The stars aligned in Hollywood when République opened. Now, with a new cookbook and a global empire, Marge Manzke is ready for the spotlight.

The sign of good brioche dough—the sweet, yeasty base for loaves, buns, or cinnamon rolls—is that it can pass something called the windowpane test: A baker will pull at the kneaded mass to create a small, tissue-paper-thin “window.” If the buttery dough tears too easily, it wasn’t kneaded properly, or the ingredients are the wrong temperature, or the ratio of fat is off. Brioche is so delicate and soft that it’s easy to forget it starts out as a strong, resilient dough.

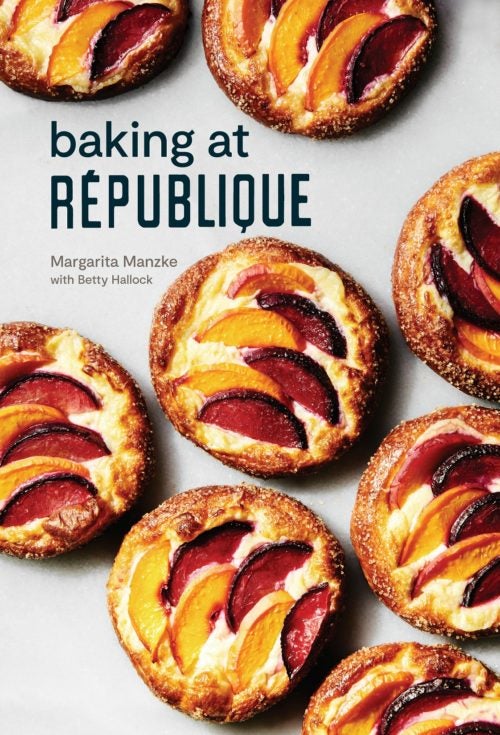

In her new book, written with Betty Hallock, Baking at République, the Los Angeles–based chef Marge Manzke admits that her favorite thing to make is “anything with dough, but especially bread, and particularly brioche.” For the past five years, Manzke has been churning out a staggering array of pastries and breads—both savory and sweet—at République, the all-day café and restaurant that she co-owns and runs with her husband, chef Walter Manzke. Brioche dough takes many forms on the menu and in the pastry case, from a brioche French toast as fat as a romance novel to a sticky “bomb” with maple, brown sugar, and pecans to bombolini stuffed with jam or custard. The book’s cover shot features one of Manzke’s signatures: fruit Danish, in which slices of peaches and plums are layered atop a vanilla custard nestled in soft, round pillows of brioche.

Every day at 8 a.m., Manzke’s team of 10 pastry cooks fill the restaurant’s nearly 15-foot-long pastry case with hundreds of items.

République, which is centrally located in L.A.’s mid-city neighborhood, about 10 miles east of the beach and six miles west of downtown’s flourishing dining district, has made an appearance on all of the city’s best-of lists since it opened in 2013. For dinner, it’s a full-service restaurant, with a full bar and a menu—with standards like iced oysters, eclairs stuffed with duck liver mousse, spinach cavatelli with morels and porcini, a rotisserie chicken with green garlic aioli, and pork three ways: belly, chop, and sausage—overseen by Walter. But for most of the day, the space operates as a casual café, with counter service from morning until the late afternoon.

“Everything about this space is historic,” Manzke said recently over a morning staff meal of sopes and eggs. In 1928, Charlie Chaplin had the space built to be his office; it went through a few lives and landlords until 1989, when it became Campanile, a landmark restaurant co-owned by chefs Nancy Silverton and Mark Peel. The same real estate housed Silverton’s original, groundbreaking La Brea Bakery until 2012. A year later, the Manzkes moved in.

Every day at 8 a.m., Manzke’s team of 10 pastry cooks fill the restaurant’s nearly 15-foot-long pastry case with hundreds of items. Fresh fruit tarts, glistening crème brûlée beignets, pillowy cheesecakes, crumble-topped pies, mochi loaves, savory scones, individual galettes, crusty loaves of bread, and piles of cookies draw a line of locals and tourists every day.

“We like to make it look really full every morning,” Manzke says. “So we start the day before, and we bake almost through the night.” Manzke’s bread and pastry offerings, each of which happens to be photogenic, are also technically very good. They demonstrate a deep knowledge that, because of the fast pace of food trends and power of social media hype, is becoming rare and is certainly underappreciated.

Manzke, born Margarita Lorenzana in Manila, got her first job at the age of seven. “When I wasn’t in school, I used to serve people behind the counter at my mom’s tiny, tiny restaurant, Turo Turo.” While her parents were busy running the family’s resort on the coast, Manzke would be “spooning stews or meats over rice into to-go plates,” Manzke recalls. “My sister would be behind the cash register. Now, thinking back, I wonder what the people coming in must have thought, seeing these two little kids serving them lunch!” Manzke and her siblings would also help out at her aunt’s catering company, building croquembouches, those conical towers of cream puffs. “We used to climb onto stools to reach the top,” Manzke says. She later went to college in Manila, but after her sophomore year, her parents decided to send her abroad.

Manzke and her sister enrolled at London’s Le Cordon Bleu, where they majored in culinary arts. Together, they went on to study at the Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, New York. Before she graduated, Manzke applied to do an externship at Spago, chef Wolfgang Puck’s popular see-and-be-seen restaurant. After graduation, Puck offered her a job. “I had become one of those people who believed New York City was the best city ever. I wanted to move there and live there,” Manzke says. “That was where I assumed I would work.” But when her sister returned to Manila, her brother—who was studying at UCLA at the time—invited her to live with him while she gave L.A., and Spago, a chance. It didn’t take long for Manzke to fall in love with the L.A. lifestyle, full of sunshine and bountiful farmers markets.

Despite the challenges of acquiring work visas and living far from home, Manzke kept landing at great, multistarred restaurants. From an externship at Spago, she moved on to Patina, chef Joachim Splichal’s highly rated fine-dining establishment, where she met Walter.

The management at Patina didn’t like it when the couple started dating. “They basically forced me out, and that’s how they handled that,” she says. She soon left for a job at Melisse, chef Josiah Citrin’s fine-dining spot just blocks from the ocean in Santa Monica. She rose through the ranks quickly to become one of Citrin’s sous chefs.

Eventually, after marrying, the Manzkes started consulting on restaurant projects together. Their first big splash was in 2007, when they opened Bastide. The serious but casual French-inflected bistro in West Hollywood was owned and financed by the notoriously mercurial Hollywood music video director Joe Pytka. After two years—and a three-star Los Angeles Times review—the Manzkes were out. When Walter took a job as the chef of a new brasserie called Church & State, in a then-unknown part of town called the Arts District, Marge developed the desserts. Local bloggers raved, but Manzke wasn’t all in.

“I wanted to take a step back. I made some tart recipes, and I even worked as a server, but I was thinking about starting a family then,” Manzke says. That’s when the idea of their own place, a sprawling, all-day concept, started to take shape—and when they had their son, Nico. Their daughter, Olivia, would follow a few years later. The Manzkes left Church & State in 2010 to focus on what would become Republique while consulting on projects in L.A. and Chicago.

At first, nothing went according to plan. After putting their life savings down to hold a massive, warehouse-like space in downtown L.A., building permits and contractors fell through. “We lost thousands and thousands of dollars,” Manzke says. In those days, the Manzkes were hopping between consulting gigs, hosting investor dinners, doing pop-ups, and driving their beat-up hatchback to ticketed food festivals, towing crates of gougeres, roasted meats, portable ovens, and coolers into makeshift stalls to help draw crowds in for a good cause.

When, in 2012, Sprout Restaurant Group approached them with the space that used to house Campanile, the Manzkes toured it and pretty much signed the deal on the spot. “We walked in, and we knew immediately that the left side would be the kitchen and the right side would be the bakery,” Manzke says. “It all fell into place.”

République, named after the neighborhood in Paris, opened a year later while Manzke was still working on her bakery menu. “At the time, it was not very common to have a restaurant that was open all day,” Manzke says. Her opening pastry menu consisted of just eight items. “At first, no one came,” she says. “But we just kept going and kept hoping people would get it.” That first year, locals would wander into the empty restaurant at 9 or 10 in the morning, grab a coffee and maybe a chocolate croissant, and see Manzke and Nico, barely three years old, cracking eggs for brioche or pasta dough. “We started them young, just like my parents did with me!” Manzke says.

Weeks went by, and then months, and then “suddenly there was a line out the door,” Manzke says. It wasn’t long before the line to get into République at 8 a.m. was just as long as the line to get in at 8 p.m. Now, tour buses actually stop in front of the restaurant several times a week, in the mornings and afternoons, with guides that explain the drill: There’s an exterior window where one can order a quick croissant and coffee to-go, but for the full effect it’s worth lining up in front of the pastry case.

“The thing people don’t get, have never gotten, about Marge is that she’s not just a pastry chef.”

Manzke learned humility, alongside hard work, early on. “It wasn’t as if our parents had time to recognize, or praise, every little thing we did,” Manzke says. But that might be why she’s not known for tooting her own horn, and not better known among the country’s most lauded culinary professionals. It’s something that frustrates her husband. Though Manzke is the executive pastry chef at République, she also works on the savory side of the menu with Walter, suggesting edits or additions on dishes as new produce comes into season. But because she’s been doing pastries since she started working alongside Walter, she’s often pigeonholed as a pastry chef.

“The thing people don’t get, have never gotten, about Marge is that she’s not just a pastry chef,” Walter is fond of repeating, almost exasperated each time he has to explain this. “She can do every single station on the hotline, from fish to the grill to expediting, and she can bake. I can only really do savory. Marge can do it all.”

Marge blushes a little bit when her husband talks about her, but then she quietly beams. She might be low-key on the outside, but that masks a laser focus and outsized ambition. That ambition—and a family connection—took the Manzke brand international.

“We had this idea to do something with my family in Manila,” Manzke says, crediting her sister, Ana Marie Lorenzana de Ocampo, as the mastermind and co-operator of what is now a sprawling empire of 17 restaurants, cafés, and ice cream shops in the Philippines.

De Ocampo runs the day-to-day business of Wildflour Bakery + Cafe, part of a restaurant group that the Manzkes and de Ocampo own and operate across the Philippines. When asked how they run an international operation, Manzke laughs, credits her sister again, and says, “FaceTime!”

In 2015, Richard Pink, co-owner of L.A.’s famous Pink’s Hot Dogs and a regular at République, approached the Manzkes with an idea. “‘If you ever want to take Pink’s to Manila, we should talk,’ he said. Walter and I looked at each other and said, ‘Why not?’” Manzke says, laughing. Pink’s Hot Dogs opened in Manila in 2016.

A year after that, back in L.A., a personal dream of hers came true. “I used to always joke with Walter and say, ‘One day, I’m going to open a Filipino restaurant!’” And in classic Walter fashion, he encouraged it. Though she never wrote out a business plan, the idea for a small place that served the food she grew up eating was always on Manzke’s mind. When a space owned by République’s management group opened up inside downtown L.A.’s Grand Central Market, Sari Sari Store was born.

In part modeled after Turo Turo, the shop Manzke ran for her mom as a kid, it’s a simple meat-over-rice operation. Jonathan Gold was an early fan, writing, “I have stopped by Sari Sari Store five times in the last three days, and I’m not sure if I should be admitting this to you or to a therapist…. I’ve given up my fidget spinner. I have Sari Sari Store instead.”

One of the items Gold couldn’t get enough of was Manzke’s buko pie. Similar to one her sister makes at Wildflour, Manzke’s buko pie recipe, which is in her cookbook, layers coconut pastry cream, coconut jam, and coconut whipped cream into a pie shell for a shock of sweet tropical flavors that’s earned a cult following on two coasts. “My sister’s is more famous, though,” Manzke says, always giving credit where it’s due, “because CNN interviewed her about it.”

Manzke and de Ocampo share recipes frequently and compare notes weekly. Another recipe that came over to the States from Manila is de Ocampo’s salted caramel chocolate layer cake. It’s a massive hit at République, but it’s the one signature République pastry recipe that’s not in her new cookbook. “I know people are not going to like that, but really, it’s my sister’s recipe. You have to ask her for it,” Manzke says.