On accommodating physical disabilities and cottagecore fantasies while in search of fungi

I spy a flush of mushrooms perched high up on the birch tree. It takes me three tries to use my heavily stickered, foldable rosewood cane to knock them down, and after the bundle lands on the forest floor with a subdued thump, I run my fingers through the gills. My prize has the flowery edges and white flesh of an oyster mushroom. After brushing it to ensure it isn’t too wormy, I tuck it into my pack and move on, carefully prodding the freshly rained-on soil ahead with my cane before proceeding.

As a self-described mycophile, I’ve collected field guides for years, poring over glossy pages of magnified mushrooms while obsessively learning ways to identify them by their structure and spore print. I discovered the Northeast was a fungus gold mine and started foraging while living in Rhode Island three years ago, venturing out into the woods around Lincoln and Seekonk in Massachusetts. Foragers are notoriously hush-hush about the location of the prime spots, but I eventually coaxed a few foraging Facebook group friends into providing some map points, while finding a few of my own. After an introductory educational hike from a member of the Audubon Society, I began taking pictures and drawing the different species I came across, edible or otherwise.

Nature-centric hobbies are often inaccessible to me. I’ve identified as neurodivergent and a crip for most of my adult life, and I began using a cane in the past few years to assist with my fibromyalgia and chronic pain. Hiking, camping, and foraging are all activities that most believe require physical strength, stamina, and prowess—all challenging areas for me. But humans have an inexplicable yearning to connect with the natural world, and this magnetic pull is even more important and healing for disabled folks. We are less likely to have access to and live near green spaces than able-bodied people, which poses a barrier to reaping the benefits that green spaces offer, such as better mental health, opportunities for socializing, and lower stress.

Even the days when I merely set foot in the woods and am surrounded by greenery are some of my most heartening. I get vitamin D, time free from electronic devices, and sanctuary in the heart of forests. Once I was introduced to wild edible plants and fungi, I began to see them everywhere. But before I could forage them, I needed to learn how to accommodate my physical disabilities.

This magnetic pull is even more important and healing for disabled folks.

My day-to-day cane, for instance, works fine on paved concrete. But because fungi thrive and spread their spores in dampness, the hours after a fresh rain are when it all happens for a mushroom forager—and when the ground is particularly spongy. After multiple frustrating trips in which my cane sank and stuck in the earth, I hunted through online forums for a solution: a wide, flat pad attachment that provides more surface area. It’s foldable and easily tucked away when I’m back on pavement. It’s also useful for knocking down pesky gilled mushrooms that hang just a bit too far out of reach. I usually find some of the best, non-wormy oyster mushrooms and chicken of the woods sitting tantalizingly high up on deciduous trees.

A casual Sunday spent exploring the many vintage shops in Providence, Rhode Island, two years ago also resulted in the find of a lifetime: a rare canne-panier à champignons—a traditional French foraging cane with a wicker basket specifically intended for collecting mushrooms—tucked in a dusty corner among various knickknacks. Initially created in France for harvesting or even berry picking, these cannes became popular for gathering wild morels and chanterelles. These days, they are used mostly for decor and often encountered only in the depths of antique stores. But now I fold my everyday cane away and plunge the canne deeply into the soil, using its metallic spiked tip for leverage while pulling my prizes out of trees or the ground. It’s a bit gimmicky and doesn’t always fulfill the role of a walking stick, but using it satisfies my cottagecore desires.

Before I set out on a foraging trip, I pack sparingly: my Opinel pocketknife for neatly slicing mushroom stems, a phone for taking pictures and identifying specimens, a toothbrush to brush dirt off my precious findings, a light mesh bag for collecting, a water bottle, and a handful of snacks like granola bars and dried fruit. A light pack is key to preventing overexertion, particularly on trips where I spend three to four hours in the woods. I’ve also had to come to terms with the fact that I simply can’t move as quickly or for as long as most foragers, so I time 15-minute increments to make sure I stop to check in mindfully and see if I need a break. Many hikers are familiar with AllTrails, an app I use to track my route through new wildernesses and plan my trip extensively in advance. I thoroughly check feedback and difficulty levels to find trails where the ground is flat and shaded.

Here comes the prerequisite warning to never eat a mushroom you are unsure of. There’s a common saying among foragers: “All mushrooms are edible, some only once.” In other words, never eat a mushroom you are unsure of. That being said, I have plenty of experience identifying reishi and chaga, which have been used in traditional Chinese medicine for centuries, in the Catskills and woods of Rhode Island. I’ve used my findings to make tinctures and teas that help with inflammation from my chronic pain. They’re not replacements for medicine, but they provide additional relief.

These days, when I have the chance, I trek up from my home in Bed-Stuy in Brooklyn to Putnam Valley or the Big Indian Wilderness in the Hudson Valley and the Catskills; Central Park and the limited green space in the city simply don’t do it for me. And because there are always days when I am low on spoons and have limited energy or capacity to do daily tasks, I stay home and tend to my mushroom block from a Mushroom Queens grow kit. Right now, I’m hyperfixated on golden oysters.

There’s a common saying among foragers: “All mushrooms are edible, some only once.”

I fell in love with mushrooms because they align so clearly with disability justice. Disabled folks exist outside of what society considers “normal,” and mushrooms are just the same—thriving through nonconformity. Some boletes turn blue when sliced open. Many species have thousands of different sexes. And, through their constant renewal processes breaking down dead matter, they paradoxically symbolize both life and death.

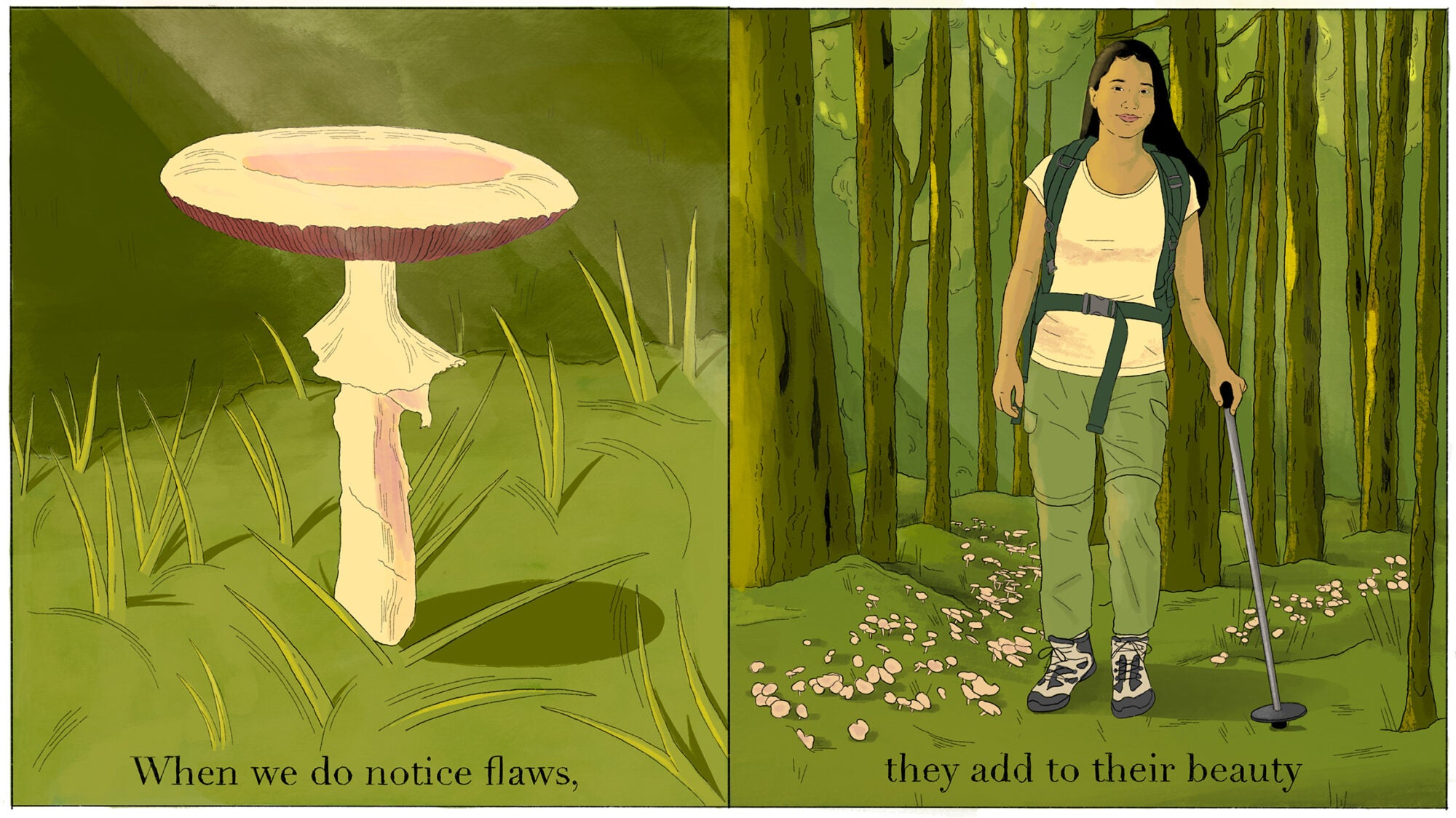

Some disabled foragers, like Jessica Lin, who urban forages for native plants in LA, and Fiona Bird, who scours beaches for seaweed in the UK, are working to make the experience more accessible. Lin says disability is visible everywhere, in both humans and nature. “When looking at any tree, flower, or mushroom, we admire it in its wholeness and rarely think about imperfections,” says Lin. “Even when we do notice flaws, they add to their beauty.” Foraging teaches us that we should look at ourselves and others in this way too—moving away from calling ourselves deficient and toward accepting what is working well and perhaps even beautiful.

Lin supplies transcripts of their workshops, sensory descriptions for color-blind individuals via touch and scent, and space for somatic expression for neurodivergent folks, like using fidget toys and plenty of space for wandering and interacting with others. They also run two-hour-long forages, just enough time to peruse without rushing. This is key, because foraging is so capricious—dependent on cloudiness, rain, time of day, and wind—that many treat it like a race when conditions are right. But Lin’s forages are a leisurely two hours, offering a reminder to take it slow. Many mushrooms are freckling the woods, just waiting to be unearthed, and there’s plenty of time.