Naoto Nakamura gave nearly 200 tours a year at the mythic Tokyo fish market. And now that it’s gone, he reflects on his time sneaking visitors through the twists and turns.

It was roughly 4 in the morning at Tsukiji Market in Tokyo, the largest and most famous fish market in the world, and the sticky August heat of 2017 was already intensifying as my wife and I stood in the shadow of a large delivery truck bathed in the glow of overhead floodlights. From the slippery, saline-scented darkness, Naoto Nakamura pointed toward a distant warehouse. Go straight, he told us, and walk briskly. Yes, we could take photos. No, he wouldn’t be walking with us; he’d meet us on the other side. And make sure not to wander into the path of the forklifts zipping around like minnows.

Naoto couldn’t walk with us, he explained later, because the security guards in this section knew what he looked like. He wasn’t really supposed to be there. We definitely weren’t supposed to be there. But while he’d be spotted and the game would be up, we’d be left alone, he told us, assuming we didn’t cause any trouble.

This was why we’d hired Naoto at the recommendation of a friend who’d gone on his tour some years before. He could get you into the places nobody else could. The apartment-sized walk-in freezer where men walked silently, pencils and notepads in hand, evaluating trays of uni stacked up like gold bars in a vault. The warehouse floor where man-sized bluefin tuna were quartered and sliced by literal swords. The administrative building—a repurposed train station—where clerical workers helped facilitate the import/export of an infinite selection of seafood.

Now, it’s over. Tsukiji Market, as it was, no longer exists. It closed on October 6, and demolition officially began soon after, to make way for the most pedestrian of eminent domain insults: a parking lot for visitors to the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo. Yes, the outer market is still there, and you can still eat sushi and buy trinkets from the remaining tourist-friendly vendors. Certainly the neighborhood of Tsukiji (which the market was named after) remains, although it’s unclear how it will fare now that its main attraction is gone. And yes, a new market called Toyosu, in a different neighborhood, has replaced it. But Tsukiji is gone, and in a sad way, so is the magic.

Tsukiji was legendary. An aquatic-life trading depot that restaurants were proud to say was the origin of their ingredients. To visit, and to be guided through the twisting labyrinth of the inner market, was to feel like a very small fish swimming in a very large, deep, and dark pool. Naoto was a guide to that mysterious abyss, and I’m not sure you’d be able to find anyone more dedicated to it, or who fought harder to save it.

In the year since our tour, we’d stayed in touch on Facebook, where he’d been chronicling his visits to city government offices to file protests and petitions, news of the coming shutdown, and, ultimately, a mournful op-ed he wrote in a local paper about the market’s impending closure. He is an expert in the dissolution of a thing he loved.

For four years, from 1978 to 1982, Naoto worked as a fish trader in the inner market of Tsukiji, and then spent eight more years in the industry performing jobs like processing salmon roe on a barge, working on Russian factory ships, and selling fish in supermarkets.

His time in the market left an lasting impression on him. In the mid-’90s, he wrote a book, To Be a Good Fish Dealer in Japan: Or, Such a Pity for the Fish, detailing what it was like to work in Tsukiji and in the fishing industry. He later wrote a second book, Free Jazz at Tsukiji Market, a compilation of essays about the market, his travels, and his relationship to the fishing industry.

Naoto is unsparing in his self-assessment. “I am a writer, but I am almost nobody,” he writes in an early chapter, as if his stories of traveling to places like Alaska and Russia, or of the time he learned that a memorable, disrespectful customer was actually a Filipino mob boss doing research for a lobster-related Ponzi scheme, count for nothing.

“Those days there was absolutely no kind of key word like ‘Tsukiji’ on the Internet,” he says when I call him to ask about how his touring business first got started. “When anybody put ‘Tsukiji’ into the Internet the only site they would hit was me, so I was always at the top.”

He estimates that he took at least 200 tourists a year through the twists and turns of Tsukiji’s inner market. While he can’t be certain he was the very first person to put Tsukiji into Google’s algorithm, he’s confident he was the first to give tours, something the market itself didn’t organize.

“When the restrictions of Tsukiji Market started, it was because too many tourists gathered to the tuna auction sites,” he recalls. Eventually Tsukiji offered tickets to the auction, but there was no mechanism for nontraders to see the more intricate workings of the inner market, where the fish vendors operated. Technically the inner market was open to the public, but in practice if you were spotted by security you’d likely be escorted out (which was how our own tour ended, at the gentle but firm hands of several security guards).

At least to me, this is how the closing of Tsukiji Market feels: someone politely but unequivocally telling you that your time in a place that was wild and forbidden and strangely beautiful has come to an end. What it’s like for the people of Tokyo, and all of Japan, is still to be determined.

“I think it’s going to be very, very quiet from now on,” Naoto says sadly. “A kind of situation like a ghost town at Tsukiji Market. Many businesses will lose their motivations, or what they stood for. They can’t say, ‘I got this fish right from Tsukiji market this morning, so it’s very fresh.’”

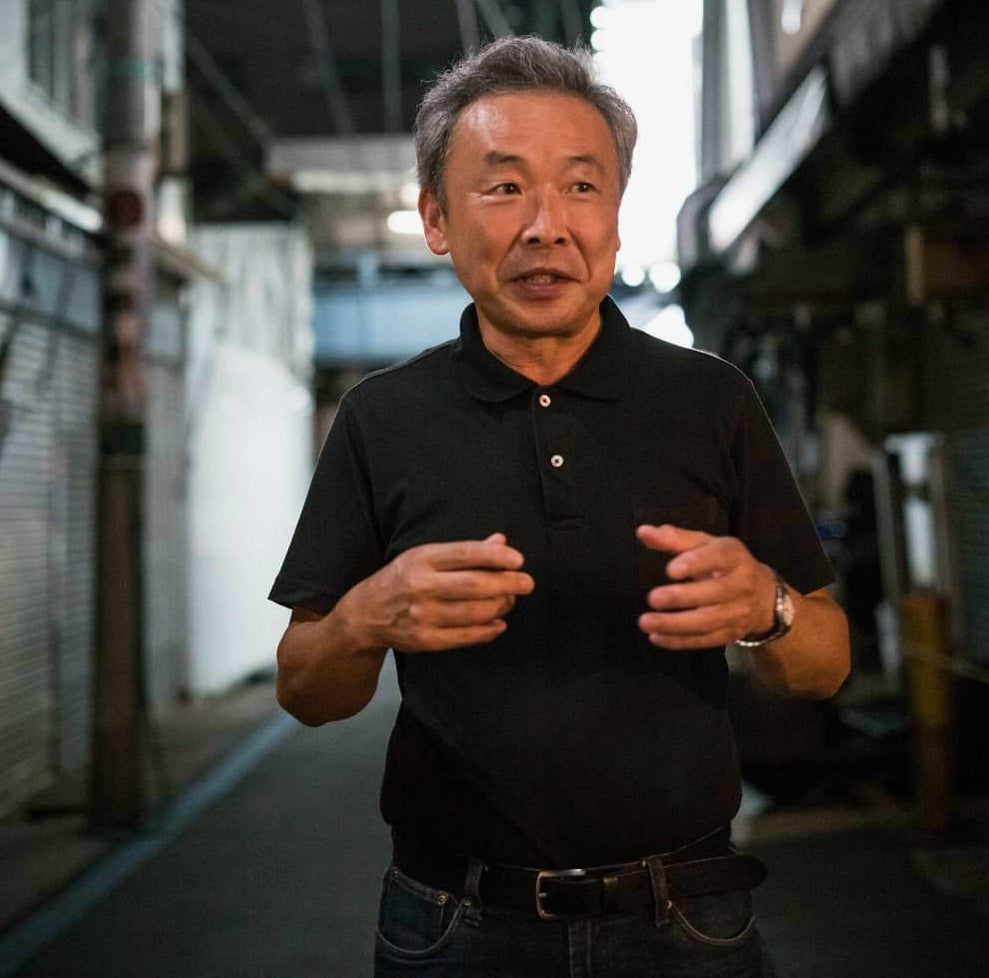

Naoto Nakamura portrait by Tham Kok Leong