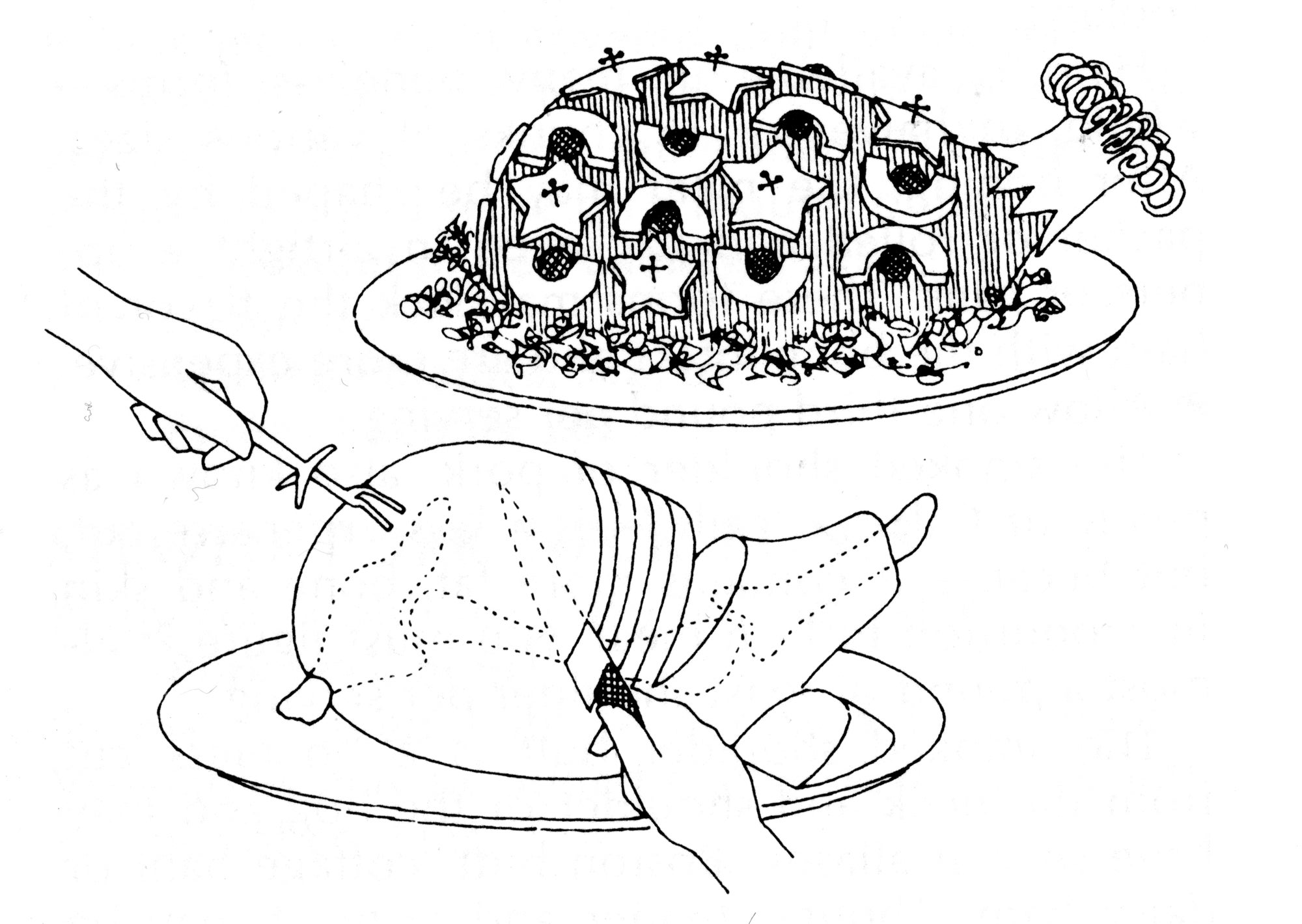

To help get their pineapple into more kitchens, companies took out ads in pages of women’s magazines. And they printed recipe booklets, like the Hawaiian Pineapple Packers Association’s 1914 edition, titled with all the enthusiasm of your should-have-retired-ten-years-ago third-grade teacher: “How We Serve Hawaiian Canned Pineapple.” Things got jazzier with the 1925 run, featuring a proto-Buzzfeed headline, “99 Tempting Pineapple Treats.” And in its pages: a recipe for baked ham with pineapple that predates similar recipes in early American cookbooks. According to Pineapple: A Global History, 1926’s “Hawaiian Pineapple as 100 Good Cooks Serve it” built on the ham and pineapple recipe from the year before. With pineapple showing up in plenty of meat and vegetable recipes, it revealed just how much pineapple was being used in savory American cooking.

It’s around the same time that the idea of Hawaiian tourism began to take root, and unapologetically inauthentic luaus—often featuring a roast pig with pineapple—became a standard part of the Hawaiian tourist experience. The same companies printing pineapple recipe booklets would later create luau versions. See: Del Monte’s“ Hawaiian Luau” booklet from the ’50s, with which you could “create a ray of Hawaiian sunshine for your table.” Or Dole’s, which promised you could “have fun and win fame” with a casual island feast. (You could also, as it happens, learn how to make fake leis out of “pastel toilet tissue,” a very good and practical skill.) Much like drinking a mai tai, baking a ham with pineapple rings was a way to bring a little paradise into your home. Can’t afford an exotic vacation? Throw a “casual island feast.” Cold winter night in New England? Not if you make this Hawaiian ray of sunshine. No matter that the flavor pairing actually worked, and well—baked ham with pineapple was a tropical destination stopgap.

I have no idea if my grandmother was dreaming of sandy beaches and palm trees when she first baked a ham and smothered it with tropical fruit. Neither does my family. They do recall her liking the dish because it was fast; she could “whomp it up in the blink of an eye!” as she’d say. She, the owner of the I Hate to Cook Book. Maybe she wanted to get on with it so she could spend more time dreaming about her tropical getaway—which punch she’d order, how many tiny umbrellas she’d request in it. Probably not. She was a staunchly practical woman. Then again, there’s nothing practical about Maraschino cherries, even if they do come from a jar. So maybe she was dreaming.